You’re planning to write a story, but you don’t know whose point of view (POV) to tell it in. Author K.M. Weiland wrote a wonderful post on the subject, and I suggest you start there. I’ll wait here while you read that. The rest of my post supplements hers.

List the Contenders

Weiland’s 6-step process starts with identifying the contenders. You could choose any character in your story, or even select an omniscient, god-like POV.

Winnow Down the List

Next, Weiland suggests you think about which contenders matter least to the story’s drama. For example, a servant or guard who rarely speaks and whom you’ve only included for authenticity—a ‘spear carrier’ in literary lingo—makes a less useful POV character.

Rate the Stakes

In the next step, you consider each character’s stakes. What do they lose if they don’t get what they want? You’ll get more dramatic impact from characters with the most to lose.

What Type of Narration?

Choose from among first person (I/me), second person (you), third person (she/he), and omniscient (god-like). I’ve written about these before.

Pitch Your Tense

Most writers chose past or present. In past tense, she ran, she sat, she said. In present tense, she runs, she sits, she says. More stories use past tense, but you may choose either one.

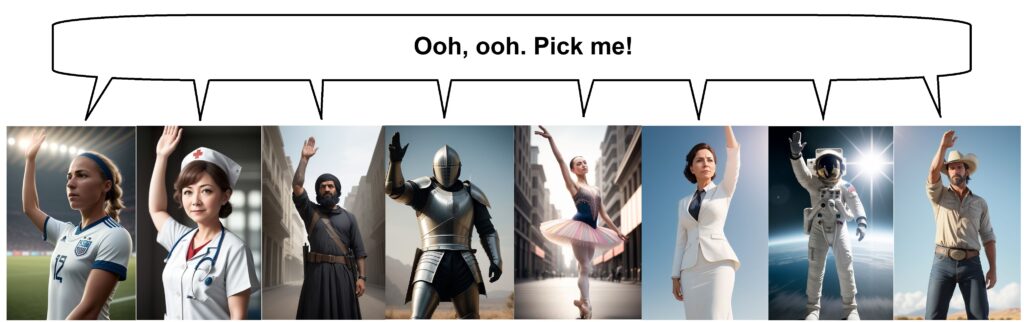

Final Auditions

After going through the above steps, you might still face a choice between more than one possible POV character. Weiland suggests you write a few paragraphs of the story in each of the remaining contenders’ POVs. They don’t know it, but they’re auditioning for the POV role. Choose the one with the most interesting voice, the one who tells your story best.

One More Consideration

The post by K.M. Weiland addresses all the above points better than I have, but I’ll add another thought. Nothing limits you to one POV for an entire story (though in flash fiction, you should restrict yourself to one).

You might choose a different POV for each chapter, or even each scene. As you do so, use the same six-step process mentioned above in selecting the appropriate character.

Also, make transitions between POV characters clear to the reader. In the first sentence of a section with a new POV character, include a thought, or a feeling, or both, from that character. That alerts the reader about the POV shift.

Of course, throughout the literary world, experts agree the very best point of view is that of—

Poseidon’s Scribe