If you write genre fiction, you write for two sectors of the reading public. Problem is, they want opposite things. What do you do?

For any genre—and I’ll use science fiction as my example—you’ll have two types of readers. Let’s call them Experts and Newbies. You’d like both of them to buy and enjoy your books.

Experts

The first type knows the genre well. Scifi experts can quote the Three Laws of Robotics, have a ball lecturing you about Dyson Spheres, reveal the universal question for which the answer is 42, and babble on about Babylon 5. They read often, and crave the most recently published stories, and prefer them crammed with all the technologies and the latest scientific discoveries.

Newbies

Don’t take that term the wrong way. We all start as newbies. The newbie takes a chance when buying your book. Despite harboring doubts about scifi, the newbie remains curious and willing to learn. The newbie may not know a warp drive from a hard drive, but likes a good story as long as it doesn’t confuse.

These two types differ in their approach to what I’ll call New Stuff and Tropes.

New Stuff

I mentioned experts seek technology and scientific discoveries. They want the latest, the cutting-edge, the most imaginative concepts. Give them the New Stuff. Not only that, they want the full explanation. What’s it look like? How is it powered? How fast does it go? What languages can it speak? You could write many pages of convincing technobabble without boring an expert.

Newbies don’t delight in New Stuff. It’s all new to them. They just want to know how the characters feel about the new stuff and how it affects the plot. Any paragraph that reads like a technical manual annoys them, maybe enough to stop reading.

Tropes

With tropes, the situation reverses. Here, I using the term to refer to technology or concepts well known to readers of the genre. Expert readers get your meaning as soon as you mention wormholes, the multiverse, generation ships, FTL, or cryosleep. If you go further to explain the trope, experts feel insulted.

Newbies, by contrast, get stumped by tropes. These strange words and phrases serve as an ejection seat to launch them out of the story. Just a brief definition would save newbies from frustration.

The Balance

As a writer, you’d like to please both types. When it comes to New Stuff, you should aim for just enough explanation to satisfy experts, but not so much that it bores newbies. With Tropes, seek the briefest definition to help out the newbies. Better yet, define the term in context so newbies can catch the meaning and experts don’t get exasperated.

At a critique group meeting recently, one member criticized my manuscript, saying I hadn’t defined an unfamiliar term, but that member managed to glean what it meant. Another group member knew the term, and said I shouldn’t bog down the prose with further explanations.

I’d achieved balance.

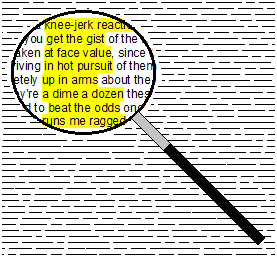

The Signal Technique

Say you’ve got some new stuff in your story. You want to explain it all for the benefit of experts without making newbies nod off. Perhaps the signal technique will work. At the beginning of a paragraph, provide a signal to the reader that a long description follows. If you make the signal clear enough, the expert reads on with eagerness and the newbie skims or even skips that part.

This method might work as well for tropes. Here the signal tells experts they may skip an upcoming explanation without missing anything, while the newbies should read the paragraph to understand the unfamiliar jargon.

Jules Verne mastered that technique. Known for including long lists, he provided unmistakable signals in advance. It’s as if a hypertext alert pops up from the page saying, “Uninterested readers may skip this next part.”

Summary

Needless to say, I’ve simplified things in this discussion of two audiences. Your readers span a spectrum from newbie to expert and all points in between. You can write for them all if you keep their preferences in mind. Maybe, for your next book, one member of your reading audience might be—

Poseidon’s Scribe