Ever notice how fiction seems full of conflict? Characters hate each other, fight each other, struggle with problems, strive to survive, etc. Why can’t they just get along together and have nice, trouble-free lives? After all, that’s what we real people want for ourselves, right?

Necessity

You may go ahead and write stories where nothing bad happens, where characters are always kind and thrive in a stress-free environment.

Just one little problem with that notion…no one is going to read those stories. They’d be boring! There is no reason to care about such characters. Their outcome is not in doubt.

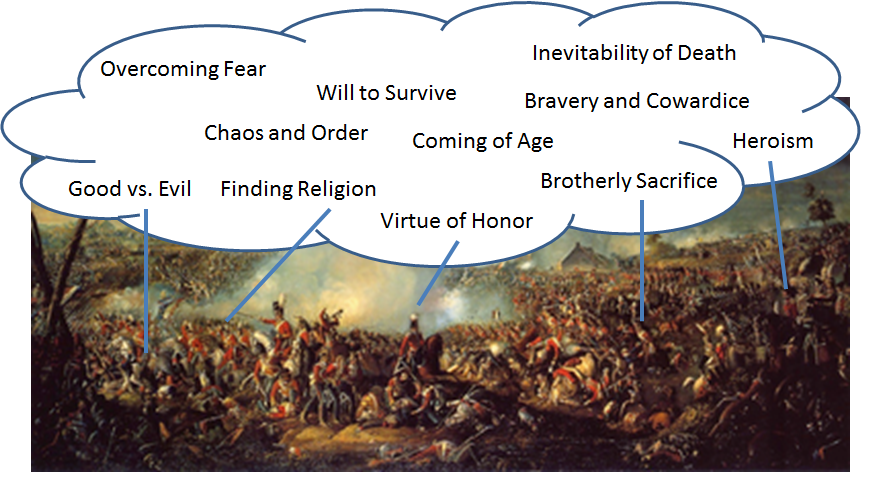

Conflict is, therefore, an essential aspect of all fiction. Conflict drives the plot and creates interest in the characters. Since all fiction is about the human condition, and since conflict is inherent in the human condition, your stories had better include some type of conflict.

Conflict is, therefore, an essential aspect of all fiction. Conflict drives the plot and creates interest in the characters. Since all fiction is about the human condition, and since conflict is inherent in the human condition, your stories had better include some type of conflict.

You might be objecting as you think about great stories you’ve read that didn’t involve any guns, bombs, swords, spears, knifes, or fistfights. Ah, but think deeper about those stories. Did characters disagree verbally? Did a character struggle to survive against Nature’s fury? Was a character conflicted internally?

Conflict comes in various kinds and need not involve violence at all. At its essence, conflict is two forces in opposition to each other. That’s it.

Types

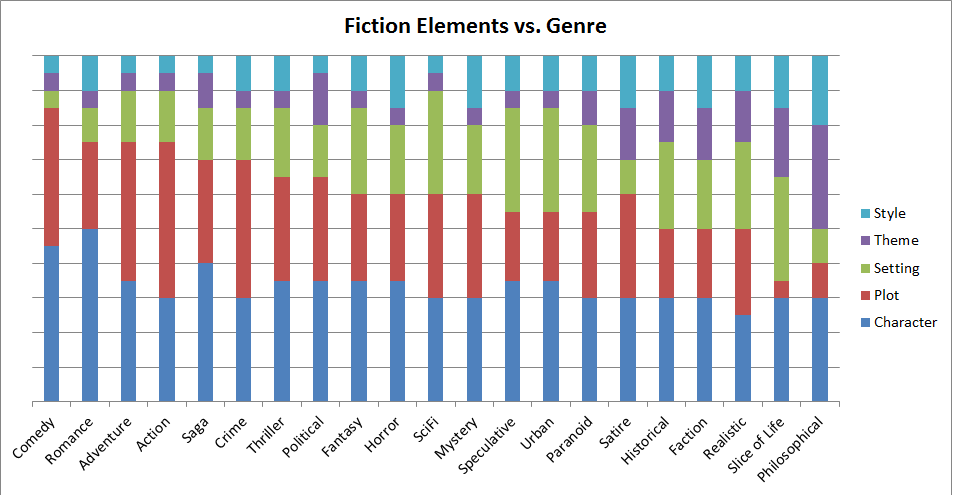

What are the types or categories of conflict? Here’s my classification schema:

- External

- Character vs. Character

- Character vs. Nature

- Character vs. Society

- Internal

- Character vs. Self

Some people add other external conflict types such as Character vs. Technology, Supernatural forces, Fate, or others. To me, those are all included in the basic four types.

How many types of conflict should you include within a single story? Unless it’s flash fiction, I recommend at least two, with one of them being an internal conflict. We live in a psychological age, and readers want to see characters with some depth, some internal struggles, some flaws. Readers don’t even want antagonists to be pure evil; there needs to be some explanation how they turned so bad.

Resolution

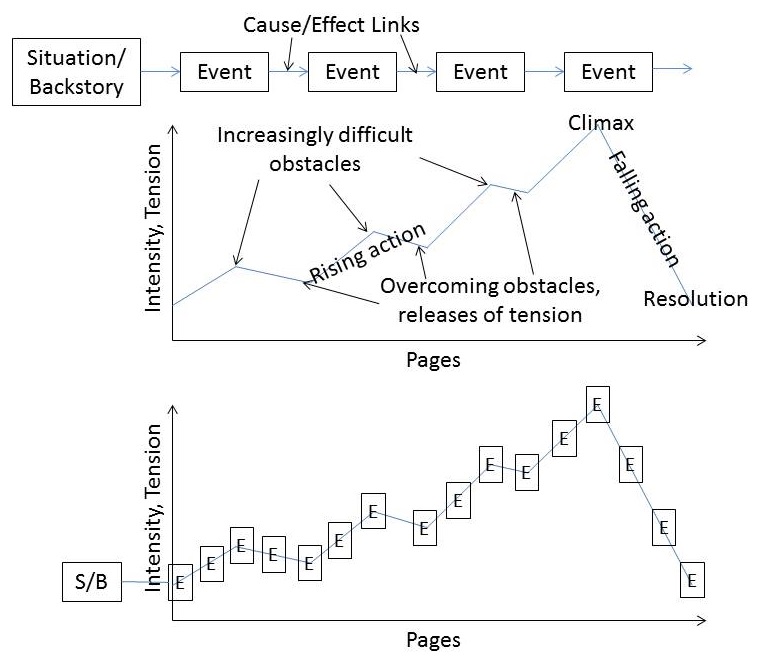

I’ve blogged before about the need to ramp up the level of conflict in your story, but what about the resolution of the conflict at the end?

Although I personally enjoy stories where protagonists overcome their adversity through wit, cunning, and intelligence, it need not be that way. Not all conflicts need to be completely resolved at the end. Or the resolution of one major conflict may spark the start of another. Really, the struggle during the bulk of the story is more important than the resolution.

In fact, the protagonist may lose the struggle, as in Jack London’s famous short story, “To Build a Fire.” That story illustrates that fiction really is about characters contending with difficulties, not necessarily overcoming them in the end. It truly is about the journey, not the destination.

Resources and Summary

There really are some nice blog posts about conflict out there, including this, this, this, this, and this.

Those are my opinions about conflict. You might disagree, and that disagreement itself would represent a type of conflict between you and—

Poseidon’s Scribe

experience is based solely on twenty years of being in small, amateur, face-to-face critique groups; not writing workshops, classes, or online critique groups; so the following advice is tuned to that sort of critique.

experience is based solely on twenty years of being in small, amateur, face-to-face critique groups; not writing workshops, classes, or online critique groups; so the following advice is tuned to that sort of critique.