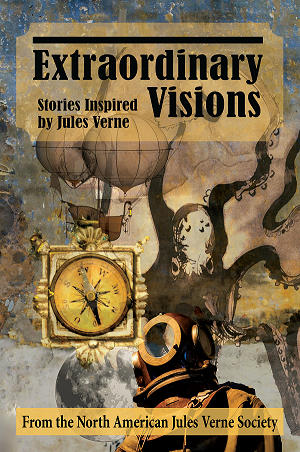

The anthology Extraordinary Visions: Stories Inspired by Jules Verne brought together authors of varied backgrounds and interests. Today I present an interview with Joel Allegretti, but—as you’ll find out—he writes in many formats beyond the short story form.

Joel Allegretti is the author of, most recently, Platypus (NYQ Books, 2017), a collection of poems, prose, and performance texts, and Our Dolphin (Thrice Publishing, 2016), a novella. His second book of poems, Father Silicon (The Poet’s Press, 2006), was selected by The Kansas City Star as one of 100 Noteworthy Books of 2006.

He is the editor of Rabbit Ears: TV Poems (NYQ Books, 2015). The Boston Globe called Rabbit Ears “cleverly edited” and “a smart exploration of the many, many meanings of TV.” Rain Taxi said, “With its diversity of content and poetic form, Rabbit Ears feels more rich and eclectic than any other poetry anthology on the market.”

Allegretti has published his poems in The New York Quarterly, Barrow Street, Smartish Pace, PANK, and many other national journals, as well as in journals published in Canada, the United Kingdom, Belgium, and India.

His short stories have appeared in The MacGuffin, The Adroit Journal, and Pennsylvania Literary Journal, among others. His musical compositions have appeared in Maintenant: A Journal of Contemporary Dada Writing & Art and in anthologies from great weather for MEDIA and Thrice Publishing. His performance texts and theater pieces have been staged at La MaMa, Medicine Show Theatre, the Cornelia Street Café, and the Sidewalk Café, all in New York.

Allegretti is represented in more than thirty anthologies. He supplied the texts for three song cycles by the late Frank Ezra Levy, whose recorded work is available in the Naxos American Classics series.

Allegretti is a member of the Academy of American Poets and ASCAP.

Let’s get to the interview:

Poseidon’s Scribe: How did you get started writing? What prompted you?

Joel Allegretti: When I was in the fifth or sixth grade, I said to my father one day, “I want to write a book.” He thought it was a good idea.

I was a fan of Greek and Roman mythology in my younger years. I wrote a little story called “The Flaming Sword.” I think it took place in Roman times. It was about a soldier who had a sword encased in fire, but that’s all I remember. I cut up pieces of paper, stapled them into a booklet, and wrote and illustrated my story.

I wonder if I created an ancient-world prototype of the Jedi lightsaber.

P.S.: Who are some of your influences? What are a few of your favorite books?

J.A.: My earliest influences were Jules Verne and Edgar Allan Poe. Then came Ray Bradbury, Leonard Cohen, Gabriel García Márquez, and Jorge Luis Borges. A big influence on my short stories isn’t a literary figure, though, but a TV series: The Twilight Zone, the original series hosted by Rod Serling, whom I still admire. I like to conclude a short story with a surprise ending. The Twilight Zone is all about surprise endings.

A few favorite books are Selected Poems: 1956 – 1968 by Leonard Cohen; One Hundred Years of Solitude by García Márquez; The Phantom of the Opera by Gaston Leroux; Immortal Poems of the English Language, edited by Oscar Williams; The Voice That Is Great Within Us: American Poetry of the 20th Century, edited by Hayden Curruth;and Our Lady of the Flowers by Jean Genet, translated by Bernard Frechtman. I find myself re-reading The Time Machine by H.G. Wells every few years. Ditto Jean Genet in Tangier by Mohamed Choukri, translated by Paul Bowles.

One Hundred Years of Solitude had a monumental impact on my reading tastes for a few years. It opened me up not only to the author’s others works, but to the rich world of Latin American literature as a whole. Unfortunately, I don’t know Spanish or, in the case of Brazilian writers, Portuguese, so I had to read the books in English translation.

On the Road by Jack Kerouac affected me when I read it at nineteen. The closing paragraph influenced the last stanza of a poem I published five years ago, “The Day after the Night John Lennon Died.”

I was captivated by Jack London’s Martin Eden when I read it in the ‘80s and dove into other London works, both famous ones, like The Call of the Wild, and lesser-known ones, like Before Adam. In 1990 I traveled to San Francisco for work and made a special trip to Jack London’s Wolf House in Glen Ellen.

It was also in the ‘80s that I discovered Graham Greene and W. Somerset Maugham and read book after book after book by both writers. I go back to Maugham’s short story “Faith” from time to time.

P.S.: You’ve written poems, short stories, a novella, theater works, and musical compositions. Is there anything you can’t write?

J.A.: I think the full-length novel is beyond my natural abilities. My novella, Our Dolphin (Thrice Publishing, 2016), runs 19,000 words. It ran 46,000 words before I took an editorial flail to it. “This can go. This can go. This adds nothing.” Now, 46,000 words is a substantial word count for me, but it’s too short for the novel market, which generally requires a minimum word count of 65,000.

I remember talking on the phone with a late poet friend over a dozen years ago. She told me she was writing a prose book and had written 800 pages. I said, “I wouldn’t know how to fill 800 pages.”

P.S.: You’ve stated that your novella, Our Dolphin, is an example of magic realism. What drew you to that style, and in what ways does your novella exemplify it?

J.A.: Magic realism influenced Our Dolphin. I wouldn’t have conceived it had I not read Latin American writers, but I can’t say it is magic realism.

The first part of the book takes place in a little Italian fishing village. The main character, Emilio Giovanni Canto, is the deformed adolescent son of a fisherman. One night he hears commotion coming from the beach and goes out to investigate. He discovers a small dolphin stranded on the shore. Emilio helps the creature back in the water. Emilio later meets it again and discovers it has the power of human speech, but only he can hear it.

Certain phrases in that part of the book, like “a gull of mythological proportions” and “the face that brought her infinite despair,” show the influence of García Márquez, or of García Márquez as translated into English by Gregory Rabassa (One Hundred Years of Solitude, Chronicle of a Death Foretold, et al.) and Edith Grossman (Love in the Time of Cholera).

Other literary influences are at play in Our Dolphin. The main character, Emilio, was inspired by my favorite literary character, Erik, whom everybody knows as the Phantom of the Opera.

The second part of the book takes place in Tangier. The scenes were influenced by the writings of Paul Bowles and William S. Burroughs, who’s my favorite Beat writer. In fact, one of the characters in Our Dolphin, a man known only as Moore (not his real name), is based on Burroughs. I took a day trip to the city in 1990 and drew on my memories when I was writing that section of the novella, but ultimately, the Tangier of Our Dolphin is a Tangier of my imagination.

P.S.: Though you’ve written many forms of poetry and prose, is there one or more common attributes that tie your written works together (genre, character types, settings, themes)?

J.A.: I like to investigate the ordinary in the out of the ordinary and the out of the ordinary in the ordinary.

P.S.: Your book Platypus (NYQ Books, 2017) contains poems, short stories, Fluxus-inspired instruction pieces, and text art. Does it defy categorization as much as a platypus does, or is there some common theme tying the parts together?

J.A.: Platypus has thematic sections, but as you point out, the book contains a little bit of everything, so I named it after an animal that has a little bit of everything.

P.S.: What are the easiest, and the most difficult, aspects of writing for you?

J.A.: The easiest aspect? Coming up with an idea. Ideas pop into my head all the time. though I don’t follow through on all of them. I’m always jotting down ideas and potential titles, as I guess most writers do. This goes for both prose and poetry, my primary genre.

The most difficult aspects? Bringing an idea to fruition and getting the work right. Here’s an example. I spent several hours a day for six days in a row revising a 5,200-word short story that had gone through multiple iterations and larger word counts. I wound up cutting it down to 4,700-plus words. Every time I thought I was done, I found something else I wanted to change. My instincts with respect to this particular story worked out in my favor. I submitted it to a magazine one morning and received an acceptance that evening. How often does that happen?

P.S.: The anthology you edited, Rabbit Ears: TV Poems (NYQ Books. 2015), includes a large number of poetic tributes to television. What or who inspired this idea, and would the book induce a reader to watch more TV, or turn it off forever?

J.A.: This is where my professional background comes in. I spent my career in the business world, specifically, in public relations. My last position before retirement was Director – Media Relations for a national not-for-profit financial-services organization. I prepared the CEO, the vice presidents, and other spokespeople for press interviews. I dealt with 60 Minutes, Nightly Business Report, and producers at local TV stations around the country. I was inside TV studios. I was well aware of television’s power.

Without that experience, I doubt an anthology of TV poetry would have occurred to me.

In 2012 I was reading Dear Prudence, the selected poems of David Trinidad. One of the poems is “The Ten Best Episodes of The Patty Duke Show.” My favorite sit-com from that time period is The Dick Van Dyke Show. I wrote a poem called “The Dick Van Dyke Show: The Unaired Episodes.” Here’s an excerpt: “1966. Sally’s boyfriend, Herman Glimscher, confesses to everyone that he and his mother are really husband and wife.”

A couple of months later I wrote a poem about Bob Crane, he of Hogan’s Heroes and seedy extracurricular activities. It occurred to me then that I hadn’t seen an anthology of poetry about a medium that had influenced our language, politics, and lifestyles.

Rabbit Ears is a celebration of TV. The 130 contributors reveal an abiding interest in and affection for the subjects they cover, from Rod Serling to Gilligan’s Island to the Emergency Broadcast System to the Miss America pageant to American Idol to Buffy the Vampire Slayer, etc., etc., etc.

Incidentally, Rabbit Ears serves a charitable function. All contributor royalties earned on sales go to City Harvest, a New York food-rescue organization.

P.S.: In what way is your fiction distinctive, different from that of other authors?

J.A.: I have to be careful how I answer this question lest I come across as unconvincingly humble or as somebody with an ego the size of Brooklyn. I’ll say my fiction is different from other authors’ fiction because I’m the one who writes it.

P.S.: I think every Jules Verne fan would love to attend the carnival you describe in “Gabriel at the Jules Verne Traveling Adventure Show,” your story in Extraordinary Visions. Where did you get the idea for that story?

J.A.: I certainly would enjoy a night at the Jules Verne Traveling Adventure Show.

When I saw the call for submissions on the North American Jules Verne Society website, I got excited, since I grew up reading Verne and watching films like Journey to the Center of the Earth, with James Mason and Pat Boone, on TV. I made it my personal mission to write a short story to submit.

The inspiration for “Gabriel at the Jules Verne Traveling Adventure Show” was Ray Bradbury’s novel Something Wicked This Way Comes, which I read when I was thirteen and again maybe fifteen years later. It’s about a demonic carnival that sets up shop in a small Illinois town. It gave me the idea for a World’s Fair-type of show featuring amazing Verne vehicles like the Nautilus, Robur the Conqueror’s Albatross, and the mechanical elephant in The Steam House.

I consider my status as a contributor to Extraordinary Visions to be an important accomplishment. I see myself as having come full circle.

P.S.: Since both the “Gabriel” story and Our Dolphin feature young boys, could you compare and contrast Gabriel Henderson and Emilio Canto, the respective protagonists?

J.A.: There’s some of me in Gabriel Henderson. I drew on my boyhood memories of reading Verne to create him. There’s a scene in which Gabriel goes to his local library to find books by Verne. Whenever I went to a library, I walked straight to the V section in Fiction. Gabriel, by the way, is my Confirmation name. It was also Verne’s middle name, but I didn’t know that when I chose it. I took the name of an Italian saint, St. Gabriel Possenti.

Emilio Canto, a deformed boy, is another matter entirely. The inspiration for him was purely literary: the Phantom of the Opera.

P.S.: What is your current work in progress? Would you mind telling us a little about it?

J.A.: I’m working on placing a short (41,100+ words) novel, Vera Peru, Euro-Siren of the ‘60s, a blend of pulp fiction and imaginary music biography. The inspiration for the title character was the Velvet Underground’s Nico, who has fascinated me for decades.

The novel opens in 1984 in New York’s East Village. A dissipated wreck of a middle-aged junkie from Alphabet City is arrested for shooting up her grandson with heroin. She gives Detective Dominic Andante her vital information: name, age, address, nationality (French). She says at one point, “It’s obvious you don’t know who I am. I’m Vera Peru. I’m an international celebrity.” She mentions being late for a recording session and having to face her producer’s wrath. Andante thinks she’s drug-crazy. He starts investigating and discovers she was telling the truth; she was an important person in France and England in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

For Detective Andante, Vera Peru’s offense isn’t just another heinous crime. It has a parallel to a decade-old tragedy in his personal life. As a result, he becomes obsessed with Peru and determined to learn what could have motivated this once-glamorous woman, who had achieved European stardom, to descend into narcotic degradation and commit such an unspeakable act on her own blood. But there’s more at play than even he, an experienced New York police detective, expected. As I write in the final chapter, “He hadn’t seen this.”

Vera Peru, Euro-Siren of the ‘60s comprises alternating chapters that cover Andante’s investigation and the title character’s life and career, from modeling in Paris to stardom in French cinema to hit singles in England to a disappointing entry into the American market and, finally, to her fall. There are cameo appearances by George Harrison, Allen Ginsberg, David Bowie, the Ramones, and Jean Genet.

As coincidence would have it, Jules Verne makes an appearance. During her acting career, Vera Peru works with a Greek-French director, who considers making a film of Verne’s novel about the Greek War of Independence, The Archipelago on Fire.

In addition, I completed a new poetry manuscript, Concrete Gehenna. The 60 poems cover a wide range of subjects, including classical, rock, and avant-garde music; film; the visual arts; New York City; members of the Warhol Factory; mortality; and religion.

The influences, likewise, are varied. Individual poems were inspired by, among others, Asian and Native-American forms, Edgar Allan Poe, Wallace Stevens, Weldon Kees, Frank O’Hara, Anne Carson, and Yoko Ono’s Fluxus-era instruction pieces.

Poseidon’s Scribe: What advice can you offer aspiring writers?

Joel Allegretti: Regard yourself as your primary competition. Look at what you’re writing now and compare it to what you’ve written. Are you writing the same work over and over? Are you absorbing new influences? Are you stretching yourself?

Moreover, I advise that you put effort into developing your own voice.

Poseidon’s Scribe: Thanks, Joel. You caused me to look up ‘Fluxus.’ Best of luck with the novel!

Readers can find out more about Joel Allegretti’s writing at his website, his Wikipedia entry, and his Amazon author page. You may also read his previous interviews here and here.