No matter how much a science fiction writer keeps up with science, the writer’s stories will go obsolete.

As science advances, our understanding of the universe changes. A spherical earth replaced a flat one. A sun-centered solar system replaced an earth-centered one. Birds replaced reptiles as closer descendants of dinosaurs. Continental drift replaced an unchanging map.

SF stories based on outdated science seem backward, passe, naïve. Yet we still read them. Why?

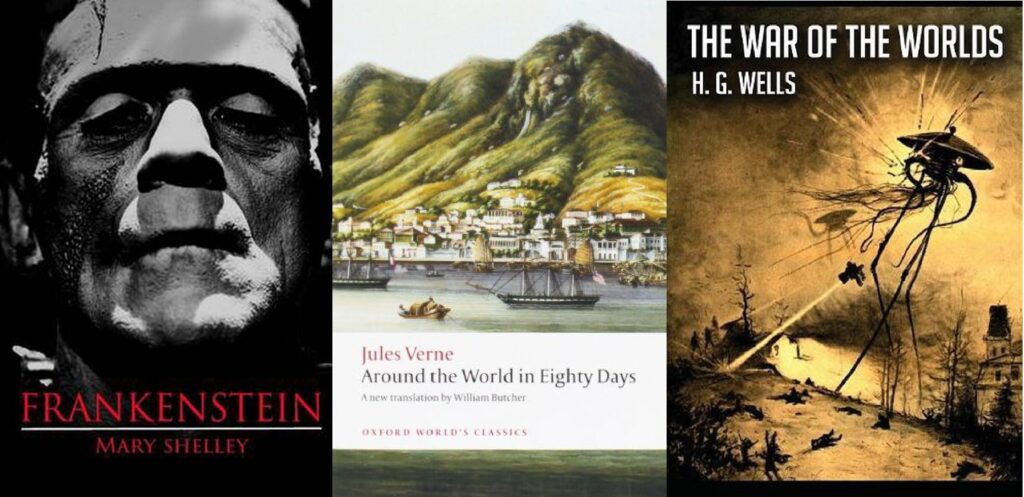

When Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, she may have thought the technology to animate dead human tissue lay in the near future since Luigi Galvani had caused frog legs to twitch with jolts of electricity. Two centuries later, we still can’t animate dead humans. How silly it seems to have ever thought it possible at the dawn of the 19th Century. Yet we still enjoy Shelley’s novel today.

Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days astounded his reading audience at such a short duration for a globe-circling trip. Today, astronauts orbit the planet in just over eighty minutes. How quaint to think of an eighty-day circumnavigation as short. Yet we still enjoy Verne’s novel today.

H.G. Wells’ story The War of the Worlds gave us invaders from Mars. Today we can’t imagine fearing an attack from inhabitants of that planet. How pathetic to think people once swallowed that premise. Yet we still enjoy Wells’ novel today.

Why do we readers find these outdated, naïve, obsolete books—and others like them—still readable? Because science fiction isn’t only about science.

SF, like all fiction, is about one thing—the human condition.

True, readers of SF prefer stories in which authors adhere to the science at the time of writing. But as decades pass, readers know the progress of science may render a work of fiction obsolete. They forgive all of that for the sake of a good story.

They want to read about human characters struggling to achieve a goal, to win a prize, to survive. To live means to suffer, but also to strive against and despite that suffering. The struggle reveals the human qualities of bravery, ingenuity, perseverance, loyalty, love, and others. These timeless truths persist no matter how much science morphs our understanding of the cosmos.

As essayist James Wallace Harris stated in this post, “It’s the story, stupid.” Author Michael Sapenoff put it this way: “So while the language itself remains outdated, the ideas are not.”

You may shake your head, chuckle, or even sneer at the obsolete notions in SF stories, ideas since debunked or overturned by later discoveries. But remember, while looking down your nose, science fiction is more about the fiction than the science.

I encourage you to suspend your scientific skepticism and just enjoy the tale, follow the spinning of the yarn. Set aside the transitory and obsolete parts and appreciate the unchanging, permanent parts.

Maybe, in the end, the SF obsolescence problem isn’t a problem after all, for you or for—

Poseidon’s Scribe