Listen up, you dull, lazy, unimaginative bores! I’ve got exactly one blog post to whip your sorry, uninspired butts into the most steely-eyed, creative writers who ever scribbled for this great country.

What’s that? Did I hear one of you say you’re just not creative? First of all, no talking in ranks. Second, you were creative once, back when you were three to five years old. You were uninhibited, freewheeling, and super-creative then. What happened to you? Get intimidated by a little criticism? Did adults often tell you that you were wrong? Did they tell you to stand or sit in neat, straight lines…?

Hmmm. Okay, new formation. I want you to sit, stand, or lie down facing in any direction you want. Still no talking, though. You will listen to everything I tell you. You will do everything I tell you, and you will become more creative. Do you understand? The proper response is ‘Yes, Drill Sergeant!’ I can’t hear you!

To allow for possible penetration into your feeble brains, I will keep these techniques simple. When faced with a writing problem, any writing problem, use these methods. They will work when you believe you can’t think of a story idea, create a compelling character, describe a setting, or get yourself out of a plot hole.

- Give me ten. No, not sit-ups. Write down ten ways to restate your problem. Sometimes seeing the question a different way helps in finding an answer.

- Give me twenty. No, not pushups. Write down twenty solutions to your problem. Do not stop until you get to twenty. Do not criticize your solutions, no matter how stupid they are. Remember, a stupid idea can inspire a good one.

- Move your lazy behind. I mean move Go for a run, or a walk. Your body and brain are one. Moving one will move the other.

- Go somewhere else. Move your rear end to a different place. A different room. Outside, maybe. Find a place that stimulates you, where you feel more creative.

- Doodle, or do focused doodling like the 30 Circle Test.

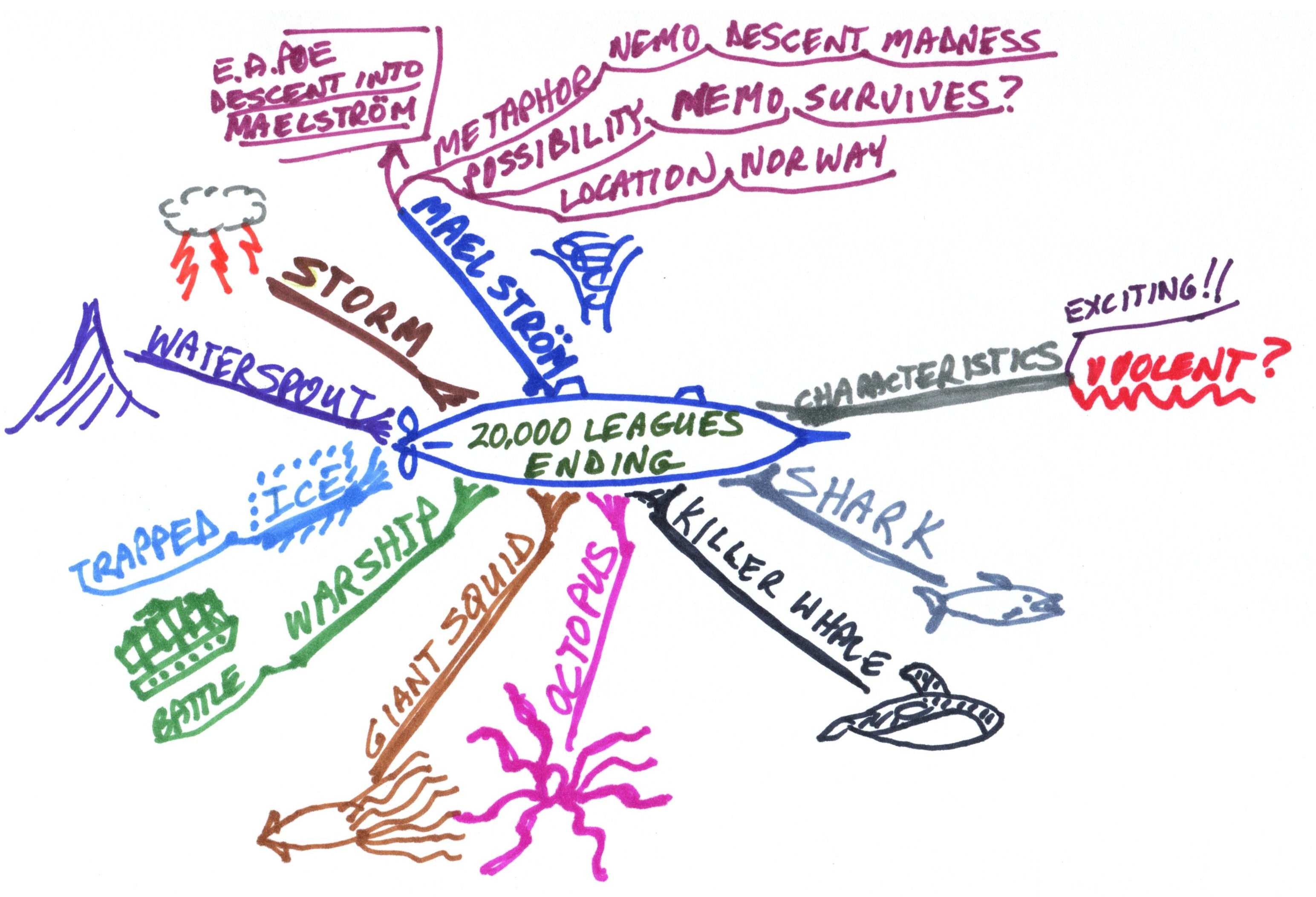

- Draw a mind map of your problem.

- Look at your problem from three perspectives. No, I can’t tell you which three without knowing your problem. It could be three characters, three physical directions, three time periods, or three other perspectives. You figure that out from the nature of your problem.

- Shut up. Literally. Go to a quiet place. No TV. No radio. No rug-rats. Quiet. Maybe you’ve been too distracted for the answer to come to you.

- Approach your problem using all your senses. You have five of them, most of you. Sight, smell, hearing, touch, and taste.

- Quit sitting on your hands and use them to build something. Build a model of your problem, with an Erector Set, Legos, modeling clay, Silly Putty, Play-Doh, or Tinkertoys. If you see your problem in a physical way and shape it with your hands, you may think of a solution.

- Listen to music. What? How should I know what kind of music will work for you? That’s for you to figure out.

- Get help. We leave no writer behind in this outfit. Ask other writers you know, or members of your critique group, if you have one. They may think of answers you haven’t thought of. Remember to help them when they ask, too.

Do not think I came up with these ideas by myself. I got them from experts. You will visit their websites and review the information there. See the postings by Larry Kim, Michael Michalko, Christine Kane, Christina DesMarais, and Dr. Jonathan Wai. Also this article on WikiHow, and this TED talk by Tim Brown.

These techniques I’ve attempted to impart into your mundane, unoriginal skulls will increase your creativity. They will make you a better writer. They will make you feared by your competitors. They will save your writing career. Memorize them and practice them.

Ten-hut! You’re dismissed. Get out there and be creative writers. Never forget what’s been taught to you by your Drill Sergeant—

Poseidon’s Scribe