Do you refuse to read books written by authors who’ve held offensive beliefs or committed objectionable acts? Are their books, however well written, tainted by the author’s extra-literary reputation?

Controversial Authors

Rather than provide a complete list, I’ll mention a few, having found several discussed on this Reddit post. My beloved Jules Verne held racist and antisemitic views. Knut Hamsun supported fascists and Nazis. Ezra Pound was a fascist, racist, and antisemite. H.P. Lovecraft was a racist and Nazi sympathizer. Ernest Hemingway was a bully, alcoholic, racist, and antisemite. Ayn Rand had an extramarital affair and opposed altruism and religion. Isaac Asimov groped women. Marion Zimmer Bradley may have abused her child and tolerated her husband’s child abuse. Alice Munro defended her husband’s alleged sexual abuse of their daughter. This article about that last revelation prompted me to think about this post’s topic.

3 Degrees of Bad

We could divide our reasons for hating authors into three categories.

- Those who held and stated abhorrent beliefs that don’t appear, or barely appear, in their fiction,

- Those who held and stated abhorrent beliefs that are obvious in their fiction, and

- Those who performed objectionable actions, whether they wrote about them or not.

Any of these might cause you to refrain from reading books by that author. On the other hand, you might forgive an author for any of these reasons and choose instead to enjoy their books for the literary value.

Noncontroversial Authors

The world includes plenty of books. You could avoid books by troublesome authors and just read works written by saints. However, you may find saintly authors in short supply. Every author is, or was, human, and therefore burdened with faults and failings, just like non-writers.

Even those not known for offensive actions often wrote about their private beliefs. Today, many authors use social media to express opinions on news of the day. Fiction writers spend a lot of time musing about the human condition. They’re bound to form and express strong opinions on various topics, and some of those stances might offend you. The contemporary author whose works you most cherish might get toppled off the pedestal you’ve erected, after a single tweet or post.

Different Places and Times

Although plenty of today’s authors have said or done questionable things, I only included deceased authors in my list above. When judging author behaviors and beliefs, remember that we’re all victims, to some extent, of the culture we live in or grew up in. In various past societies, racism, sexism, and antisemitism once prevailed as normal. Phrases and character types that readers of those times and places accepted with little notice cause us to cringe today.

Is it fair to judge a past author’s work by today’s standards? Sure. You can judge, by any criteria you want, whether you like a book or not. Is it fair to blame a past author for not living up to our modern sensibilities? No. The author could not predict how society would change.

Authors Aren’t Their Characters

Though some do, I urge you not to judge authors by their characters. Some authors excel at showing us convincing evil characters. As readers, we might wonder how the author can get inside a twisted mind so well, and we might suspect the author of sympathizing with the bad guy.

In his novel Next, Michael Crichton portrayed a character named Brad Gordon as a creepy pedophile. I felt myself transported into the sick mind of this perverted character. Though Crichton managed the description well, I would never accuse him of pedophilia.

Your Choice

They say you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, though many do. Is it fair to make your decision about what to read based on the author’s personal life or beliefs? Of course, but you might be denying yourself a pleasurable reading experience. What I’m saying is, you be you and I’ll be—

Poseidon’s Scribe

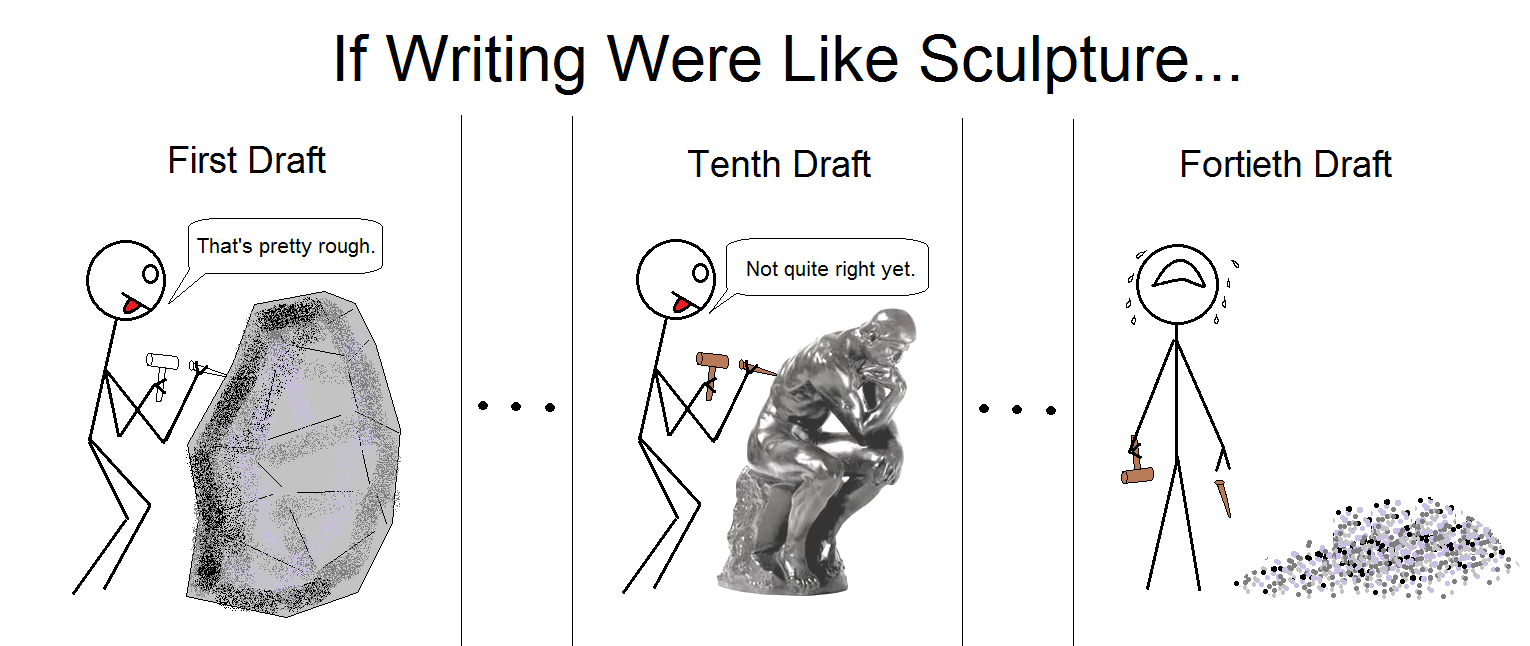

We could seek advice from accomplished authors. Unfortunately, the various quotes I’ve compiled run the gamut from the ‘don’t edit at all’ extreme to ‘seven revisions might not be enough.’

We could seek advice from accomplished authors. Unfortunately, the various quotes I’ve compiled run the gamut from the ‘don’t edit at all’ extreme to ‘seven revisions might not be enough.’