150 years have passed since the publication of Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, and we’ve been making the trip in blogpost form. Today, we’ve wound up in Medicine Bow, Wyoming. Phileas Fogg and his group have come 19,017 miles since leaving London on October 2, about 77.5% of the distance, but 82.5% of his time has elapsed, putting him in danger of losing his wager.

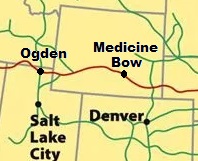

They left Ogden, Utah on the 5th and stopped at Fort Bridger in Wyoming Territory at 10:00am on the 6th. Early on the 7th, they stopped at Green River Station, where Princess Aouda saw Colonel Stamp Proctor riding the same train. Fogg had endured an altercation with Proctor back in San Francisco. At 11:00am, the train reached Bridger Pass, at the continental divide. By 12:30pm they passed in sight of Fort Halleck.

Not long after that, the train stopped. A signalman from Medicine Bow declared the bridge a mile ahead too weak to bear the train’s weight. The train’s engineer proposed to cross the bridge at high speed. Here, Verne portrayed Americans as overconfident and rash. Passepartout (the stand-in for Verne’s French reading audience) tried to propose sending passengers ahead on foot across the bridge first, followed by the train, but nobody listened to him. Instead, they backed up the train, accelerated to 100 miles an hour, and screamed across the bridge, which collapsed just behind them.

All the stations mentioned by Verne existed. Fort Bridger closed in 1890 and Fort Halleck had been abandoned in 1866. Medicine Bow, of Carbon County, Wyoming, grew around the railroad. Small at the time, it still contains less than 300 people today. Just to the north runs the Medicine Bow River, and several dozen miles to the south you’ll find the Medicine Bow Mountains. The lodgepole pine trees on these mountains made fine railroad ties.

Why the name ‘Medicine Bow?’ Native Americans considered the site ideal for disease-prevention ceremonies, and valued the trees there because the wood produced excellent bows and arrows. Upon learning this, European settlers combined the two thoughts into one name.

Medicine Bow achieved some fame when paleontologist William Harlow Reed discovered the bones of Dippy the Dinosaur there in 1898. A year later, Butch Cassidy and his ‘Wild Bunch’ pulled off a famous train robbery nearby.

Was Verne’s dramatic bridge collapse possible? He cited a train speed of 100 miles an hour. At that time, trains in the U.S. traveled around 25 mph due to the poor condition of tracks laid in haste. No steam locomotive attained 100 mph until the Flying Scotsman did it in 1934. Also, Verne wrote that the bridge collapsed just after the train crossed. Engineers know that collapse occurs when imposed stresses exceed a structure’s ability to withstand them. However, 100 mph is 147 feet per second, so a train traveling at that speed would cross a 147-foot bridge in just one second. It does take a little time for a bridge to collapse, so if the train traveled at that speed over a bridge of that length, it might just clear the far side before the bridge lost its ability to support the train’s weight. The scene is not inconceivable.

In 1872, it took two days for Fogg’s party to travel by train from Ogden to Medicine Bow. Today, you could drive that distance in a little over five hours along Interstate 80. Or you could fly to nearby Casper in just over an hour.

Soon, you Jules Verne fans will be able to purchase an anthology by the North American Jules Verne Society. When published, Extraordinary Visions: Stories Inspired by Jules Verne will contain stories by modern authors, each based on novels by the famous French author. All I have is the cover image now, but keep checking my blog for news.

With the bridge-jumping incident behind him, Fogg shouldn’t encounter any more problems as he tries to regain lost time. Nothing but clear, problem-free track from here through Omaha and on to Chicago. The two of us better keep an eye on things, you and—

Poseidon’s Scribe