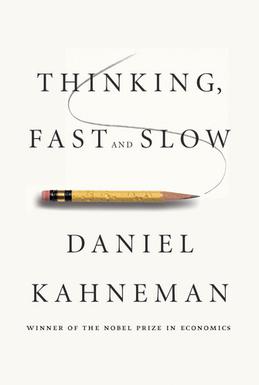

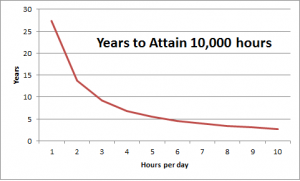

After Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers, the Story of Success showed 10,000 hours of practice equaled genius, I felt good. After all, I’d been writing almost that long, so genius and success should lie just over the next rise. A few more hours to go.

Then along came Dr. Scott Barry Kaufman, author of this article in Scientific American, saying the 10,000-hour rule doesn’t apply to creative fields like fiction writing.

Now you tell me, Doc.

His rationale makes sense, dang it. To become a genius at an activity requiring repetitive motions—oboe playing, bricklaying, pizza-making, etc.—the 10,000 hours seems logical. Some of that is creative play, but much is building muscle memory and learning more advanced techniques.

But purely creative endeavors—music composition, art, and writing—aren’t like that. Muscle memory won’t help. Spend 10,000 hours typing and retyping Sense and Sensibility, and you’ll end up a fast typist. But your skills as a novelist won’t have changed.

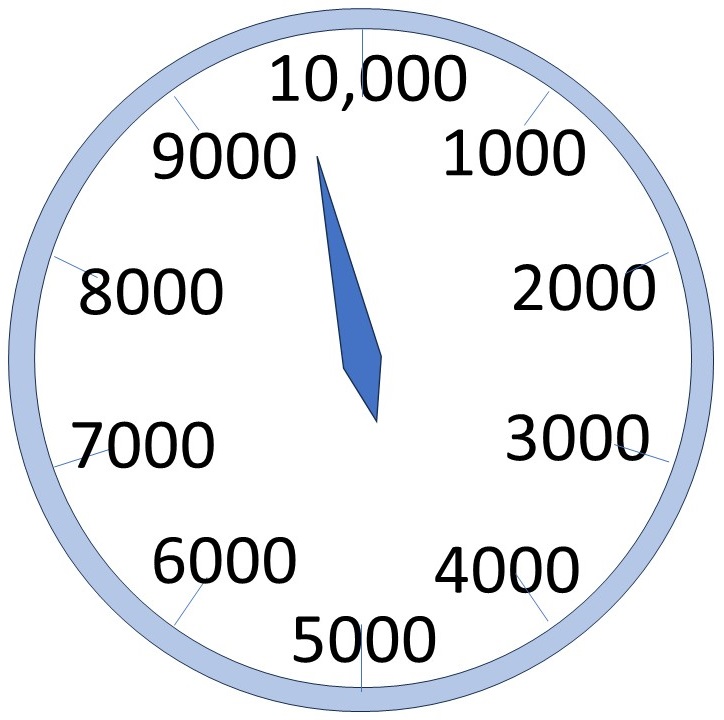

The article counts 10,000 hours of practice (also called the 10-Year Rule) as one factor in creativity, but gives that number a wide error band.

The author cites several other factors of importance to creativity. Unfortunately, a writer lacks control over some of these factors, such as talent, personality, genes, and socio-economic environment.

Lucky for us, the article provides some aspects of creativity lying within our control. For example, Dr. Kaufman states that creative people often use messy processes. If you’re the neat and organized type, you’ll have to work on correcting that.

The author says creative people take interest in a broad array of things. If you write fiction, consider writing stories outside your normal genre.

Too much specialized expertise, says Dr. Kaufman, detracts from creativity. Often, he says, people outside a field contribute the fresh insights and creative solutions. As writers, we can take care not to become overly specialized, and each of us can claim outsider status in something.

I give the doctor credit for identifying personal attributes that influence creativity, but I don’t believe you’re stuck with whatever creativity you were born with. (Nor did he imply that in his article.)

You can increase your creativity. I believe you, and all of us, were born overflowing with creativity. However, society’s pressures to conform squeezed much of that creativity out.

You can get it back through regular exercise. Here’s the exercise to try. Think of a problem. If it’s a fiction-writing problem, maybe you’re stuck for an idea, or fell into a plot hole, or need a character motivation, or seek a setting description. The problem could be anything.

Now start writing solutions as they occur to you. Include stupid ideas, impractical ideas, zany and magic ideas. It doesn’t matter—no one will see your list. Often very good ideas only emerge after thinking of dozens of bad ones first.

Yes, you may call it brainstorming. Unlike normal brainstorming, though, you’re doing this alone. Also, unlike normal brainstorming, you’re seeking more than just a good answer to your problem. You’re trying to stretch your creativity muscles. You’re retraining your mind to free it from a cage built long ago to hold it.

Maybe you’ll run dry after ten listed solutions, but I encourage you to push on. It might help to consider this–back when you were five years old, you could rattle off fifty ideas without slowing down. That’s the childlike creativity you’re looking to recapture.

If you aim to be a writer, forget about the 10,000 hours, the 10-Year Rule. That’s for others. You need creativity, and no clock or calendar can give you that. Let your inner kid loose again, this time to skip around in the infinite playground of your mind where milliseconds equal millennia and a pace is as good as a parsec.

And, there he goes, the five-year-old version of—

Poseidon’s Scribe