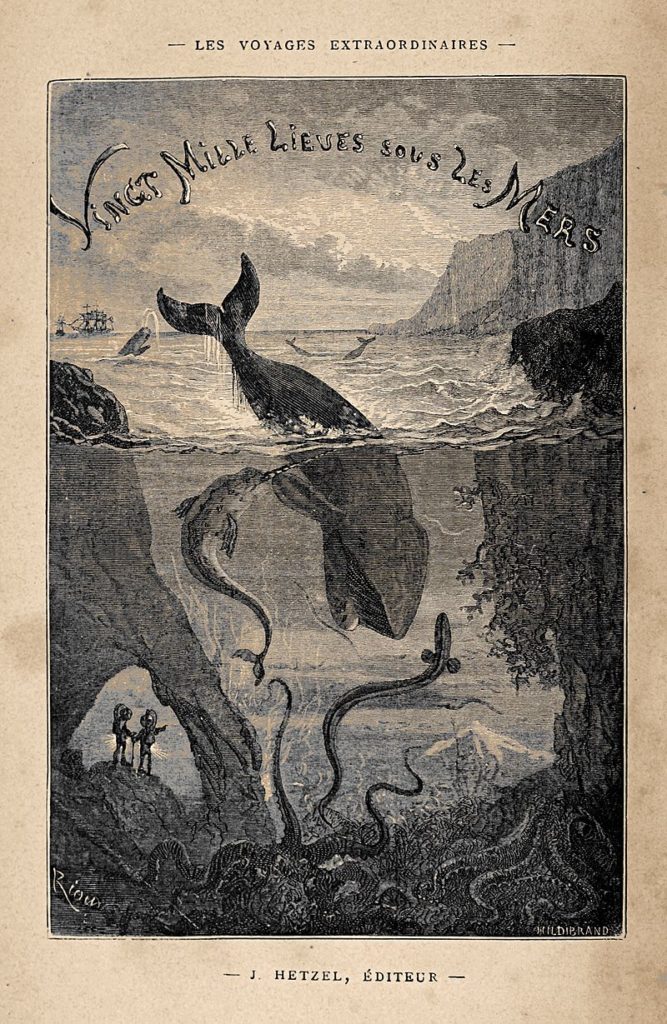

Having analyzed Conseil and Ned Land in recent blogposts, I’ll turn my attention today to the narrator of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Pierre Aronnax.

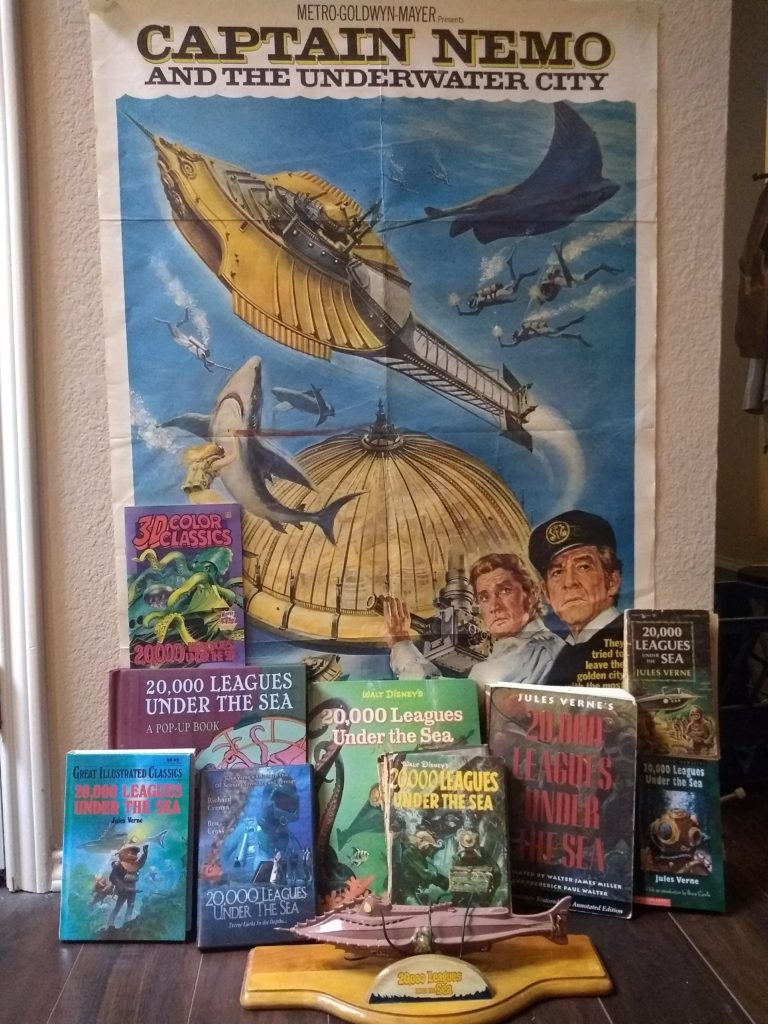

First, don’t forget to submit your best short story to the upcoming anthology 20,000 Leagues Remembered, my tribute to Verne’s undersea masterpiece on its sesquicentennial. I’m co-editing this book, along with editor and award-winning author Kelly A. Harmon of Pole to Pole Publishing. We’ll officially close for submissions on April 30, but I encourage you to submit well before then. We accept stories as we go, and every previous anthology from this publisher has filled up before its closing date. See this site for guidelines and to submit your story.

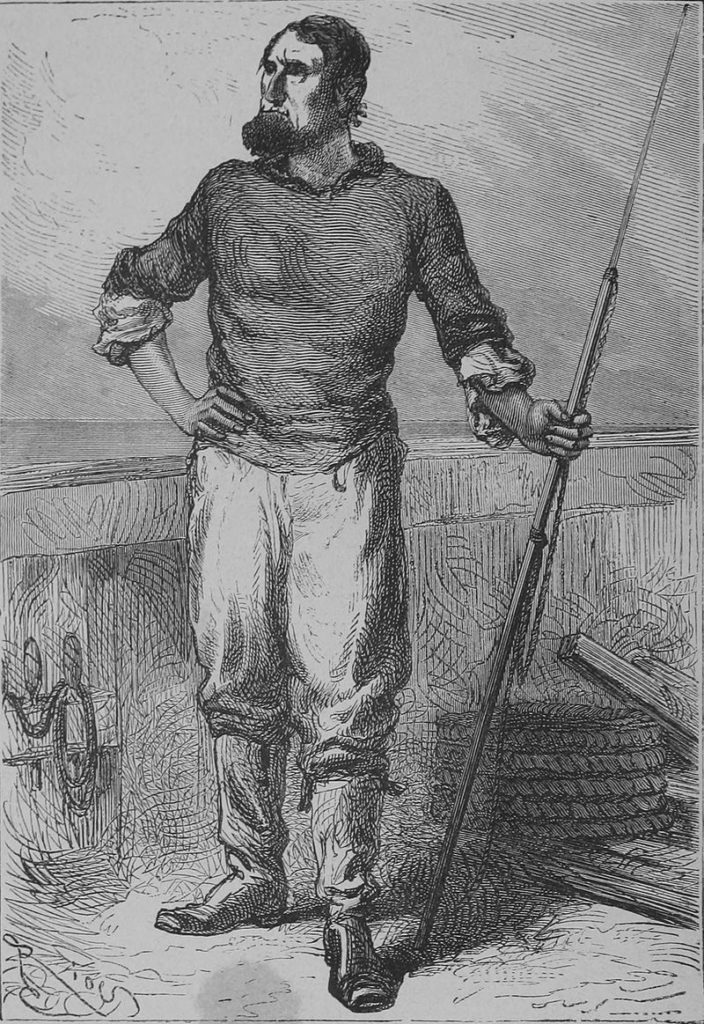

Pierre Aronnax, forty years of age, was an Assistant Professor at the Paris Museum of Natural History. He’d written a definitive book on sea creatures, titled The Mysteries of the Great Ocean Depths. Aronnax had been visiting the Nebraska Badlands and was in New York when he received an invitation to join the crew of the frigate USS Abraham Lincoln on its mission to hunt down the reported ‘sea monster.’

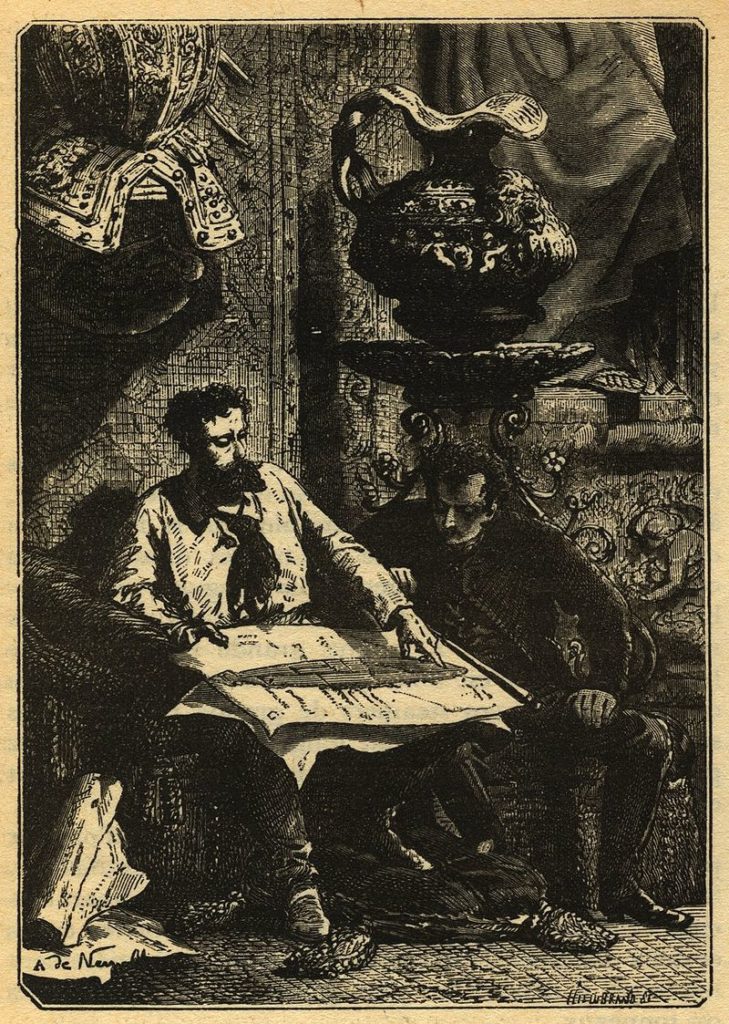

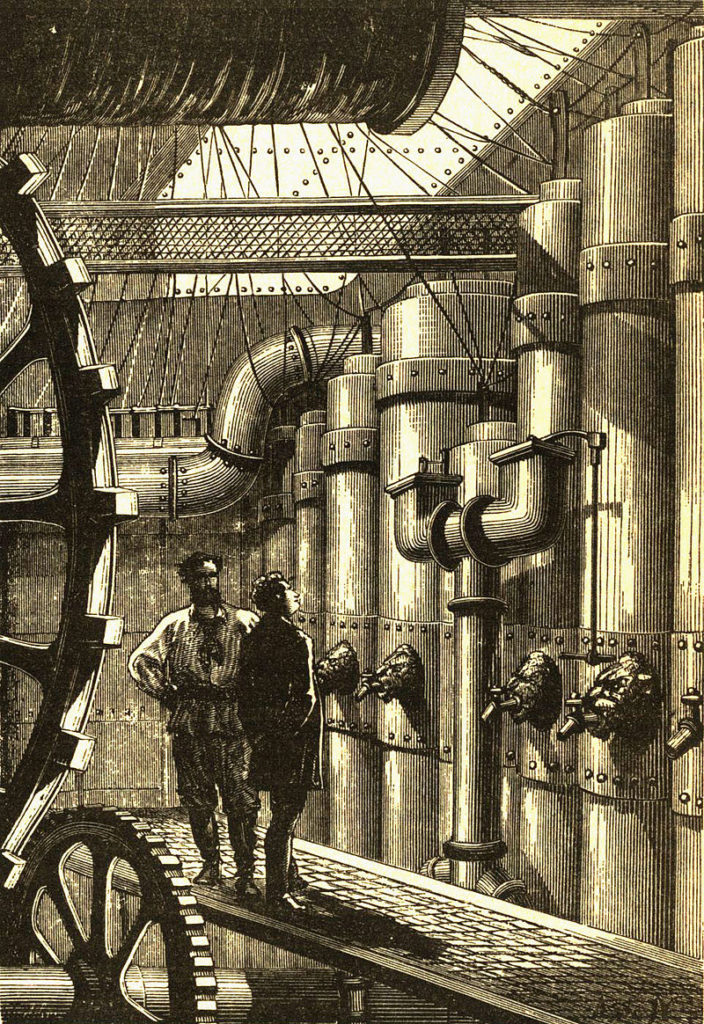

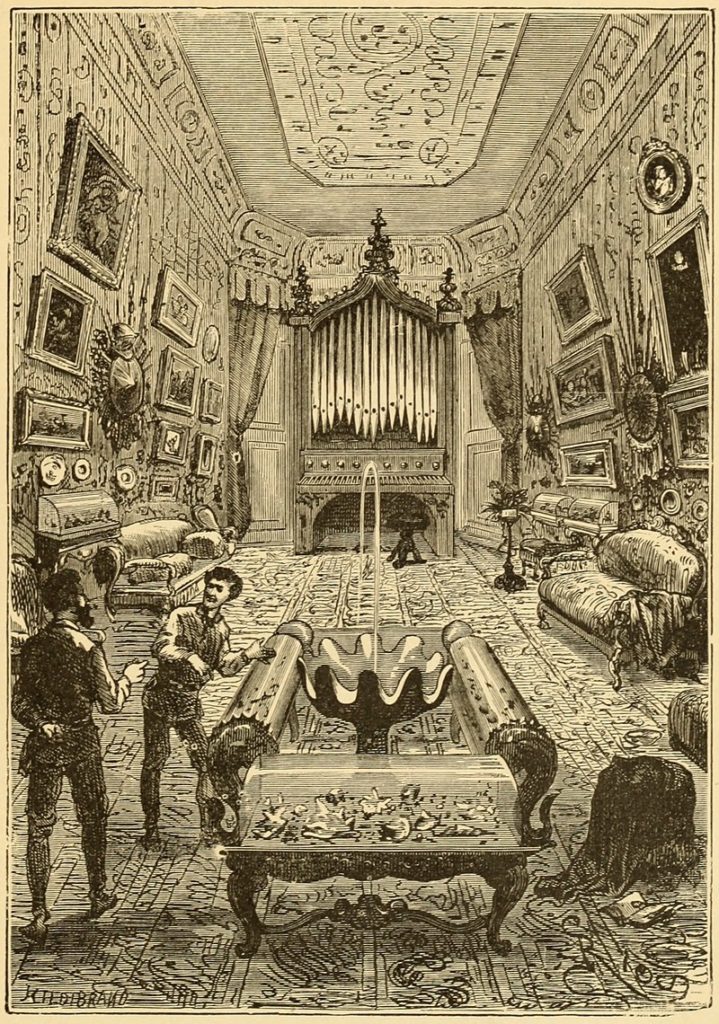

Of the three men taken aboard the Nautilus, only Aronnax is given a tour and introduced to most of the wonders aboard. Captain Nemo treats him as an approximate equal, a gentleman, while he treats the rest of his crew, and both Conseil and Ned Land, as lower-class commoners. To our modern sensibilities, this sounds absurd, but to Verne’s class-conscious readers it must have seemed understandable, even natural.

Some have theorized Verne was playing with the word ‘arrogant’ in giving the Professor his surname, but I disagree. I don’t believe Verne thought of Aronnax as arrogant or intended him to appear that way to readers. The Professor was a Nineteenth Century gentleman-scholar and behaved that way. Though he may seem arrogant to us, it is unlikely Verne would have foreseen our modern sensibilities and named his character accordingly.

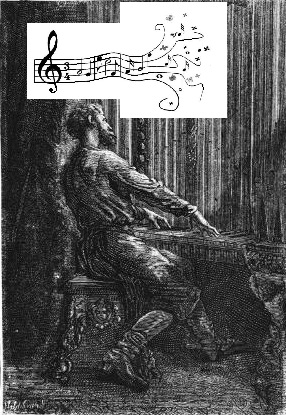

I’ve mentioned before that Conseil served as the imaginative voice of Verne. I think Aronnax and Nemo together represent what Verne aspired to be. Verne would have loved to be a scientific scholar like Aronnax and an engineer like Nemo.

That said, Aronnax is a disappointing character. He enjoys being free to examine undersea life from within a submarine, while ignoring that he’s trapped aboard. He admires the scientific and engineering genius of Nemo while choosing to ignore warning signs of the Captain’s insanity. Aronnax knows he must someday try to leave the submarine, but would prefer that date be well in the future. In short, he’s there to observe and to marvel for us, not to act in any daring way.

Modern writers can understand Verne’s dilemma. To pull off his undersea novel with all its various travels and adventures, Verne needed at least one character who was content to remain in an iron prison for the duration. Aronnax is that character, but he comes off as too trusting and too slow to act. He is carried along by events rather than causing things to happen. These aren’t traits we like to see in a main character.

In a way, we can think of Verne’s Aronnax as an unreliable narrator. The Professor gives us accurate information on the Nautilus, Nemo’s scientific and engineering prowess, and the many fish they see and places they visit. But he ignores and then rejects Ned Land’s opinion about Nemo and the Canadian’s plans for escape. Only in the end do we (and Aronnax) see that Ned was right all along.

I suppose you can guess the next 20,000 Leagues character to be analyzed by—

Poseidon’s Scribe