Excitement builds as we continue our blogtour Around the World in Eighty Days, a commemoration of the publication of Jules Verne’s classic 150 years ago. We left Medicine Bow, Wyoming just yesterday and already we’re at Fort Kearney, Nebraska.

We’ve accompanied Fogg for 19,417 miles and covered 79.1% of the total distance, but we’ve taken 83.8% of the time, so he may well lose his wager.

After just making it over the bridge at Medicine Bow on the 7th, the train passed Fort Saunders, then Cheyenne Pass, Evans Pass, Camp Walbach, and Lodge Pole Creek. After entering Nebraska, they passed near Sedgwick, then Julesburg, Colorado (then a territory). Jules Verne must have loved writing that town’s name—Julesburg. They passed Fort McPherson and then North Platte, Nebraska.

At that point, Colonel Stamp Proctor (the ruffian first encountered in San Francisco) came upon Fogg playing whist. They recognized each other, exchanged heated words, and challenged each other to a duel. Proctor proposed they conduct the duel at the upcoming Plum Creek station, but the conductor said the train wouldn’t stop there, so they must conduct the duel while enroute, in an empty car.

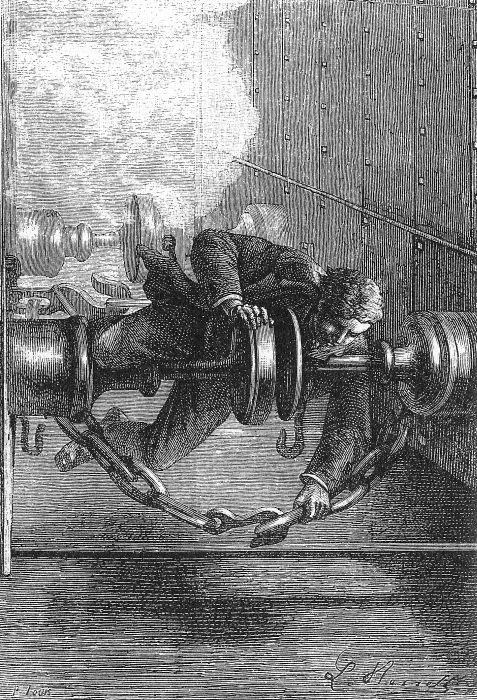

Just as the duel was about to commence, a band from the Sioux tribe attacked the train. Fogg and Proctor joined together, shooting at the attackers. The Sioux had them outnumbered and outgunned. If the train could stop at Fort Kearney, a garrison of troops could protect them. At that moment, the conductor fell from a gunshot wound. Passepartout worked his way to the linkage between the locomotive and the cars, and disconnected them. The locomotive steamed on, but the cars slowed to a stop near Fort Kearney. The soldiers rushed out and the Sioux fled. A muster showed three passengers missing—one being Passepartout.

Thirty men from Fort Kearney volunteered to accompany Fogg to rescue Passepartout. Unlike in Hong Kong, when Fogg abandoned a missing Passepartout, here Fogg delayed his journey to find his servant, a sign he’s changing, gaining sympathy for others. After they left, the locomotive backed into the station from the east. The engineer and stoker hooked up the cars and left, after Aouda and Fix refused to board. They waited at the station, hoping for a sign of Fogg’s rescue party.

Verne must have seen a map of the Union Pacific Railroad line, such as the one on this website, since all his place names appear on the map. When naming their town, the founders of Julesburg thought, not of Verne, of course, but of Jules Beni, a Colorado stagecoach robber.

During their argument, Colonel Stamp Proctor called Fogg a “son of John Bull.” John Bull appeared in newspapers as a recurring cartoon character, a symbol of the English commoner, sort of a British Joe Sixpack.

The duel seems to me an unnecessary and contrived plot device, lacking in credibility. Few actual duels occurred in the mid- to late-1800s, and the notion of dueling over which card to play in a game of whist seems to diminish Fogg’s character.

However, an attack on a train by Native Americans was plausible. Indeed, according to this website, at least two such attacks occurred at Plum Creek in 1867, one by capturing the train and the other by pulling up rails.

Railworkers call the linkage between train cars a ‘coupler.’ The original illustration from the novel shows Passepartout draped over what looks like a screw-tensioned three-link coupler.

Though Fogg required a day to get from Medicine Bow to Fort Kearney, you could fly from Casper to Lincoln in four hours, including a one-hour stop in Denver. Or you could just drive six hours along Interstate 80.

My blogtour has you interested in Verne’s book, I see. If you haven’t read it, I recommend you do. However, there exist several screen versions as well. One of the best is the 1956 movie produced by Michael Todd and starring David Niven, Cantinflas, Robert Newton and Shirley MacLaine.

For now, we must leave Fogg and Aouda at Fort Kearney, with the fates of Fogg and Passepartout unknown. What happens next? To find out, keep reading blogposts by—

Poseidon’s Scribe