When you seek comments about your writing from others, sometimes the feedback will confuse you. What do you do about that?

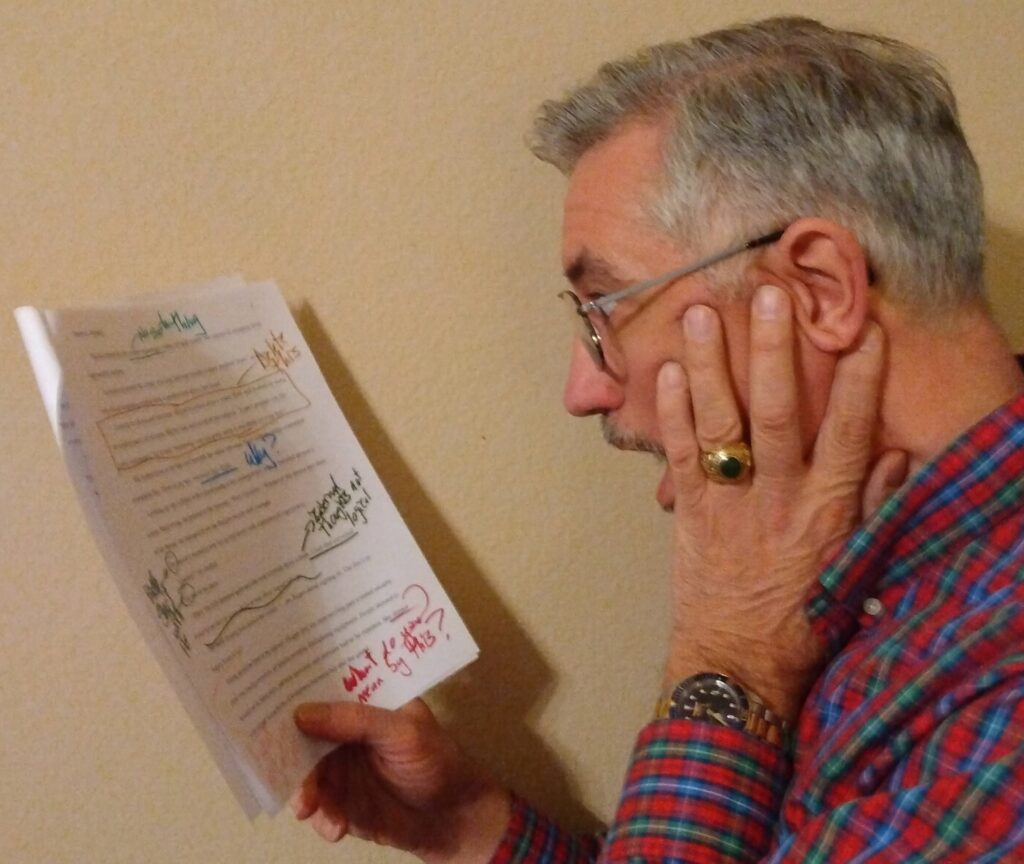

Feedback can come from critique groups, beta readers, editors, or anyone whom you’ve asked for a review. Often busy with their own lives, these commenters might, in their haste, provide comments you don’t understand.

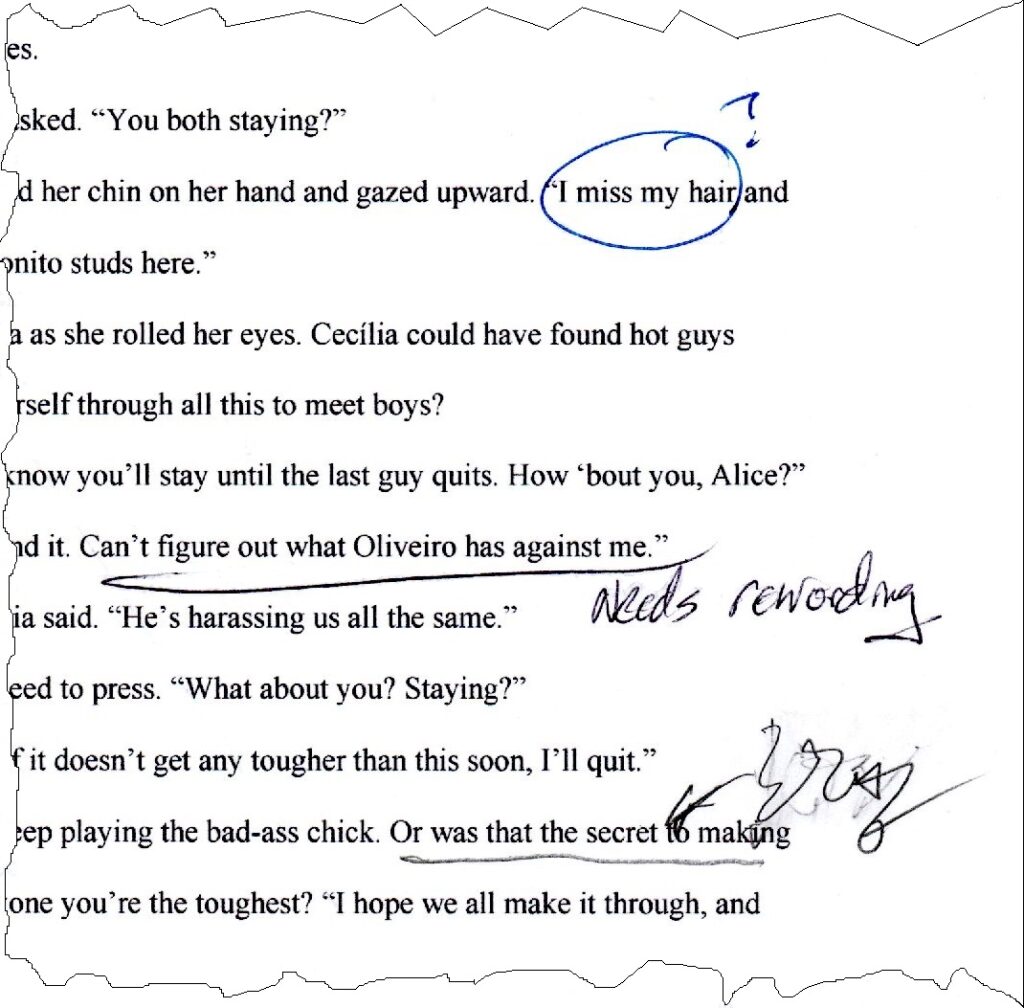

They may just leave a question mark without explanation, or give you vague advice, such as ‘reword this’ or ‘this bothered me for some reason.’ Worse, their hand-written remarks might be illegible.

As you go through your manuscript incorporating their suggestions, how do you proceed when you encounter confusing feedback? Should you ignore it, dismissing it as irrelevant? After all, if they can’t take the time to give you useful comments, why should you waste time deciphering their code?

I recommend you take such comments seriously.

The most certain way to get the strange comment decrypted is to ask the commenter to explain it. Ask the person, “You wrote [whatever it was]. What did you mean?” Such direct communication should clear up the matter, or the critiquer might not recall the comment. Either way, you’re no worse off and possibly ahead of the game.

If you can’t get back in touch with the reviewer, or if doing so doesn’t clarify things, I still urge you not to dismiss the comment. For cryptic observations, it sometimes helps to revisit them a day or two later. A fresh look and some deeper thought might reveal the comment’s meaning in a useful way.

In his book Novelist as a Vocation, author Haruki Murakami gave interesting advice on what to do about comments with which you disagree. I think his guidance also applies to comments you don’t understand.

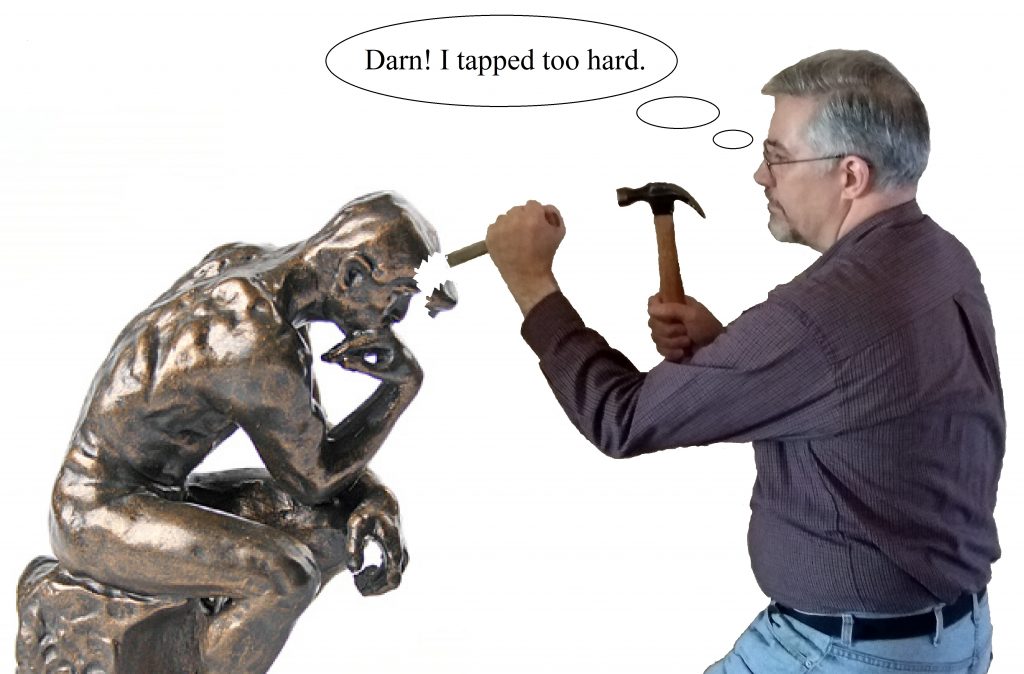

Murakami recommends making a change of some sort to your manuscript. If you disagree with the comment, you need not comply with the commenter’s suggestion, but make a change to some third way (different from both your original text and the reviewer’s proposed revision) with an eye toward improving readability.

His rationale recognizes that the reviewer did take the time to read your manuscript. As they did so, something tripped them up. Something yanked them out of your story. Since that happened to one critiquer, it could happen to one or many readers if you get your story published unchanged.

As I mentioned, this advice also works for confusing or illegible comments. In these cases, review your text again while imagining you’re a first-time reader. Read it aloud. You may well discover what the critiquer meant. Even if not, consider making a change intended to lessen confusion and enhance understanding.

Even the most bewildering comments can result in improvement to your stories, and those of—

Poseidon’s Scribe

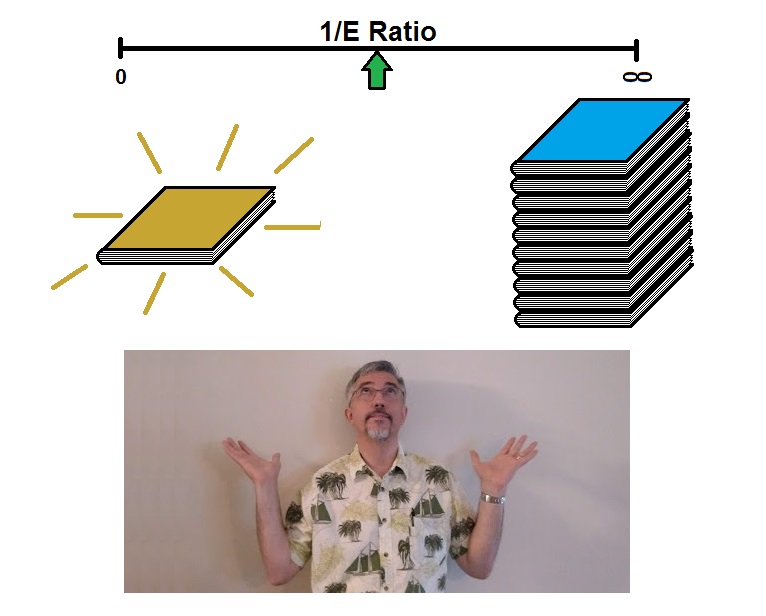

At one extreme, 1/E could be very small. In this case, you might spend twenty years polishing a novel, editing and re-editing draft after draft. Your final product might be very good and might become a classic, but you couldn’t repeat your success too many times.

At one extreme, 1/E could be very small. In this case, you might spend twenty years polishing a novel, editing and re-editing draft after draft. Your final product might be very good and might become a classic, but you couldn’t repeat your success too many times. Allow me to define what I mean by censorship. It’s the deliberate alteration of text, without the author’s permission, to make the story less offensive to the censor. This is not what a normal editor does. Editors collaborate with authors to correct errors, to make the book as good as it can be.

Allow me to define what I mean by censorship. It’s the deliberate alteration of text, without the author’s permission, to make the story less offensive to the censor. This is not what a normal editor does. Editors collaborate with authors to correct errors, to make the book as good as it can be.

That’s right. You must edit your own work before submitting it. Attack it with all the dispassionate, ruthless vigor you can. Hack, cut, and tweak until you fashion it into a story that makes you proud. Only that will make it publishable.

That’s right. You must edit your own work before submitting it. Attack it with all the dispassionate, ruthless vigor you can. Hack, cut, and tweak until you fashion it into a story that makes you proud. Only that will make it publishable.