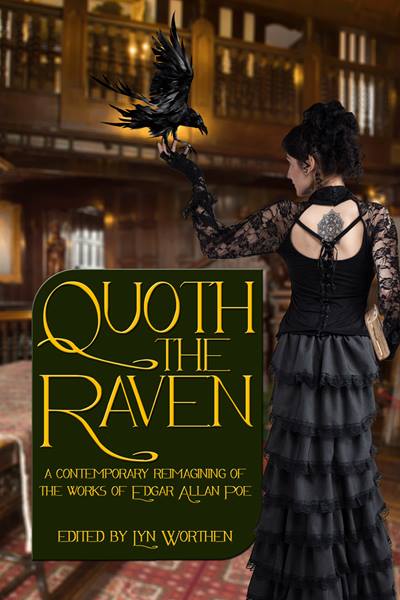

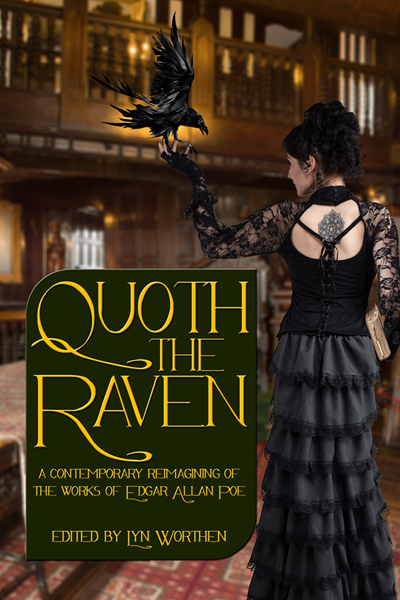

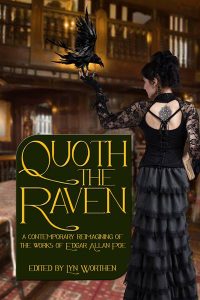

Maybe you’re not sure you want to buy a copy of the just-launched anthology Quoth the Raven. You will, once you’ve read about the authors who contributed to it. Here’s the second in a series of author interviews. Let me introduce Tiffany Michelle Brown.

Tiffany Michelle Brown is a native of Phoenix, Arizona, who ran away from the desert to live near sunny San Diego beaches. She earned degrees in English and Creative Writing from the University of Arizona, and her work has been published by Electric Spec, Fabula Argentea, Pen and Kink Publishing, Transmundane Press, and Dark Alley Press. When she isn’t writing, Tiffany can be found on a yoga mat, sipping whisky, or reading a comic book—sometimes all at once. Follow her adventures here.

Tiffany Michelle Brown is a native of Phoenix, Arizona, who ran away from the desert to live near sunny San Diego beaches. She earned degrees in English and Creative Writing from the University of Arizona, and her work has been published by Electric Spec, Fabula Argentea, Pen and Kink Publishing, Transmundane Press, and Dark Alley Press. When she isn’t writing, Tiffany can be found on a yoga mat, sipping whisky, or reading a comic book—sometimes all at once. Follow her adventures here.

Now, here’s the interview:

Poseidon’s Scribe: How did you get started writing? What prompted you?

Tiffany Michelle Brown: Honestly, I think storytelling is in my blood. I started reading when I was three, thanks to my parents’ devotion to bedtime stories. As I got older, I was one of those kids who legitimately got excited about going to the public library or the local used bookstore. And don’t even get me started about the school days when our teachers handed out Scholastic Books order forms! As soon as I learned how to write, I started walking around with a lined notebook and a pen, always prepared to jot down notes, characters, and my own stories. I have some of my earliest stories and “novels” stored in boxes in my house. They are so much fun to read, often with a glass of wine in hand.

P.S.: Who are some of your influences? What are a few of your favorite books?

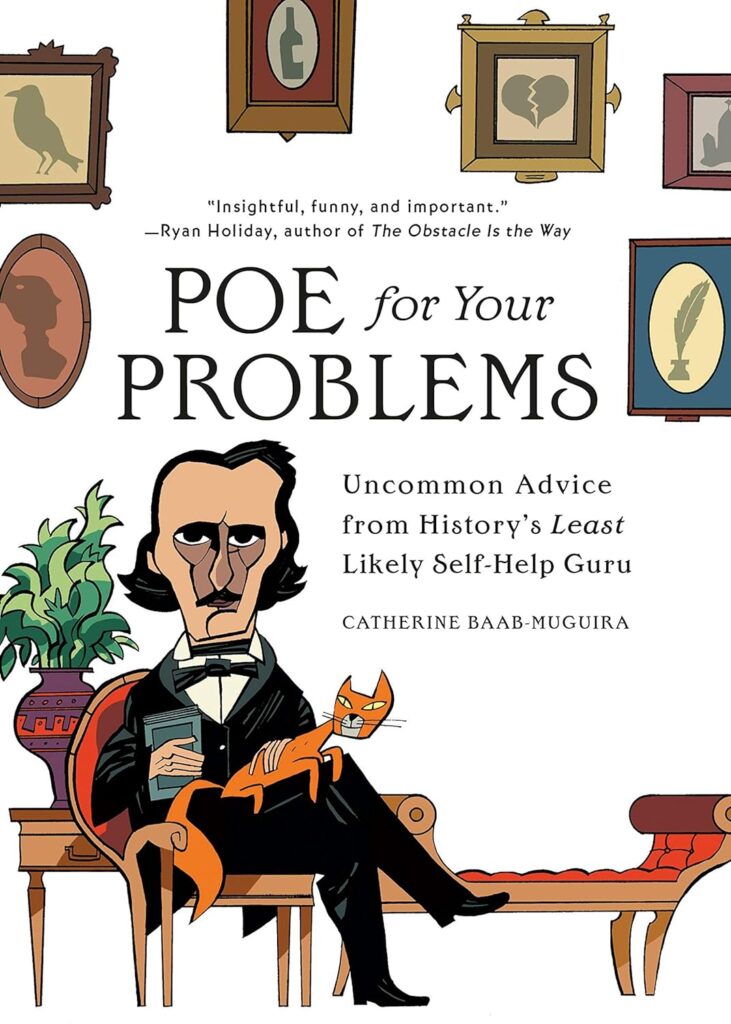

T.M.B.: Because I love the horror genre, I make it a point to read a lot of Edgar Allan Poe, H.P. Lovecraft, Shirley Jackson, and Octavia Butler. Some of my more modern influences include Neil Gaiman, Stephen King, Holly Black, and Sara Dobie Bauer. My all-time favorite books include American Gods, If We Were Villains, Wink Poppy Midnight, The Ocean at the End of the Lane, The Witch of Painted Sorrows, and Like Water for Chocolate.

P.S.: You’re an eclectic writer, having penned essays, a vampire romance novella, horror short stories, and drabbles (100 word stories). Is your muse guiding you in these various directions, are you responding to perceived demand, or is there some other reason for the wide variety of your writing output?

T.M.B.: My writing is all over the place, and I wouldn’t have it any other way! I think there are a couple reasons my work is so varied. I read voraciously and across genres – sweet romance, horror, steamy erotica, science fiction, YA, mysteries, superhero graphic novels – and like many authors, my current work tends to emulate a bit of what I’m reading. Additionally, I’m a sucker for a themed anthology. I scour calls for submissions to see if certain themes or prompts get my brain whirling. If a kernel of an idea starts developing in my head, I just go with it and see what happens. I love the spontaneity and the freedom to write about whatever strikes my fancy.

P.S.: Suppose you’ve traveled through time and met yourself at a point when you were first thinking of being a writer. What one thing do you tell this younger version of you?

T.M.B.: Believe in your work, and never let a rejection hold you back. There are people out there who will love your work just as much as you do. It’s all about finding those people, and it will happen.

P.S.: Your story “My Love in Pieces” appears in Quoth the Raven and was inspired by Poe’s story “Berenice.” Please tell us a little about your story and why you chose to write it.

P.S.: Your story “My Love in Pieces” appears in Quoth the Raven and was inspired by Poe’s story “Berenice.” Please tell us a little about your story and why you chose to write it.

T.M.B.: I loathe censorship, especially when it comes to literature. While reviewing Poe’s works and trying to decide which story or poem I wanted to retell for a modern audience, I learned that when “Berenice” was first published, it caused quite an uproar. Readers contacted the Southern Literary Messenger to express their opinion that Poe had gone too far, and he later self-censored the story. This little tidbit piqued my curiosity, so I read “Berenice.” The body horror in that story is so unsettling, and I wanted to challenge myself to write something just as disturbing. It also seemed like the perfect opportunity to resurrect a censored work, and I’m all about that. Thus, my story, “My Love, In Pieces” came to be.

P.S.: You’re a newlywed; how wonderful! How has married life impacted your writing?

T.M.B.: Thank you! In January, it’ll be one year! Funny enough, the biggest impact on my writing doesn’t have anything to do with my creativity and has everything to do with the administrative side of getting married. I made the choice to change my name, but I continue to publish under my maiden name, Tiffany Michelle Brown, and that means that I’m suddenly writing under a pseudonym, which I’ve never done before. So that’s been a bit of an adventure!

And I do want to give a quick shout out to my husband, who is consistently reminds me that I need to carve out time to work on my writing, because he knows how important it is to me. He is endlessly patient and supportive. And he’s the person who helps me celebrate every acceptance, too, often with chocolate and whisky.

P.S.: What are the easiest, and the most difficult, aspects of writing for you?

T.M.B.: The easiest part of writing is getting completely lost in characters. If you create them just right, they take over and drive the ship. I’ve had these incredible, almost out-of-body experiences where I’ll just type and type without a lot of awareness of what’s happening on the page; I’m just getting the story out. And then I go back to read what happened, and I’m totally surprised by the choices my characters have made. It’s a really strange, cool feeling.

The most difficult parts of writing are time management and constant rejection. I work in marketing and communications by day, so I spend a lot of time in front of a computer screen. It’s hard to fire up the laptop after so much work-related screen time, so I have to stay really motived. Additionally, you have to develop thick skin to succeed in this business. I used to get really bummed out by rejections (and I still do from time to time), but I’ve made it a habit to use rejection as a motivator. When I get a rejection, I immediately research new markets for a story. It just wasn’t the right fit and my job is to find the editor who loves my work.

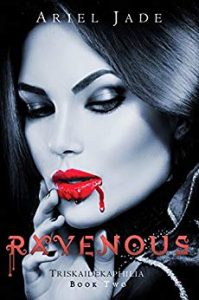

P.S.: You contributed “A Taste of Revolution” in Ravenous (Triskaidekaphilia Book 2). It’s an anthology of vampire stories. Please give us a taste of your story.

P.S.: You contributed “A Taste of Revolution” in Ravenous (Triskaidekaphilia Book 2). It’s an anthology of vampire stories. Please give us a taste of your story.

T.M.B.: Jules Hammond thinks the vampire way of life in the Republic of New Vampyrium is a crock of shit. Her brethren are ruled by a pair of nihilistic tyrants, quarantined in what was once Romania, and forbidden to prey upon humans. Even worse, Jules could be staked and beheaded for voicing her disdain in public.

In the underground safety of her lab, Jules spends her nights synthesizing artificial blood infusions, talking a lot of political smack, and longing for freedom.

When a chance encounter with a gorgeous vamp from her past—now the crowned prince of the Republic—ignites lustful desire in Jules, she’s both twitterpated and confused. As she struggles to reconcile her overwhelming and exceedingly annoying feelings for Prince Fabian, Jules is offered a dangerous opportunity to free the vampire race from the clutches of its depraved monarchy.

Who knew the fate of bloodsuckers everywhere would depend upon a blue-haired blood chemist with rage for days and budding feelings for a man who represents everything she hates.

Essentially, this in a retelling of the Cinderella story…with vampires, political tension, bad wigs, tons of action, and a foul-mouthed heroine. I loved writing every word of it!

You can read more about “A Taste of Revolution” here and buy a copy of the anthology in all its vampire romance goodness here.

P.S.: You just met an interested reader in an elevator. The reader asks, “What sort of stories do you write?” The doors will open soon, so what short answer do you give this reader?

T.M.B.: I write sinister horror stories, steamy erotica with beautiful language, and paranormal romance stories featuring sarcastic, plucky heroes and heroines.

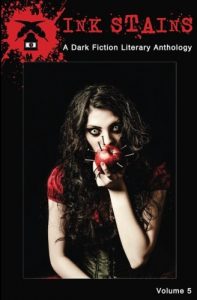

P.S.: To the anthology Ink Stains: A Dark Fiction Literary Anthology, you contributed your story “He Smelled Like Smoke.” At the time, you said that story contained your favorite closing line. Without revealing that line, can you describe the moment you thought of it and knew it was right?

P.S.: To the anthology Ink Stains: A Dark Fiction Literary Anthology, you contributed your story “He Smelled Like Smoke.” At the time, you said that story contained your favorite closing line. Without revealing that line, can you describe the moment you thought of it and knew it was right?

T.M.B.: To this day, I still love that line. “He Smelled Like Smoke” is a dark, dark, dark horror story, and the closing line is spoken by a monster. It conveys nonchalance and absolute finality, and I hope it makes the reader think, Oh shit.

You can read more about “He Smelled Like Smoke” here and purchase the Ink Stains anthology here.

P.S.: What is your current work in progress? Would you mind telling us a little about it?

T.M.B.: Funny enough, the vampire romance bug has bitten once again! I’m working on the first novella in what I hope will become a trilogy.

For Victor, a lonely, introverted vampire, working the night shift at a college library is the perfect cover – darkness, routine, and just enough connection to the outside world to remind him of what he once was. It’s an easy way to spend eternity—until cocky student Elliot starts visiting the stacks late at night to study Victor and ask him vampire-related questions. Victor tries to play it cool, feigning indifference, but he’s desperate to figure out Elliot’s intentions. Is he a threat? A vampire fanboy? And which scenario is worse? It doesn’t help that Victor’s instincts for self-preservation are growing more and more at odds with his budding attraction to Elliot. When the student makes a bold move that changes their relationship, Victor decides to kill him… but he’ll have to see past Elliot’s ginger curls and devilish smile to take his life.

Poseidon’s Scribe: What advice can you offer aspiring writers?

Tiffany Michelle Brown: No matter what you write, there is an audience for it. Write what you love and do it with heart. There’s no voice like yours on this planet, so believe in it and share it. When you do, you’ll find editors and readers who love your work. And there’s no better feeling as an author than finding your tribe.

Thank you, Tiffany.

Readers can follow Tiffany Michelle Brown at her blog, on Facebook, on Twitter and on Goodreads.

Poseidon’s Scribe