Do you love reading mysteries? Ever think of writing one?

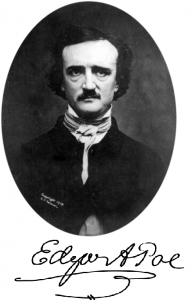

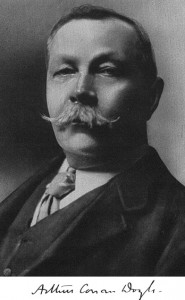

The genre was invented by Edgar Allan Poe and popularized by Arthur Conan Doyle in his Sherlock Holmes stories. It remains a popular genre with a devoted readership.

The genre was invented by Edgar Allan Poe and popularized by Arthur Conan Doyle in his Sherlock Holmes stories. It remains a popular genre with a devoted readership.

The mystery genre is hard to define. All fiction involves an element of mystery, since there’s always a conflict and the reader doesn’t know how the protagonist will resolve that conflict. Here we’ll speak of stories where the focus is on the puzzling aspects of the conflict, which is often a crime or some unexplained phenomena. In addition, the sleuth in the story uses attention to detail and deductive logic to solve the mystery.

In your mystery story, make sure the mystery itself is something important, something the reader will care about. That’s why there are so many murder mysteries, and so few involving a missing 99¢ comb.

Before writing your story, develop various timelines or storylines:

1. First is the actual timeline of events in which the real perpetrator commits the act. This must be logical and in accordance with various character’s motivations. As author, you’ll be the only one who knows this one.

2.a., 2.b, 2.c, etc. You may need a series of fake timelines, in each of which one of the other suspects could commit the act. These need not be completely logical or reflect character motivations exactly, but at first your sleuth won’t know that.

3. A timeline pieced together by your sleuth, formed through evidence and logical deduction.

4. You might even have a separate timeline that is revealed to the reader. However, Timeline 4 usually matches Timeline 3.

Most mysteries involve the commission of a crime. To do so, a criminal must have means, motive, and opportunity (MMO). The challenge for the sleuth is that either (1) several people seem to have all three, or (2) nobody seems to have all three. Of the three necessary parts of MMO, motive is often the first part presented to the reader.

Among frequent readers of the genre it’s considered unfair to (1) withhold evidence from the reader that the sleuth knows, including specialized skills or knowledge, or (2) have the sleuth confront the guilty suspect with insufficient evidence (that wouldn’t gain a conviction in court) but still the criminal breaks down and confesses.

Your writing challenge is to present the reader with all the evidence needed to solve the mystery, but to make the puzzle difficult enough that the reader would rather just read to the end to see how the sleuth cracks the case. Bear in mind the necessary evidence need not be emphasized in your story, just present. It could be buried in the middle of a paragraph. Or you could distract the reader’s attention with some dramatic action that happens to include a piece of evidence easy to gloss over.

The genre has been so well explored, it’s difficult to think of mysteries that haven’t been done. For example, I wish you luck in thinking up a new version of the locked-room mystery, where a crime is committed in a sealed enclosure where the only entries are locked from the inside.

For that reason, writers of mysteries these days seem to be focusing on the character of the sleuth, or the setting. In today’s market, the way to set your mystery apart is to have a very compelling sleuth. The minimum attributes for this character are: (1) attention to detail, and (2) an ability to deduce a chain of events from disparate facts. Or you could have two sleuths working together, each of which has one of these traits.

Another way to distinguish your mysteries from others is to use a historical or unusual setting. Depending on how far back a time you choose, it could present a real challenge for your sleuth due to the lack of modern crime investigation technologies.

Did this blog entry inspire you to write a mystery story? Leave me a comment and let me know about it. Just make sure the answer to whodunit isn’t–

Poseidon’s Scribe