Does the current draft of your story seem uninteresting? Do you have to wake up your Beta readers after they get through the first page? Perhaps the stakes aren’t high enough.

Earlier this week, I attended an excellent Zoom talk by author Amber Royer called ‘Giving Everyone a Stake in the Story.’ That talk inspired this blogpost, but, as usual, I’m putting her presentation into my own words.

What, exactly, is a ‘stake?’ As a noun it has two meanings, the first being a stick or post driven into the ground, but we’re interested in the second meaning. One theory suggests that people in medieval Europe would wager on events (jousts or other contests) by placing bets on wooden posts—stakes. Over time, they referred to the bets themselves as ‘stakes.’

A stake, then, is the thing being risked, the thing that could be won or lost depending on an outcome of a future event.

What do the key characters in your story have at stake? If they aren’t taking some risk with a chance to win or lose something, your readers won’t care about them.

To have a stake, the characters must want something. The more important that thing is and the more they want it, the more interesting your characters will be. Stakes are tied up with motivations.

The thing your character wants could be tangible, like a physical object, or a job promotion; or it could be intangible, like love, status, or respect. Maybe it’s not something they want, but something they want to avoid, like humiliation, defeat, loss of self-respect, injury, death, etc.

Once you decide what your characters have at stake, think about how far they’re willing to go to get what they want, or avoid what they don’t want. Would your characters give up money, time, their reputation, their honor, a friendship, their life?

Stakes aren’t just for protagonists. Your antagonist needs a stake, too. Consider thinking about this even before developing your protagonist. What does your ‘bad guy’ want, and how far is she willing to go to get it?

Your story might also include a ‘Stakes Character.” This character personifies and represents what’s at stake for your protagonist. Often both the protagonist and antagonist strive for the Stakes Character, or want what that character has, but they use different means.

For example, in the movie Mary Poppins, George Banks is the protagonist. Mary Poppins is the antagonist, and the children, Jane and Michael, are the Stakes Characters. George thinks his career as a banker is what’s at stake, but really, it’s his role as a father. Mary opposes his focus on his career and works to make him realize being a good father is far more important. Seen in that way, they’re both fighting for the children.

Even your minor characters will have stakes. However, don’t let them steal the show away from the main protagonist/antagonist conflict.

How do you find out what’s at stake for your characters? Ask them. (Well, not out loud if you’re in public—that would seem weird.) Ask tough, deep questions. Think about their answers and let those deep, personal confessions influence how you write about those characters in the story.

Amber Royer credits editor Donald Maas with categorizing stakes as Personal, Public, or Ultimate. Personal stakes are inside, usually unknown to the world. Public stakes are known and often shared. If the protagonist fails, more than that one character would be affected. Ultimate stakes are the really deep ones underlying all other motivations. They’re at the end of the ‘why?’ chain of questions. They’re the ones you’d give your life for. A single character can have one, two, or all three types.

If your story is tedious or dull, or the characters seem flat and lifeless, raise the stakes! Give them something more to win or lose. Make them willing to risk more. If that doesn’t work, ask yourself how you’d write your story if you were more like—

Poseidon’s Scribe

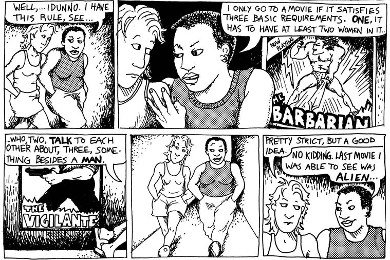

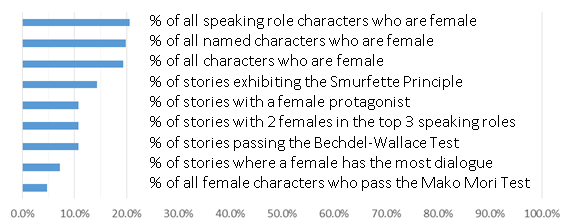

This blog post comes with a giant disclaimer. I’ll be discussing general tendencies, not rules. Rather than concentrating on having a female character “talk like a woman,” focus instead on having her talk consistently with her personality, age, nationality, time period, upbringing, geographical location, and gender. In other words, the way your characters talk depends on a lot more than gender.

This blog post comes with a giant disclaimer. I’ll be discussing general tendencies, not rules. Rather than concentrating on having a female character “talk like a woman,” focus instead on having her talk consistently with her personality, age, nationality, time period, upbringing, geographical location, and gender. In other words, the way your characters talk depends on a lot more than gender. Today I’ll consider the topic of characters getting too big for their britches, and assuming a bigger (or different) role than the one planned for them. When this happens in your writing, should you take it as a good thing or a bad thing?

Today I’ll consider the topic of characters getting too big for their britches, and assuming a bigger (or different) role than the one planned for them. When this happens in your writing, should you take it as a good thing or a bad thing?

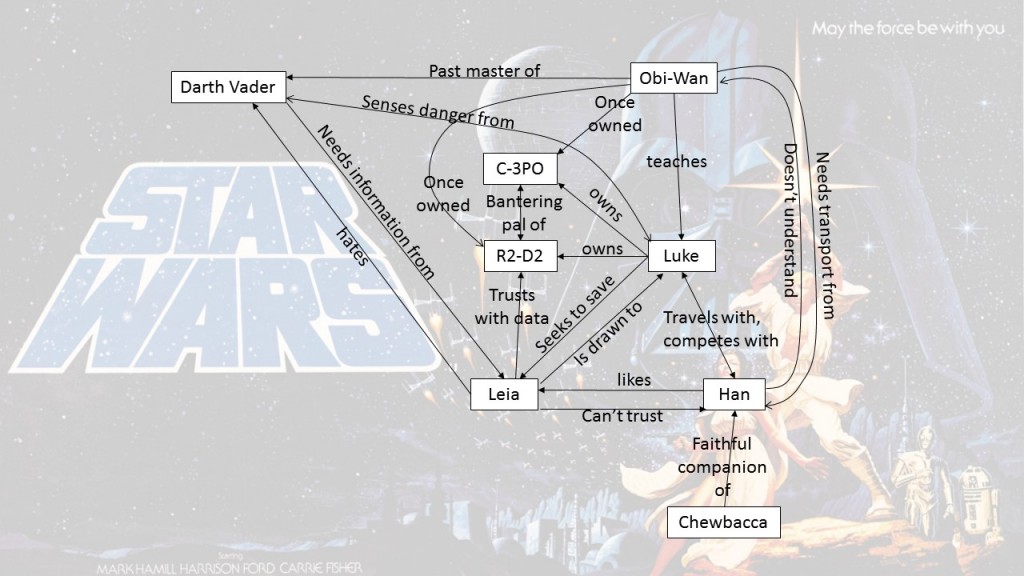

The one I’m showing here, for the first Star Wars movie, A New Hope (Episode IV), is for illustrative purposes only and is not complete or necessarily accurate. My only intent is to show one possible example for a case familiar to most readers. To see many other sample Character Relationship Maps, do an Internet search for that term and click on images.

The one I’m showing here, for the first Star Wars movie, A New Hope (Episode IV), is for illustrative purposes only and is not complete or necessarily accurate. My only intent is to show one possible example for a case familiar to most readers. To see many other sample Character Relationship Maps, do an Internet search for that term and click on images.