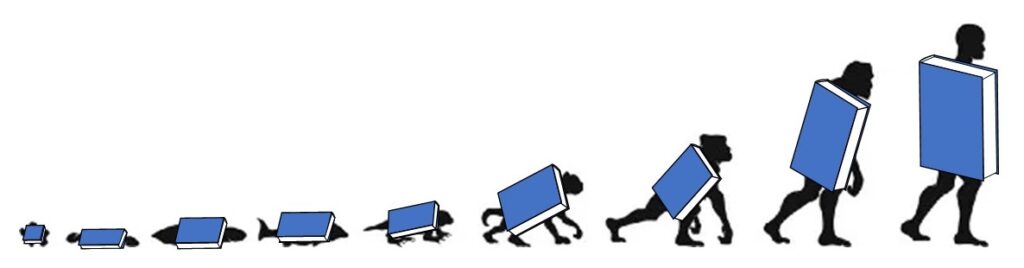

As you write it, your book will evolve. Think of this process as a scientist thinks of an organic species.

The scientific theory of evolution holds that genetic variations within individual members of a species produce an organism slightly different from its parent or parents. The differences allow it to fit into its environment better, or worse, or with no change, in comparison with its ancestors. Those organisms less able to fit do not survive. Those that fit better, do.

Further complicating the process, the environment changes too. Usually this occurs at a much slower rate than the generational, genetic changes within a species, but sometimes the environment alters in sudden and catastrophic ways.

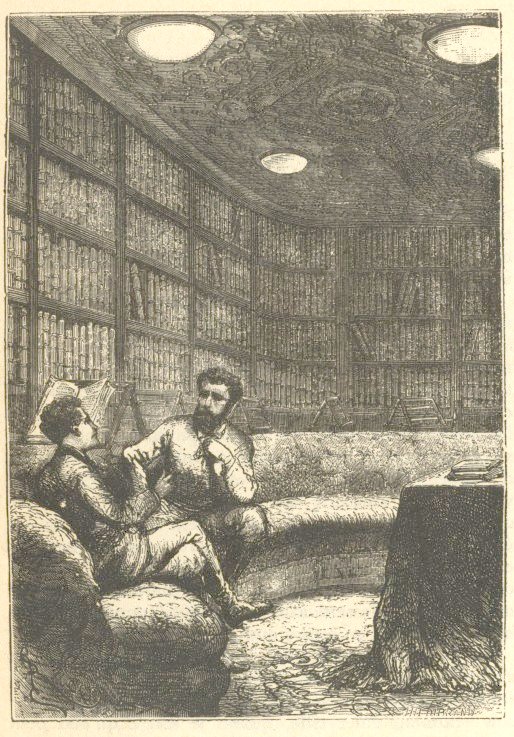

How is this like the book you’re writing? Your book begins as an idea, amoeba-like, single-celled, floating in the nourishing sea of your mind. That sea not only feeds the new-born amoeba-book, it adds cells, adds complexity in a benevolent, parental way.

Soon that environment changes. Your fledgling book idea doesn’t swim alone in your mind-sea. Other book ideas compete for food there. Any given book idea jostles against others while you probe and examine each one, scrutinizing them all for weaknesses.

Your book then grows more complex and becomes a fish with internal structures. Physically, a few pages of notes. It’s survived the rough-and-tumble of competition with other book ideas to adopt this new form.

As you create early drafts, your book becomes an amphibian. A manuscript, though rough in form. Time for it to emerge into a new and harsher environment. You push your book up to the light, to crawl onto the beach of criticism where it will encounter a critique group or a beta reader.

A cruel life awaits your book as it creeps about in this unfamiliar world. Editor-predators lurk there, ready to detect weak spots and pounce. If genetic variations (revisions) prove favorable, your book adapts, becomes more reptilian, fits in with the environment by surviving encounters with predators.

Your book continues to evolve during a long period of revision. It becomes strong, lean, and complex, with few remaining weaknesses. A mighty and fearsome creature, it rules its world.

A meteor strikes.

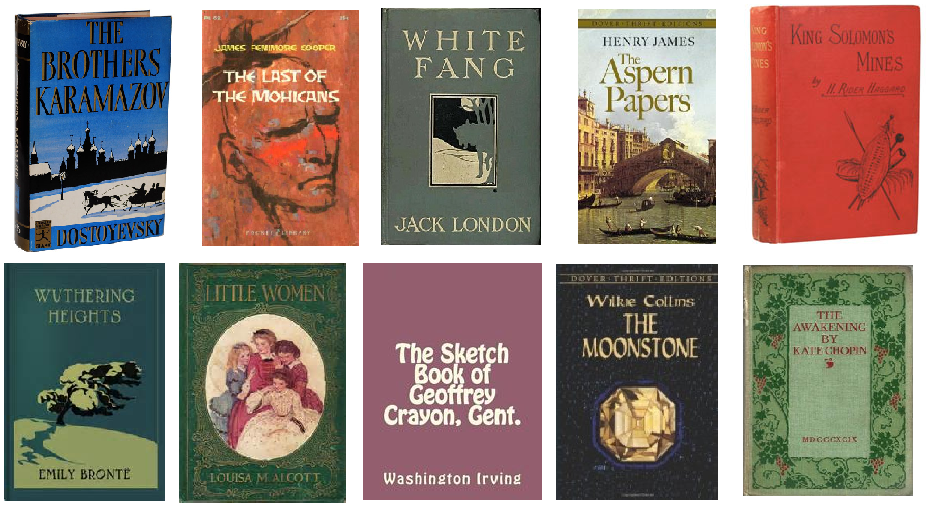

You got the book published. The environment explodes into a chaotic new form. No longer a gigantic dinosaur, striding unchallenged, your book is a tiny mammal, a mouse scurrying about, competing for readers against innumerable other creatures.

These readers provide the sustenance your book needs—sales. But some readers become critics. A few of those critics treat your book well. Many other critics claw, slash, and gnaw at it.

Many books cannot adapt to this treatment and die out. Others manage to survive, despite the adverse criticism. Published in text form, your book may evolve in new ways. It can take the form of an audiobook. It can be adapted into a play, a movie, a TV show, a graphic novel, a comic book, a video game, etc.

Adapted and evolved to survive in various environments, your book stands erect, spreads throughout the world, and endures.

I wish you luck as you help your book along its evolutionary path. May it survive many epochs. I’m hoping the same success awaits books by—

Poseidon’s Scribe