Today I’m happy to welcome another fellow author who contributed a story to the Hides the Dark Tower anthology. It’s Andrew Gudgel, science fiction author, Chinese poetry translator, and a past winner of the Writers of the Future contest.

Here’s the interview:

Here’s the interview:

Poseidon’s Scribe: How did you get started writing? What prompted you?

Andrew Gudgel: I got interested in writing in high school–essays, poetry, stories. You name it, I tried writing it. I wrote a lot, all the way up through college. Then I went and joined the Army. For ten-plus years I did other things. Fortunately, writing was still waiting for me when I came back.

P.S.: Who are some of your influences? What are a few of your favorite books?

A.G.: I’m not sure I could nail it down to just a couple of authors because I feel a writer should be influenced by all the things he or she reads. But just to pick an example at random: Jorge Luis Borges’ “Ficciones.” He wrote such interesting stories, not only in terms of theme, but in style. Reviews of books that don’t exist. Descriptions of infinite libraries. Fictional worlds that become real and begin invading ours. Borges made me aware of possibilities in fiction that I’d never imagined existed.

I also think a writer–any writer–should read broadly in categories outside his or her preferred genre of writing, and for pleasure as much as for writerly education. For example, I read as much poetry and as many essays as I can, simply because I enjoy both.

P.S.: You recently completed a graduate degree at St. John’s College in their Great Books program. How has that affected your fiction writing?

A.G.: One of the best things about St. John’s is that you read the Classics in philosophy, religion, science, literature, politics, society and history. You learn that there are questions and themes that are eternal in literature and in life. (Plus it gives you plenty of neat ideas and material to snitch for use in your own stories.) It affected my fiction writing by making me more focused on character and what happens inside each and every one of us as we move through life. SF has the advantage that you can create situations and characters that don’t (or don’t yet) exist, which allows you to explore your characters and the human condition in ways other genres simply can’t.

P.S.: Your primary genre is SF, correct? How did you become interested in writing in that genre?

A.G.: I do primarily write SF, but will follow a story wherever it leads me, be that SF, fantasy or literary. I fell in love with SF early on–my father used to read Ray Bradbury stories to me and my brother on summer nights when we were little. And when I read H. Beam Piper’s “Space Viking,” it made enough of an impression that I still remember it, forty-odd years later. Plus I’ve always been fascinated by science, technology, and gadgets.

P.S.: What other authors influenced your writing?

A.G.: In terms of science fiction, Ray Bradbury, William Gibson, Charlie Stross, and Robert Heinlein. As for prose style, Seneca and Sir Francis Bacon. Both were writers of the short, pithy sentences I aspire to.

P.S.: In what way is your fiction different from that of other SF authors?

A.G.: I’m very interested in the human/character side of SF: how we interact with technology, how we’ll be different/the same in the future. I hear about these cool–but true–uses of technology that are completely unexpected, and that gets me excited and fired up to write. For example, in India, a tech company is using hand-woven silk strips for their diabetic test kits because it’s cheaper than imported plastic. That’s a low-tech/high-tech solution. Low tech in that it’s local weavers and hand-made fabric. High tech in that it’s a creative human solution to a pressing problem. When I write, I try to concentrate as much people on and how they solve their problems as on the technology itself.

P.S.: In Hides the Dark Tower![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000039_00001]](https://stevenrsouthard.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/HidesTheDarkTower-DigitalCover-FINAL2-200x300.jpg) , your story is “The Long Road Home,” an exciting story involving an immense alien tower. Can you tell us about the protagonist?

, your story is “The Long Road Home,” an exciting story involving an immense alien tower. Can you tell us about the protagonist?

A.G.: Wang Haimei is a “Tower Diver,” a person who uses parachutes and hydrogen balloons to explore the inside of a hollow building that’s ten-thousand stories tall. There’s nothing left of the aliens who inhabited the tower, except for the very rare artifact which makes the finder instantly (and incredibly) wealthy. Haimei has just the right combination of meticulous attention to detail, love of adventure, and desire to get rich that all true tower-divers have. But she lost her fiancé, Moustafa, in a tower-diving accident a year ago, and this trip is her first one back since then. When a jealous competitor sabotages her gear, Haimei decides to try and walk back up to the exit at the top of the tower, even though she knows she’ll die long before she gets there. She discovers a kind of quiet courage that keeps her from giving up. As she walks, she discovers she’s being followed—perhaps by an alien that’s remained behind, perhaps by the shade of one long gone. She comes to appreciate the company, though, and uses the time spent walking to come to terms with death–both Moustafa’s and hers.

P.S.: In addition to writing fiction, you translate Chinese poetry. Have you found that your translation work improves your writing of stories in English, or is there no connection between these pursuits?

A.G.: I’ve found that translating, and translating poetry, has had a big influence on my writing. Knowing another language lets you see the world in different ways and makes you aware of connections you might never have thought of. For example, in Chinese nouns have measure words. (They’re roughly equivalent to the word “cup” in “one cup of coffee.”) But every noun has a measure word in Chinese, and they’re often reused. Which groups nouns into “categories.” Snakes and rivers use the same measure word; clouds and flower blossoms share one, too; so there’s a linguistic relation between certain nouns in Chinese that doesn’t exist in English. Being able to see—and make—new connections has made my writing richer. And poetry is a compact, image-rich art form that requires you to pack a lot into a small space. Perfect for learning both imagery and economy of words.

P.S.: What is your current work in progress? Would you mind telling us a little about it?

A.G.: I’ve got a couple of irons in the fire right now—revisions, that sort of thing. The one I’m currently working on is an alien invasion novel/novella, which focuses on different peoples’ experiences of the event, and in which the aliens are only ever glimpsed at. I was inspired by the fact that you never see the whole shark until near the end of “Jaws.” So the glimpses the characters get throughout the story—are they the aliens or just alien technology? I was also very interested on the effect of such as big disaster would have on people—both as individuals and in groups—and not making the aliens central to the story allows me to focus more on that aspect.

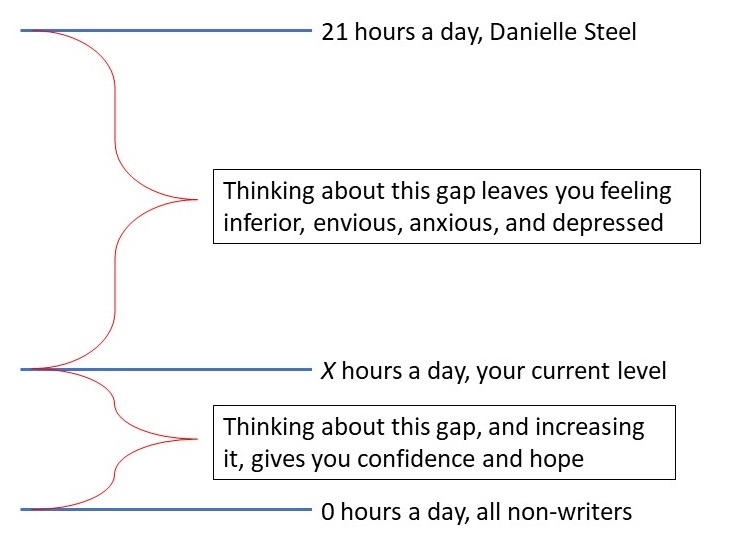

Poseidon’s Scribe: What advice can you offer aspiring writers?

Andrew Gudgel: I’m a big fan of aphorisms and mottoes, so I’ll keep it short:

- Nulla dies sine linea — Pliny (“No day without a line” i.e. write something every day.)

- Read as broadly as possible.

- If you try, you might fail. But if you never try, you’ve failed already.

- As long as it fits the guidelines, don’t self-reject a piece by not submitting it.

- Write, submit, repeat as necessary.

These are all the old saws, but there’s a reason they’re still around: they work.

Thanks, Andrew! All my readers will want to surf over to your website to learn more about you.

Poseidon’s Scribe

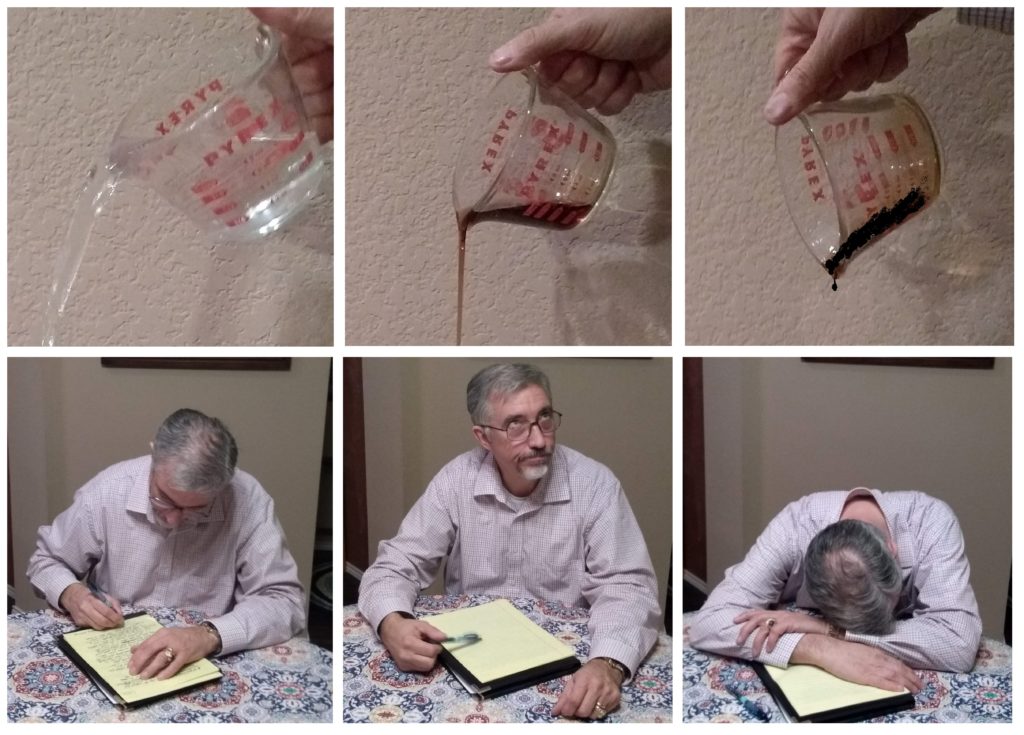

Author Andrew Gudgel and I were exchanging gifts at holiday time a few years ago. He’d been talking (for well over a year) about a story idea he had. I thought it was wonderful and kept urging him to write the story. Instead, as a gift to me, he said, “You write it.”

Author Andrew Gudgel and I were exchanging gifts at holiday time a few years ago. He’d been talking (for well over a year) about a story idea he had. I thought it was wonderful and kept urging him to write the story. Instead, as a gift to me, he said, “You write it.”

![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000039_00001]](https://stevenrsouthard.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/HidesTheDarkTower-DigitalCover-FINAL2-200x300.jpg)