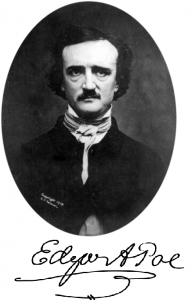

Ray Bradbury died June 5th of this year, a day this universe lost a literary giant. I just finished reading Something Wicked This Way Comes for the first time. I have read some other Bradbury works, including Fahrenheit 451, Dandelion Wine, The Illustrated Man, Now and Forever, and The Martian Chronicles. His short story “The Flying Machine,” in part, inspired my story “The Sea-Wagon of Yantai.”

I listened to the Recorded Books version performed by Paul Hecht, ©1962 by Bradbury, renewed 1997, and ©1999 by Recorded Books.

I listened to the Recorded Books version performed by Paul Hecht, ©1962 by Bradbury, renewed 1997, and ©1999 by Recorded Books.

The novel takes place in a Midwest town in the month of October sometime in the early to mid-1900s. A traveling carnival comes to the town and strange things happen, including the disappearance or alteration of some townspeople. Two boys and one of their fathers start to believe the carnival is evil and try to find a way to deal with the problem.

That synopsis sounds inexcusably bland, and doesn’t at all convey the magical experience of reading the book. Bradbury’s works are always poetic, alliterative, and metaphorical, and this novel is no exception. You find yourself swept along with the cadence of the words, caught up in whatever web Bradbury chooses to weave, and you’re glad of it.

The work deals with eternal themes of good and evil, as well as old and young. With the first, he examines the weapons wielded by forces evil and good. With the second, he explores the absurdity of the old wanting to be young and the young yearning to be old.

No one better expresses that delight, playfulness, curiosity, and sense of wonder of being a young boy in a Midwest town, than Ray Bradbury. I was once such a boy and can relate. The details he recalls and sensations he can–with lyrical prose–rekindle, resonate within me.

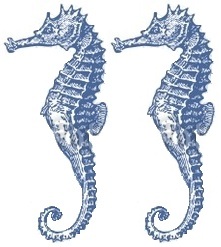

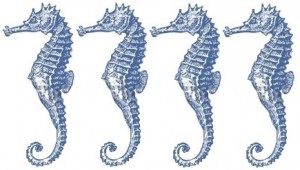

I’m not sure whether to classify the novel as horror or fantasy. Perhaps it’s a horror…poem? In any case, I loved it and give it my highest rating of 5 seahorses, the first work I’ve reviewed to have earned that rating. Do you disagree with my review? Leave a negative comment and you may find out “by the pricking of my thumbs, something wicked this way comes,” and that something is–

I’m not sure whether to classify the novel as horror or fantasy. Perhaps it’s a horror…poem? In any case, I loved it and give it my highest rating of 5 seahorses, the first work I’ve reviewed to have earned that rating. Do you disagree with my review? Leave a negative comment and you may find out “by the pricking of my thumbs, something wicked this way comes,” and that something is–

Poseidon’s Scribe