Many thanks to Charlotte Holley who tagged me to participate in The Next Big Thing blog hop. I didn’t know what a blog hop was but it seems like fun. In this one, authors answer questions about their Work in Progress (WIP) and people can follow the links along and see what various writers are working on. That way readers can anticipate and check back later to buy the books they’re interested in. It’s possible that one or more authors in this chain may really be working on The Next Big Thing!

When you’re tagged for this particular blog hop, you post your answers the following Wednesday and tag five other authors for the following Wednesday. Here are my answers:

1. What is the working title of your book? “A Tale More True”

2. Where did the idea come from for the book? If I recall correctly, I was thinking about fanciful trips to the Moon in early literature. I’m a fan of Jules Verne, but he’s actually a latecomer to that topic. While researching, I came across references to Baron Münchhausen. My story then sort of sprang into my head.

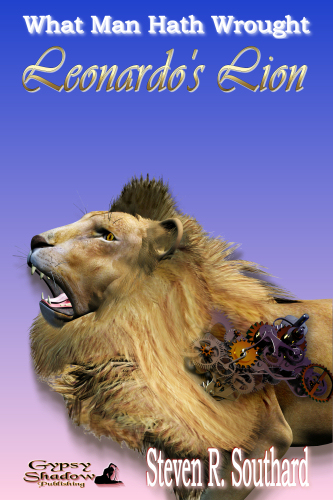

3. What genre does your book fall under? It’s alternate history, in the subgenre of clockpunk. I’ve not written much clockpunk, my story “Leonardo’s Lion” being the exception.

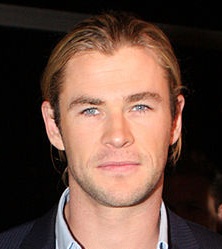

4. Which actors would you choose to play your characters in a movie rendition? There are three characters of interest. The protagonist is Count Eusebius Horst Siegwart von Federmann. Count  Federmann could be played well by actor Chris Hemsworth. He’d have to speak English with a German accent, but doesn’t have to do it well, since it’s a comedy. Count Federmann is a brooding character, angry at and jealous of Baron Münchhausen. The Count is intelligent, determined, and optimistic, but lacks sense.

Federmann could be played well by actor Chris Hemsworth. He’d have to speak English with a German accent, but doesn’t have to do it well, since it’s a comedy. Count Federmann is a brooding character, angry at and jealous of Baron Münchhausen. The Count is intelligent, determined, and optimistic, but lacks sense.

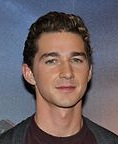

The Count has a young French servant named Fidèle, and I’ll select Shia LaBeouf for that role. Mr. LaBeouf would have to speak English with a French accent, but not an especially good one. Fidèle is full of life, but has the sense to fear danger, though he’s always respectful of nobility.

The Count has a young French servant named Fidèle, and I’ll select Shia LaBeouf for that role. Mr. LaBeouf would have to speak English with a French accent, but not an especially good one. Fidèle is full of life, but has the sense to fear danger, though he’s always respectful of nobility.

The character Baron Hieronymus Carl Friedrich von Münchhausen only appears briefly at the beginning and end of the story. Since it’s a cameo role, I’ll splurge and pick  Robin Williams. I need an older character of plain appearance who’s able to speak English with a German accent and captivate an audience with his words alone. Robin Williams played the part of the King of the Moon in the 1988 Movie “The Adventures of Baron Munchhausen.”

Robin Williams. I need an older character of plain appearance who’s able to speak English with a German accent and captivate an audience with his words alone. Robin Williams played the part of the King of the Moon in the 1988 Movie “The Adventures of Baron Munchhausen.”

5. What is the one-sentence synopsis of your book? A man is so angry about the self-aggrandizing lies of Baron Münchhausen that, just to prove the Baron wrong, he constructs a gigantic metal spring and launches himself to the Moon, where he learns about the nature of Truth.

6. Will your book be self-published or represented by an agency? I will offer it to Gypsy Shadow Publishing to be included in my What Man Hath Wrought series.

7. How long did it take you to write the first draft of your manuscript? I’m not done with the fist draft yet. I researched, planned, and outlined the story for about a month. First and second drafts will take another month.

8. What other books would you compare this story to within your genre? It’s a light-hearted clockpunk tale, so there aren’t many comparable stories. Perhaps the closest thing is that movie, “The Adventures of Baron Munchhausen.”

9. Who or What inspired you to write this book? The muse speaks. I listen and write it all down as fast as I can.

10. What else about your book might pique the reader’s interest? Come on—intense jealousy, a space voyage in 1769, and weird Moon creatures. What more do you want?

At this point I should mention which authors I’m tagging next in this blog hop, but I was unsuccessful in getting any to participate. I think the hop has been going for about thirty weeks now, with most authors tagging five others. If you do the math for such a chain, you’ll see how, theoretically, we’d pass the population of the earth in Week 15, and by Week 30 there would be over 2 with 20 zeroes participants.

There only seems to be that many budding authors in the world. So much for theory. As Yogi Berra said, “In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is.”

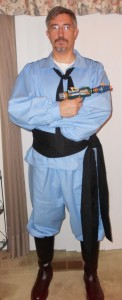

So I won’t be tagging anyone else. This strand of the chain ends here, with my alter ego, a guy I like to call—

Poseidon’s Scribe

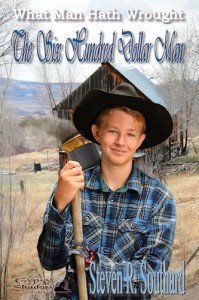

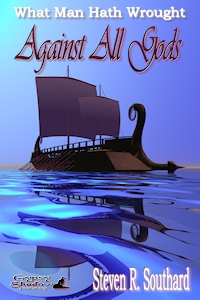

I just wanted to thank all of you who voted for my stories in the Critters Workshop Predators & Editors Readers Poll. The results for 2012 are in, and my story “The Six Hundred Dollar Man” came in 2nd out of 8 steampunk short stories. My story “Against All Gods” was tied for 4th in a list of 38 romance short stories. I feel so much gratitude for the amazing fans of—

I just wanted to thank all of you who voted for my stories in the Critters Workshop Predators & Editors Readers Poll. The results for 2012 are in, and my story “The Six Hundred Dollar Man” came in 2nd out of 8 steampunk short stories. My story “Against All Gods” was tied for 4th in a list of 38 romance short stories. I feel so much gratitude for the amazing fans of—

Back a year ago when I came up with this idea for a blog post topic, I figured I would have made a few short story promotional videos by this time. That didn’t happen, but lack of experience has never prevented me from having opinions. (In fact sometimes I have more to say about things I know less about!)

Back a year ago when I came up with this idea for a blog post topic, I figured I would have made a few short story promotional videos by this time. That didn’t happen, but lack of experience has never prevented me from having opinions. (In fact sometimes I have more to say about things I know less about!) Do you have what it takes to be a writer? If you did, would you know you did? Sometimes it’s difficult to tell. To make it easy for you, I’ve developed a handy test along the lines of Jeff Foxworthy’s ‘Redneck Test.’ See how many of these apply to you.

Do you have what it takes to be a writer? If you did, would you know you did? Sometimes it’s difficult to tell. To make it easy for you, I’ve developed a handy test along the lines of Jeff Foxworthy’s ‘Redneck Test.’ See how many of these apply to you. True, Leonardo da Vinci was an anatomist, architect, botanist, cartographer, engineer, geologist, inventor, mathematician, musician, painter, scientist, and sculptor. Arguably he was the greatest genius of all time. But…he never wrote fiction.

True, Leonardo da Vinci was an anatomist, architect, botanist, cartographer, engineer, geologist, inventor, mathematician, musician, painter, scientist, and sculptor. Arguably he was the greatest genius of all time. But…he never wrote fiction. In his book

In his book  At this point, I can’t resist a personal plug. Leonardo da Vinci is such a fascinating historical figure, I wrote a story about the mechanical automata lion he constructed for the King of France. Had that been all da Vinci did, it would have been achievement enough, far beyond the norm of the day, but it’s barely a footnote in any list of his accomplishments. My story,

At this point, I can’t resist a personal plug. Leonardo da Vinci is such a fascinating historical figure, I wrote a story about the mechanical automata lion he constructed for the King of France. Had that been all da Vinci did, it would have been achievement enough, far beyond the norm of the day, but it’s barely a footnote in any list of his accomplishments. My story,  experience is based solely on twenty years of being in small, amateur, face-to-face critique groups; not writing workshops, classes, or online critique groups; so the following advice is tuned to that sort of critique.

experience is based solely on twenty years of being in small, amateur, face-to-face critique groups; not writing workshops, classes, or online critique groups; so the following advice is tuned to that sort of critique. Federmann could be played well by actor Chris Hemsworth. He’d have to speak English with a German accent, but doesn’t have to do it well, since it’s a comedy. Count Federmann is a brooding character, angry at and jealous of Baron Münchhausen. The Count is intelligent, determined, and optimistic, but lacks sense.

Federmann could be played well by actor Chris Hemsworth. He’d have to speak English with a German accent, but doesn’t have to do it well, since it’s a comedy. Count Federmann is a brooding character, angry at and jealous of Baron Münchhausen. The Count is intelligent, determined, and optimistic, but lacks sense. The Count has a young French servant named Fidèle, and I’ll select Shia LaBeouf for that role. Mr. LaBeouf would have to speak English with a French accent, but not an especially good one. Fidèle is full of life, but has the sense to fear danger, though he’s always respectful of nobility.

The Count has a young French servant named Fidèle, and I’ll select Shia LaBeouf for that role. Mr. LaBeouf would have to speak English with a French accent, but not an especially good one. Fidèle is full of life, but has the sense to fear danger, though he’s always respectful of nobility. Robin Williams. I need an older character of plain appearance who’s able to speak English with a German accent and captivate an audience with his words alone. Robin Williams played the part of the King of the Moon in the 1988 Movie “

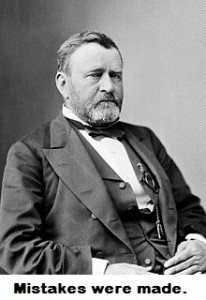

Robin Williams. I need an older character of plain appearance who’s able to speak English with a German accent and captivate an audience with his words alone. Robin Williams played the part of the King of the Moon in the 1988 Movie “ Among the worst passive sentences ever written is “Mistakes were made.” Politicians since Ulysses S. Grant have used that one to acknowledge a problem but to hide the responsible party from blame. However, the press and the public are on to that tactic, and would pounce on any official who uttered it (after laughing out loud).

Among the worst passive sentences ever written is “Mistakes were made.” Politicians since Ulysses S. Grant have used that one to acknowledge a problem but to hide the responsible party from blame. However, the press and the public are on to that tactic, and would pounce on any official who uttered it (after laughing out loud).