Many authors have pets. I thought I’d speculate why that’s so.

I did a little online research and came up with the following table of authors, their pet type and breed, and the pet name or names, if known. For the data in the table, I’m grateful to the bloggers here, here, and here.

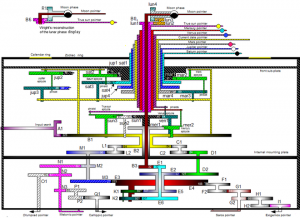

| Author | Pet Type-Breed | Pet Name(s) |

| Michel de Montaigne | Cat | |

| Samuel Johnson | Cat | Hodge |

| Elizabeth Barrett Browning | Dog – Cocker Spaniel | Flush |

| Edgar Allan Poe | Cat | Catterina |

| Charles Dickens | Bird – Raven | Grip |

| Jules Verne | Dog | Follet |

| Mark Twain | Cat | Bambino |

| Edith Wharton | Dogs | Mouton, Sprite, Mitou, Miza, Nicette, Mimi |

| Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette | Cat | |

| Gertrude Stein | Dog – Poodle | Basket |

| Hermann Hesse | Cat | |

| Virginia Woolf | Dog | Pinka |

| William Carlos Williams | Cats | |

| Raymond Chandler | Cat | Taki |

| T. S. Eliot | Cat | |

| Edith Södergran | Cats | Totti (favorite) |

| Dorothy Parker | Dog | Misty |

| Aldous Huxley | Cat | |

| William Faulkner | Dogs | |

| Jean Cocteau | Cat | |

| E.B. White | Dog – Dachshund | Minnie |

| Ernest Hemingway | Cats (23) | Snowball, Uncle Willie |

| Jorge Luis Borges | Cat | |

| John Steinbeck | Dog – Poodle | Charley |

| Jean Paul Sartre | Cat | |

| Wystan Hugh Auden | Cat | Rudimace |

| Tennessee Williams | Cat | Sabbath |

| William S. Burroughs | Cats | Fletch, Spooner, Ginger, Calico Jane, Rooski, Wimpy, Ed |

| Tove Jansson | Cat | |

| Julio Cortázar | Cat | Theodor W. Adorno |

| Doris May Lessing | Cats | El Magnifico |

| Charles Bukowski | Cat | |

| Ray Bradbury | Cat | |

| Patricia Highsmith | Cats and snails | |

| Jack Kerouac | Cat | Tyke |

| Kurt Vonnegut | Dog | Pumpkin |

| Truman Capote | Cat | |

| Edward Gorey | Cats | |

| Mary Flannery O’Connor | Peacocks (~40) | Manley Pointer, Joy/Hulga, Mary Grace |

| George Plimpton | Cat | Mr. Puss |

| Peter Matthiessen | Cat | |

| Maurice Sendak | Dog | Herman |

| Philip K. Dick | Cat | Magnificat |

| Jacques Derrida | Cat | |

| E.L. Doctorow | Dog | Becky |

| Joyce Carol Oates | Cat | |

| Stephen King | Cats and Dogs | Clovis (one of the cats) |

| Neil Gaiman | Cats | Coconut, Hermione, Pod, Zoe, Princess |

Obviously, the most common pets on the list are cats and dogs. However it’s notable that Charles Dickens had a raven; Patricia Highsmith kept snails; and Mary Flannery O’Connor make peacocks her pets.

Before conducting my research, I assumed authors would have clever or literary names for their pets. After all, they know how to choose words carefully. That’s why, in my table, I included pet names where known. However, for the most part, authors name their pets the same things most people do. Maurice Sendak named his dog for Herman Melville, but that’s the exception.

There are websites now for today’s authors to post entries about themselves and their pets—notably here, here, and here.

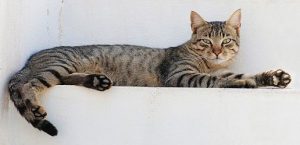

Why do authors keep pets? Likely for the same reason other people keep pets—companionship. Pets can serve other functions, of course. Dogs can protect a home or assist the blind. Cats can rid a home of mice.

Still, I think certain aspects of pet companionship appeal to authors in particular.

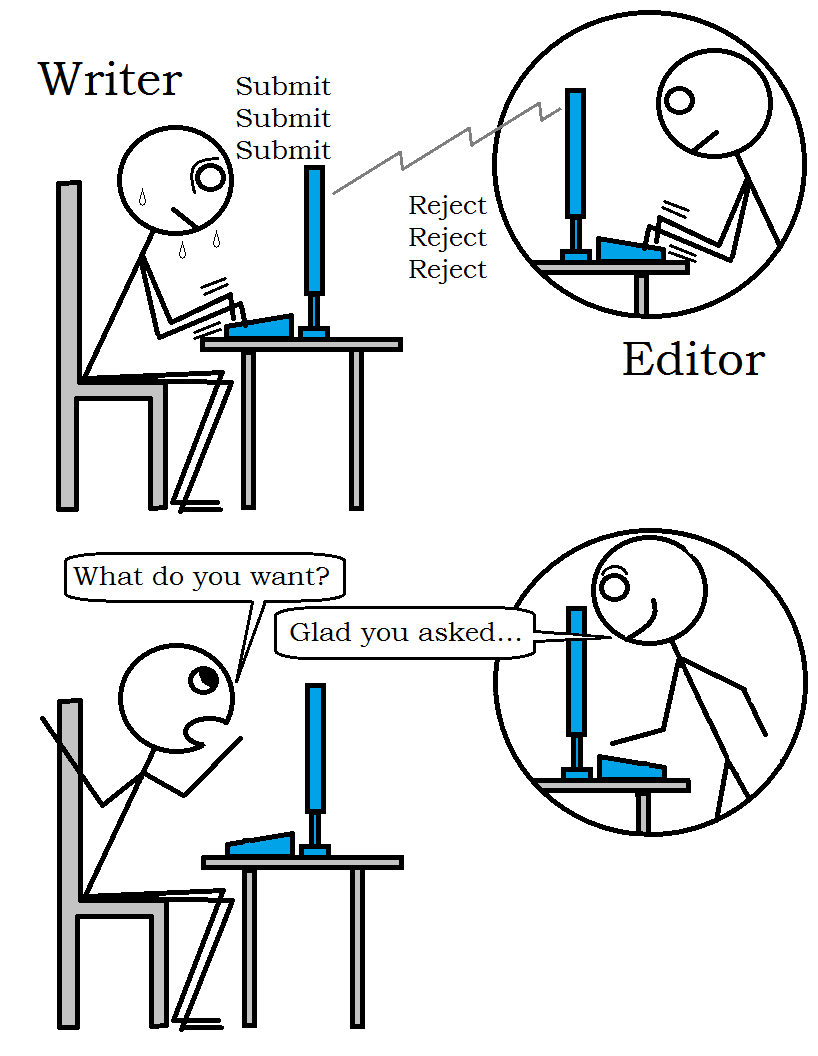

- Writers spend considerable time away from others, and prefer silence or soft instrumental music while writing. Human voices (even singing) can be a distraction. Pets will lie or sit quietly for long periods.

- A pet will provide a relaxing break from writing. Often the pet determines these intervals. But it’s thought animals may sense human emotions, and sometimes the pet might detect that the writer needs a break.

- A writer can use a pet as an unbiased and uncritical sounding board. A pet will listen patiently while being read to, and provide no feedback. The writer has the benefit of an audience, with no need to feel self-conscious about the poor quality of a first draft.

- A pet can serve as inspiration for a writer who is writing a story about a similar animal. The writer can observe a pet’s movements, habits, and general personality, and incorporate these in the story.

There must be other reasons as well, and I urge you to comment and offer some.

As for me, I do not have a pet. Some years ago, I kept several fish in a nice aquarium, but I gave that up. I’m allergic to animal hair, but some dogs and cats are hairless, so that’s not a real barrier. Who knows, someday a pet might offer its own special companionship to—

Poseidon’s Scribe

Sure, you say, but those great authors don’t do anything but write. Writing is their day job. That may be true for many of the great authors, but few of them started great. Most had day jobs until their books sold well.

Sure, you say, but those great authors don’t do anything but write. Writing is their day job. That may be true for many of the great authors, but few of them started great. Most had day jobs until their books sold well.

A website does at least the following things for you:

A website does at least the following things for you:

Your mind is filled with raw feelings, and you have no room for anything else. You can’t be creative, not now. You can’t get in the mind of a character right now, can’t be bothered with rules of English, or with choosing the right words. Besides, your novel is a comedy, and you’re feeling the opposite of funny.

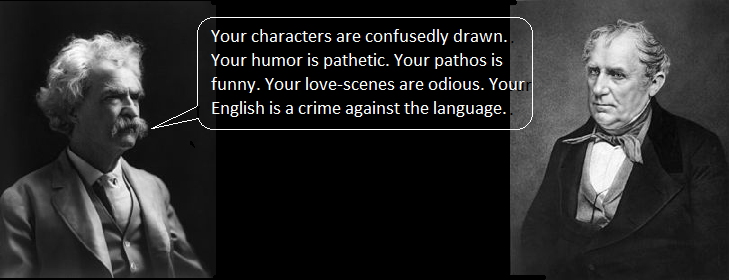

Your mind is filled with raw feelings, and you have no room for anything else. You can’t be creative, not now. You can’t get in the mind of a character right now, can’t be bothered with rules of English, or with choosing the right words. Besides, your novel is a comedy, and you’re feeling the opposite of funny. In Twain’s acerbic style, he starts by accusing three Cooper-praising reviewers of never having read the books. He then lays into Cooper, saying, “…in the restricted space of two-thirds of a page, Cooper has scored 114 offenses against literary art out of a possible 115. It breaks the record.” Twain asserts there are 19 or 22 rules “governing literary art in domain of romantic fiction” and says Cooper violated 18 of them. He lists those 18 rules.

In Twain’s acerbic style, he starts by accusing three Cooper-praising reviewers of never having read the books. He then lays into Cooper, saying, “…in the restricted space of two-thirds of a page, Cooper has scored 114 offenses against literary art out of a possible 115. It breaks the record.” Twain asserts there are 19 or 22 rules “governing literary art in domain of romantic fiction” and says Cooper violated 18 of them. He lists those 18 rules.