“Today’s blog post is about the word ‘said,’” said Poseidon’s Scribe.

“What is there to say about ‘said?’” asked Blog Reader, who hoped to write fiction someday.

“First, ‘said’ is the most common type of ‘dialogue tag’ used in fiction to indicate who’s speaking,” said the Scribe. “However, many budding authors worry about overusing that word, so they substitute other words.”

“I don’t believe that,” asserted the Reader.

“It’s true, but the fact is, ‘said’ is pretty much invisible. You can’t overuse it,” said the Scribe. “People pass right over it as they read.”

“Well, I declare,” declared the Reader.

“Still, there is something even worse than that,” said the Scribe.

“What’s that?” the Reader asked, questioningly.

“Modifying ‘said’ with an adverb.”

“I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that,” the Reader said unthinkingly.

“Use of adverbs in that way is termed a ‘Tom Swifty,’ from the Tom Swift series of books about a young inventor. The authors of those books occasionally sought to modify ‘said’ with adverbs. Not only are they examples of bad writing, but Tom Swifties have given rise to an entire brand of humor. There are examples here and here and here.”

“Use of adverbs in that way is termed a ‘Tom Swifty,’ from the Tom Swift series of books about a young inventor. The authors of those books occasionally sought to modify ‘said’ with adverbs. Not only are they examples of bad writing, but Tom Swifties have given rise to an entire brand of humor. There are examples here and here and here.”

“Okay, please stop listing links,” the Blog Reader said haltingly.

“Look, there are at least four things to remember about writing dialogue,” said the Scribe, “and the first is to be very clear about who’s talking. Don’t leave your readers wondering about that.”

“What do you mean?”

“If you go on for several lines of dialogue without tags–“

“Like we’re doing now, you mean?”

“–the reader can lose track of who’s speaking.”

“You don’t say.”

“I do. Especially when there’s more than two characters or when they have similar styles of speech.”

“Are there any times you would use several lines of untagged dialogue?”

“Oh, yes. That technique can heighten the drama of a scene, build it up to a climax. As each line of dialogue becomes shorter and shorter, your readers will naturally sense the tension building.”

“Are you sure about that?”

“Yes, I’m certain.”

“Really certain?”

“Oh, yes.”

“Sure?”

“Yup.”

“Okay, I think I understand that,” said the Blog Reader. “You said there are four key points about dialogue. What’s the next one?”

“Keep it interesting,” said Poseidon’s Scribe. “Humans are social animals and love to talk. Your readers want to hear your characters talking, and they have a preference for dialogue over narration. But they don’t want to be bored, so keep dialogue interesting.”

“And the third key point?”

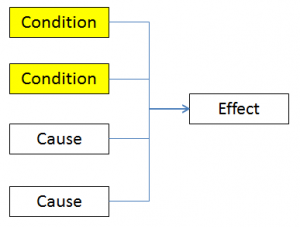

“I thought you’d never ask,” said the Scribe. “It’s related to the second point. Use dialogue for dramatic purposes, to show characters at their moments of strong emotion as they grapple with the problem that represents the story’s conflict. Minimize the use of dialogue just for providing information. That’s called info-dumping.”

“Which is what you’re doing now,” said the Reader.

“True, but we’re having a real discussion, not a fictional one.”

“Are you sure?”

“Pretty sure,” Poseidon’s Scribe held up his right index finger. “There’s one last point I want to make about the use of ‘said’ in dialogue. If you’re still worried about repeating ‘said’ and you doubt my point earlier about readers skipping over it, then substitute some type of action, or movement, or description.”

“What do you mean?” The Reader’s brows furrowed.

“Instead of using ‘said,’ have your character do something while speaking.” The Scribe swept his hand to indicate motion. “After all, people really do things while talking. They don’t just stand there.”

The Reader nodded. “I see what you mean. But what do I do if I have a question about this later?”

“Just click on ‘leave a comment’ below this blog entry. See it down there?”

“Yeah, there it is. Well, thanks for everything!” The Blog Reader smiled.

“Don’t mention it,” said–

Poseidon’s Scribe