Unlike writers of the past, we own computers to make our lives easier. But the machines arrived with plenty of baggage. Have they been worth it?

For most of human history, authors wrote by hand with a scribbling implement making marks with ink on some form of paper. (We’ll ignore the ages of chiseling into stone or making impressions on clay.) By the late 1800s, typewriters became commercially available. Only in the last forty years have writers turned to computers.

The Case for the Pen

Consider the ease and simplicity of pens or typewriters vs. computers. No passwords, no two-factor authentication, no need for backups, no pull-down menus, no need to pay for software updates, and no viruses. No chance of some hacker stealing your manuscript. No need to recharge or (except for electric typewriters), plug in to an outlet. Most of all, with pens or typewriters, there’s little to learn first—you just start writing.

The Case for the Computer

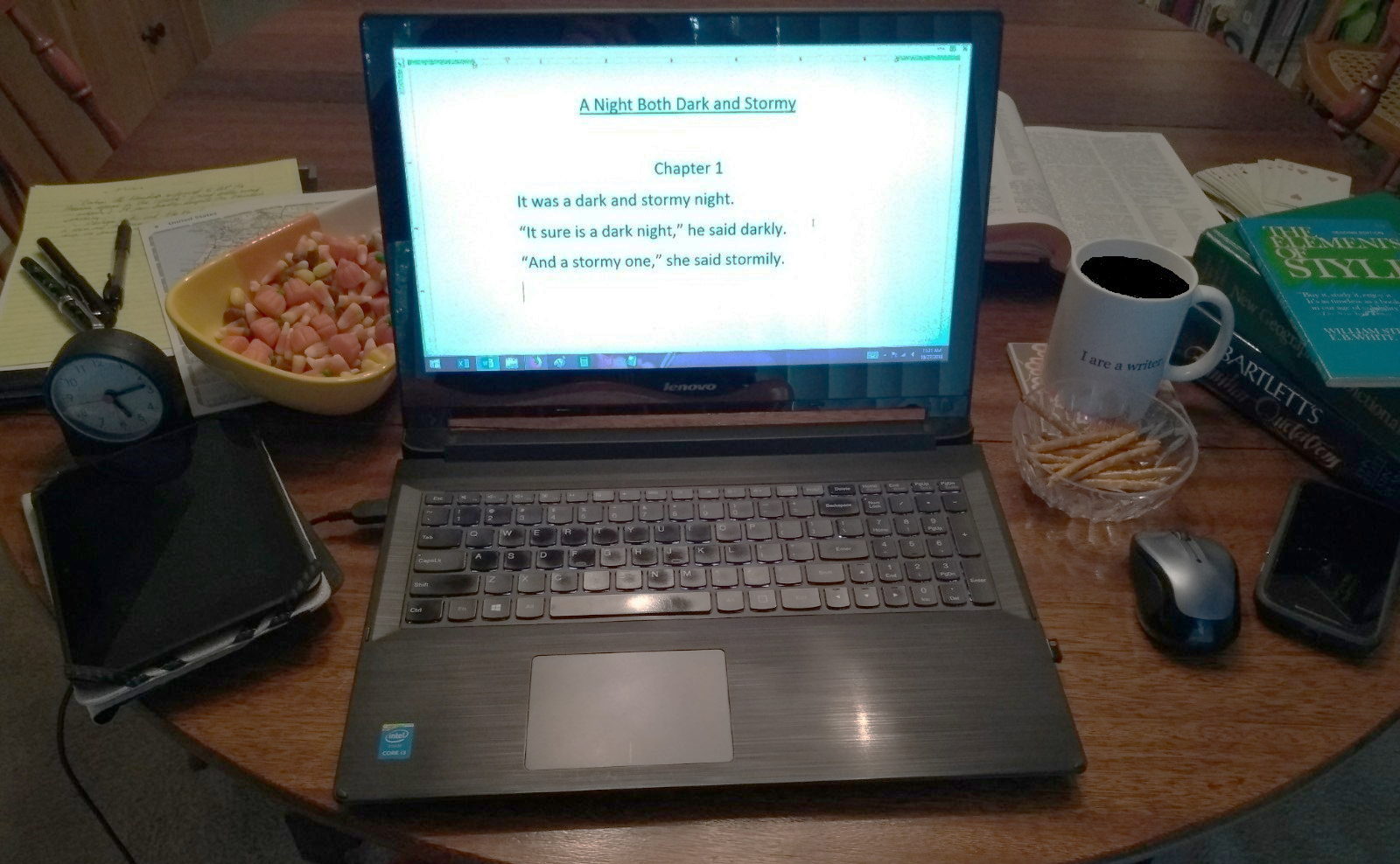

To be fair to computers, we’ve gained much in return, compared to previous methods. We see our text instantly, as it will appear in final form. That’s something. We’ve also swept away the piles of paper and books, the fire hazard that used to clutter a writer’s office. Also, we use the same computer for research, mostly eliminating the need to pore through dusty tomes for obscure facts. We can search through previously written text more easily than flipping through pages.

Side Benefits

Yes, I’m aware of studies showing increased brain activity when writing with pen and paper compared to using computer keyboards. But for purposes of this post, I don’t care about brain activity. I’m concerned with overall ease of use.

Summary

Computers render certain writing tasks easier—storing, retrieving, searching, and researching. Pens and typewriters ease other writing aspects—ready access, cost, learning, and security.

Decision

Like so many other facets of writing, different writers find their own methods easier. You must make this decision yourself. Sorry if this seems like a copout, but what’s true for you may not be true for—

Poseidon’s Scribe

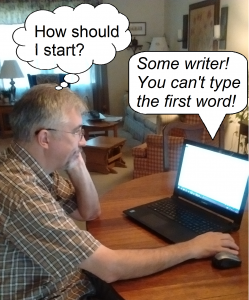

We live in a distraction-rich environment. Even before the Internet, there were rooms to clean, library books to return, lawns to mow, desk items to straighten, and windows to gaze through. Today, there are Facebook posts to like, tweets to retweet, texts to answer, online stores to shop in, blog posts to read, and new sites to explore.

We live in a distraction-rich environment. Even before the Internet, there were rooms to clean, library books to return, lawns to mow, desk items to straighten, and windows to gaze through. Today, there are Facebook posts to like, tweets to retweet, texts to answer, online stores to shop in, blog posts to read, and new sites to explore. You’ve been thinking about your story a long time, plotting it, developing the characters, working on the setting. You have notes, outlines, plot diagrams, and character descriptions up to here. Now it’s time to write, but no words are coming out.

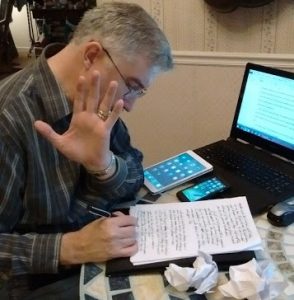

You’ve been thinking about your story a long time, plotting it, developing the characters, working on the setting. You have notes, outlines, plot diagrams, and character descriptions up to here. Now it’s time to write, but no words are coming out. I don’t write there very much anymore. Now I write first drafts while commuting on the subway.

I don’t write there very much anymore. Now I write first drafts while commuting on the subway. on the couch in the living room. In good weather, I sometimes write out on the deck.

on the couch in the living room. In good weather, I sometimes write out on the deck.