You’re stuck. You’ve written your character into a plot hole. Or you’re not sure where to go next with the story. Or you can’t decide on a setting or character name. The late Steve Jobs of Apple has a method of solving your problem.

The Problem

You’re determined to write the story. The flame within you still burns, but it’s sputtering. Whatever form the roadblock takes, you can’t seem to drive past it. You’ve sat for ten minutes focused on the problem, but you’re getting nowhere and feeling frustrated.

The Solution

According to this article in Inc. by Jessica Stillman, Steve Jobs used to get stuck as well, though not while writing fiction. Even so, his technique works for writers, too. If you’re stuck after ten minutes of trying, stop working and take a walk.

That’s it. Rise from the chair and go for a walk. Preferably outside.

Chances are, you’ll come up with a solution to the story problem while strolling. Either that, or when you return to pen or keyboard, you may find yourself in a better frame of mind to attack the problem.

Why it Works

Stillman’s article discusses research conducted by neuroscientist Mithu Storoni that helps explain the science behind this. Often, we get stuck because we focus too much on the problem and on traditional solutions. We need a way to open our mind to more creative ideas. We need a looser mental state.

That requires a mental nudge, the kind a walk can provide. While walking, you’re less focused on the problem. Your brain must busy itself with other things—directing footsteps, sensing for hazards, perhaps even just enjoying the day. That puts your brain in the “loose” state necessary for creative problem-solving, for innovative idea generation.

It’s All Connected

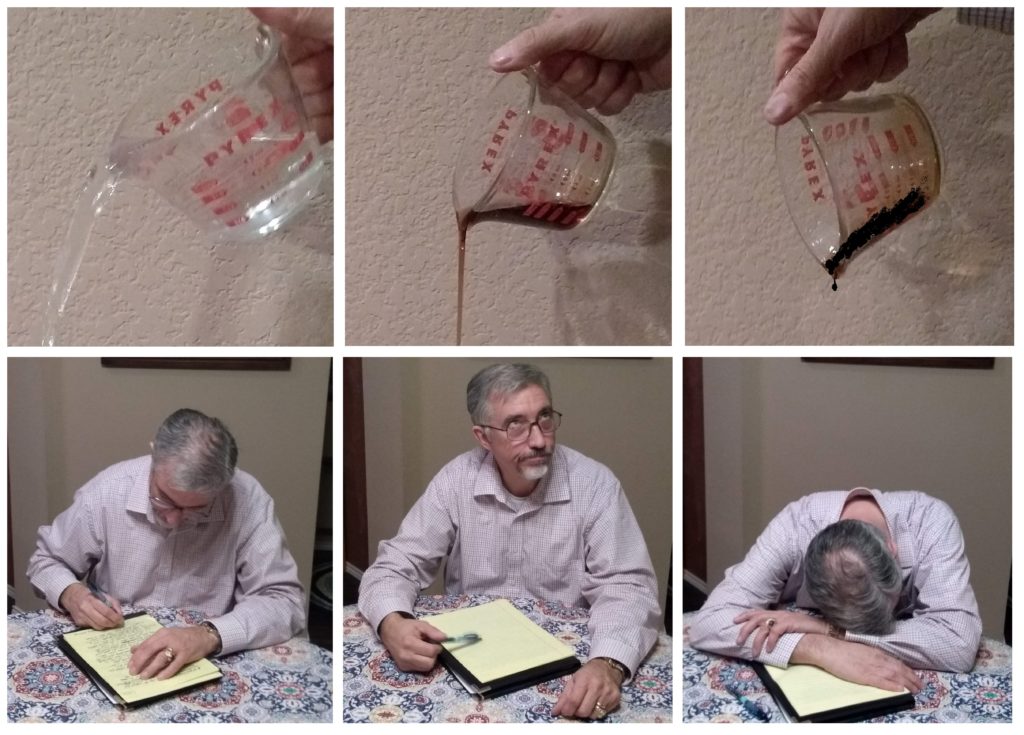

Steve Jobs’ simple advice parallels the idea of the Pomodoro Technique, which I’ve blogged about before. That technique involves focused work for twenty-five minutes followed by a five-minute break. The break clears the mind, readying you for the next twenty-five-minute focus session.

If you’re able to take your walk outside, you’ll get benefits spelled out in Good Energy: The Surprising Connection Between Metabolism and Limitless Health, by Dr. Casey Means. She advocates frequent outdoor activities as a way toward better health.

If a brief walk helps to get your writing flowing again after being stuck, remember to send a thank-you thought toward Steve Jobs and—

Poseidon’s Scribe