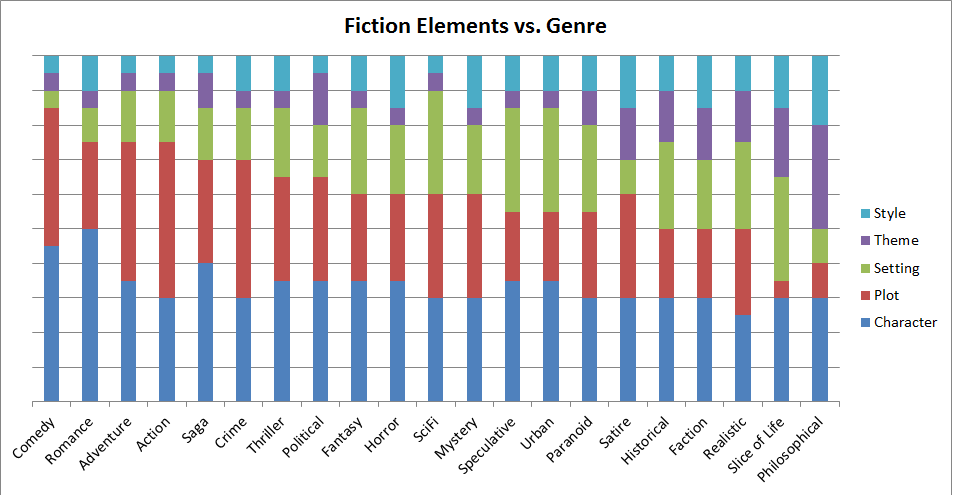

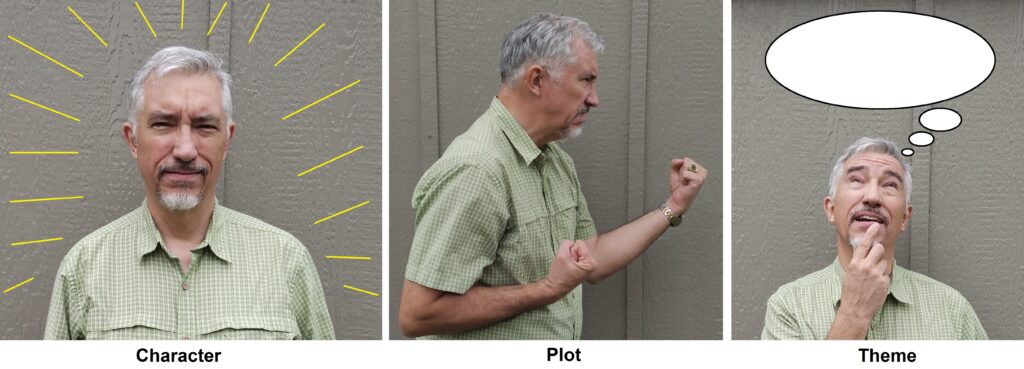

You’re thinking about writing a novel. Do your first thoughts focus on a character, events, or ideas? Whichever it is, opportunities and dangers await you.

This past week, I listened to an online lecture by author Emily Colin on the subject of “Hooking Readers and Publishers with Your Opening Pages and Never Letting Go.” She mentioned these three types of starting points, and that got me thinking.

I discovered a post by author PJ Parrish dealing with two of the three—character and plot. She listed strengths and challenges associated with each mindset. Using her post as a starting point, I’ll present my own list of pros and cons for all three.

Character-Based

Your first question is, “Who?” and you imagine a character, or more than one, fully formed, with backstory, personality, and appearance all locked in. Your character is like family to you.

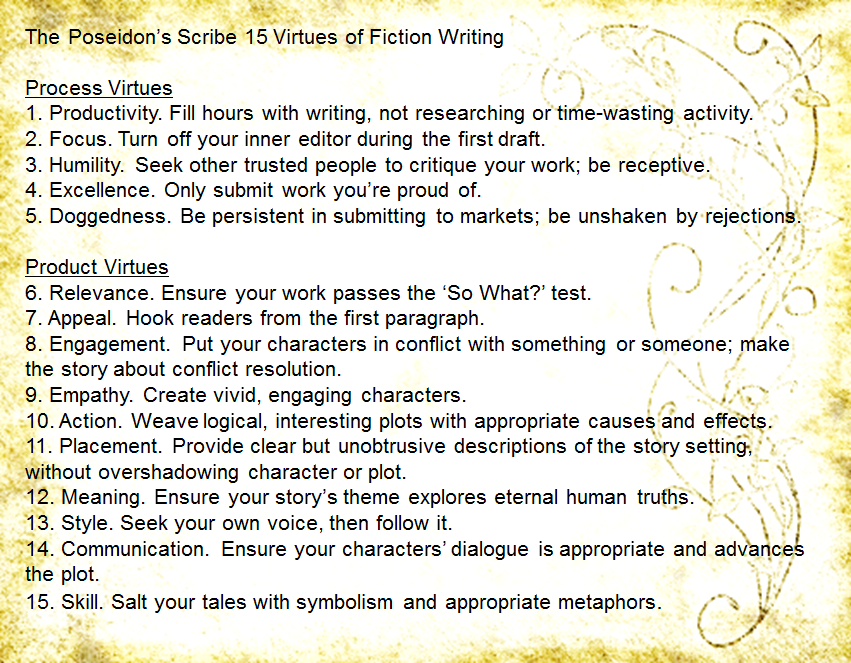

Pros:

- Reader Empathy. People care about characters, and if yours are interesting and well-drawn, your novel will entrance readers.

- Writer Empathy. You know your character so well, you’ll have no problems writing actions, behavior, and dialogue at any point. You’ll know the character’s appropriate action in, and reaction to, any situation.

- Editor Empathy. Character-driven stories dominate the fiction market now. A story with engaging characters may be easier to sell.

Cons:

- Idolizing. If you fall in love with your character, you may see no flaws, and therefore no change will result, no learning will occur.

- Meandering. If your plot is weak, events may seem disconnected or illogical. The plot may seem contrived, with scenes designed to showcase the character instead of presenting a series of increasingly difficult challenges.

- Puzzling. If you neglect theme, readers might like your character, but be left wondering what the book was all about, and why they should care.

Plot-Based

Your first question is, “What if?” and you imagine the conflict, the journey, the rising and falling tension, the escalation of stakes, and the resolution.

Pros:

- Blurb. You know your back cover blurb already, as well as the story outline and synopsis. A ready blurb makes the story marketable.

- Suspense. The thing that keeps readers reading on—suspense—comes easy to you. You’ve lined up the twists that keep readers surprised.

- Structure. The writing may go easier for you, since you know where the story’s going.

Cons:

- Unsurprising. If you adhere to your plot outline too rigidly, the ending might be predictable. Or you might force a character to act out-of-character, because it’s necessary to your plot.

- Boring. In peopling your plot, you may end up with characters who are flat, uninteresting, even stereotyped.

- Puzzling. If you neglect theme, readers might like your plot, but be left wondering what the book was all about, and why they should care.

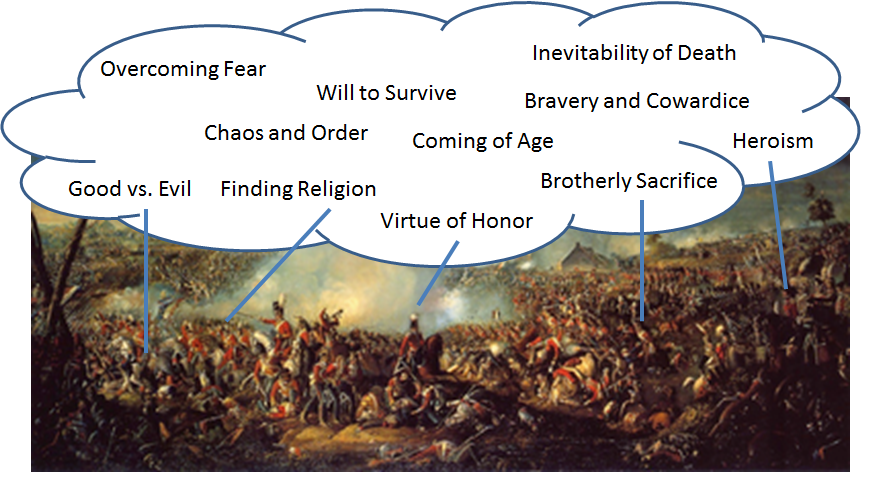

Theme-Based

Your first question is, “What’s the point?” You have something to say to the world. You’d like to persuade, to bring about change. You feel deeply about a message you want to convey.

Pros:

- Elevation. Strong themes, well expressed, can raise a book above common genre books into the realm of literary fiction.

- Double-Take. Books with strong themes make readers think. Only later do they realize the power of the message, and that makes them love the book even more than when they first finished it. Such books can change lives.

- Endurance. Well-written stories that say something true and eternal about the human condition can become classics.

Cons:

- Preaching. If you beat your fist on the pulpit too strongly, the reader will walk out on your sermon. If you can’t weave themes into your fiction with subtlety, write a textbook instead.

- Forcing. Readers will sense when you’ve engineered your plot to make your larger point, especially if effects don’t follow from causes.

- Over-Simplifying. If your characters lack dimension, if they can be summed up in one word, if their purpose is just to symbolize an idea in support of your theme, they’re not realistic.

In summary, it’s okay if you’re any one of the three types of writers. (I’m plot-based.) Strive to recognize your tendency and compensate for the cons associated with your type. Think about the other two aspects as you write and shore up those areas you’re weak in.

Interesting bonus fact: if you rearrange the letters in the words “character,” “plot,” and “theme,” you cannot come up with the words—

Poseidon’s Scribe