We’ll consider story and craft first, then relate them to a cow pasture.

Impetus

I read Craft in the Real World by Matthew Salesses, hoping to learn to become a better writer. The book’s second half helped with that. The first half, which I read first, differed. It enumerated a list of grievances with a writers’ workshop that the author attended.

To understand the gist of his complaint, let’s start with definitions.

Story

For our purposes, let us define a ‘story’ in broad enough terms to encompass all human cultures across all human history. We could say a story is a text narrative featuring one or more characters in one or more settings, in the course of which, one or more events occur.

Craft

Craft, we’ll say, is the way a writer writes a story. It includes the techniques the writer employs, the story aspects the writer emphasizes, the words the writer chooses, etc.

The Universal and the Particular

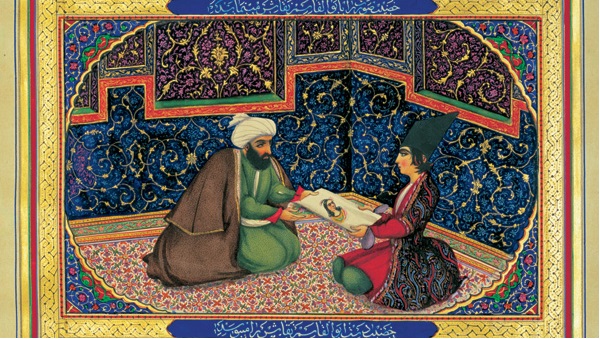

We’ve defined ‘story’ in a universal manner so it includes campfire tales told by prehistoric tribes, Gilgamesh, The Story of Tambuka, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, and King Lear. ‘Craft,’ by contrast, varies across cultures and time periods. A particular technique, word cadence, or plot structure might resonate in one country but not another, one century and not another.

Controversy

A difficulty might arise when a writers’ workshop or Master of Fine Arts (MFA) course teaches craft suited to its culture, but a student accustomed to another culture’s craft attends.

That occurred when Matthew Salesses, a Korean-American, attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. To him, the workshop seemed too prescriptive, too intolerant of other approaches.

My Take

Never having attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, I can neither validate nor dismiss Salesses’ experience. That workshop, founded in 1936, produced graduates who went on to earn Pulitzer Prizes, Booker Prizes, National Humanities Medals, and MacArthur Fellowships. Five graduates went on to become U.S. Poets Laureate.

Matthew Salesses has written six books and dozens of essays, been named one of thirty-two Essential Asian American Writers, and received multiple awards and fellowships for his writing. He runs his own graduate-level workshops in creative writing.

Perhaps the Iowa Writers’ Workshop had been teaching craft suited for modern-day tastes of U.S. readers. Perhaps Salesses found that approach too rigid and inflexible, based on his experience with Korean literature. If so, his dissatisfaction appears understandable, despite the success and staying power of the workshop.

As I’ve noted, though, craft changes, often based on reader whims and sudden fads. A given formula works well for a while, then readers tire of it and it becomes stale. A different kind of novel catches on, perhaps one from a foreign country, or one written in a foreign style, or a nostalgic return to a previous style from long ago. Other authors then write in that vein to capitalize on the trend, to catch the wave. In time, that style fades in its turn, soon replaced by another.

Why do these fads, these literary waves, occur? The fickle nature of readers doesn’t explain it all. I suspect some influential readers, eager to experience fresh books, seek something unusual, find it, and enjoy its newness. They see beyond craft to the underlying story. They spread the word, sparking a trend.

The Cow Pasture

Permit me a silly, Iowa-based simile. Think of story as a cow pasture, one of vast size with grass growing in every acre. Readers are the cows, gathering to devour grass/stories in a particular area. We’ll call that particular patch of grass the craft. In time, the cows consume the grass in that place, and have deposited cow-pies there, rendering that grass less desirable.

One cow moves on, finds a fresh patch with tall, tasty grass and begins munching there. Other cows notice and join the loner.

The process continues, cows moving from zone to zone. They drop fertilizer as they go, so previously grazed parts grow and become fresh again later.

Takeaway

Writers generate stories. They grow the grass, but don’t control the cows. Writers can create stories using currently successful craft. Or they can write stories outside that craft and hope a straying cow notices and draws the herd. A writer might dislike the popular and crowded area, and might fume that his favored grass zone attracts no cows. But cows go where they go.

Hey, cows! Over here! The tastiest grass is grown by—

Poseidon’s Scribe

Since humorous writing is so tough to get right, why don’t we forget the whole thing? For one, if we can manage to tell a funny story, readers like it. An amusing tale lifts them from the gloomy tedium of their dreary lives, the poor things. Think of it as a public service, kind of a ‘clown-author saves the world’ idea.

Since humorous writing is so tough to get right, why don’t we forget the whole thing? For one, if we can manage to tell a funny story, readers like it. An amusing tale lifts them from the gloomy tedium of their dreary lives, the poor things. Think of it as a public service, kind of a ‘clown-author saves the world’ idea. Violent interactions can take many forms beyond individual combat. These include war, rape, terror, shooting sprees, etc. This post focuses on fights between two characters, but many of my suggestions apply to other situations.

Violent interactions can take many forms beyond individual combat. These include war, rape, terror, shooting sprees, etc. This post focuses on fights between two characters, but many of my suggestions apply to other situations.

Advance warning: this post is full of opinions that may sound stereotypical and sexist. As a caveat, let me say the characteristics I’ll ascribe to women and men are generalizations. Not all men, nor all women, are as described below. There is plenty of overlap in thoughts and behaviors between genders.

Advance warning: this post is full of opinions that may sound stereotypical and sexist. As a caveat, let me say the characteristics I’ll ascribe to women and men are generalizations. Not all men, nor all women, are as described below. There is plenty of overlap in thoughts and behaviors between genders.