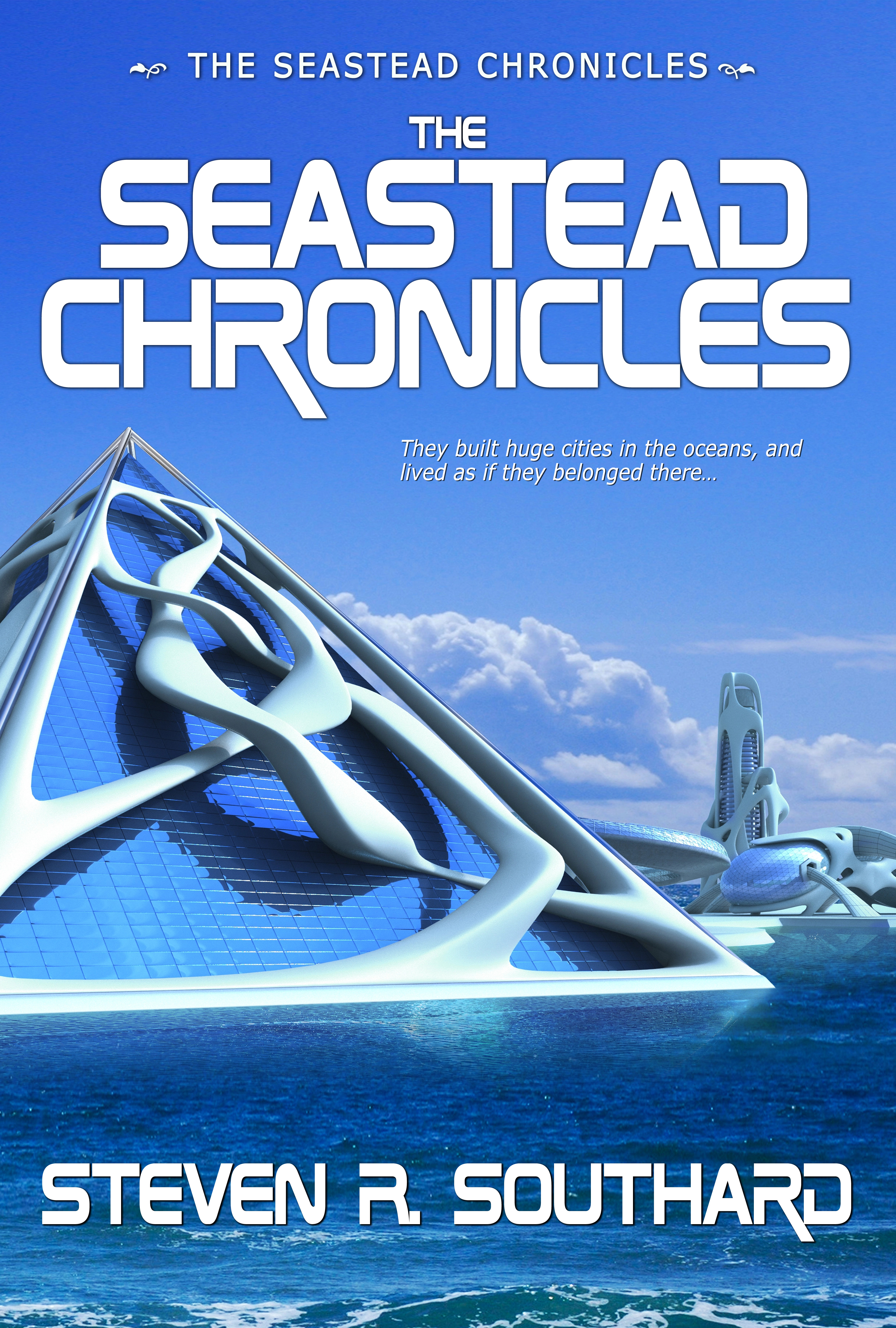

What comes after Rock? In my book The Seastead Chronicles, you’ll find a story about the next sound, the coming musical wave.

The world of The Seastead Chronicles shows much of humanity abandoning the land to live in cities on and under the sea. That new environment shapes them and gives rise to new art, new jargon, a new religion. And new music.

Liquisic

They call it liquid music, or liquisic. I introduce it in my story, “Deep Currents.” Like rock, liquisic employs syncopation. Unlike rock’s typical 4/4 rhythm, liquisic uses 6/8. This gives songs a rolling, undulating feel, like waves at sea.

Where rock often features a strong melody and background harmony, liquisic intertwines several equal melodies. This mimics the overlapping nature of ocean waves. No single melody predominates, and all blend harmoniously. Music theory experts might call it counterpoint, or contrapuntal.

Instruments

Liquisic instruments use water to achieve an ethereal, fluid sound. Some of the instruments exist now, and one awaits invention.

The hydraulophone sounds and works like a pipe organ, but uses water rather than air.

The glass armonica takes the sound you make when rubbing a wet finger around a wine glass, and expands the idea to a full “keyboard.” You get haunting, mysterious tones.

As for the fluidrum, I made up the name, but water-based drums exist in Africa, Asia, and among Native American tribes. Germans gave it a different name, the wassertrommel. In India, they play the Jal Tarang. Whatever fluidrums are, they provide rhythm for the liquisic group.

The aquatar might serve as the star of the group, but I have no idea what it looks like, how it works, or what it sounds like. I leave that for readers to imagine. Perhaps the strings stretch within flexible, water-filled membranes. A player would strum them with fingers, not picks. Maybe you could see through the aquatar’s transparent body to the colored water sloshing around inside, with lights illuminating it.

Your Turn

There. I’ve done the hard work—naming the music genre, coming up with its characteristics, and proposing the instruments. All you have to do is get a band together, practice, do some concerts, and make your fortune. My story “Deep Currents” in The Seastead Chronicles offers a name for your band and several ideas for song titles.

One more thing. After you hit it big with liquisic, show a little love to—

Poseidon’s Scribe