Today we’ll

consider the character Ned Land in Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under

the Sea.

Before doing so, I’d like to remind you to submit a short story to Twenty Thousand Leagues Remembered, an anthology I’m co-editing along with the creative and capable Kelly A. Harmon of Pole to Pole Publishing. We’re open for submissions and accepting stories as we go, and this publisher’s previous anthologies have all filled up before their closing dates. Therefore, don’t wait until the official closing date of April 30. Submit your story here.

Turning now to

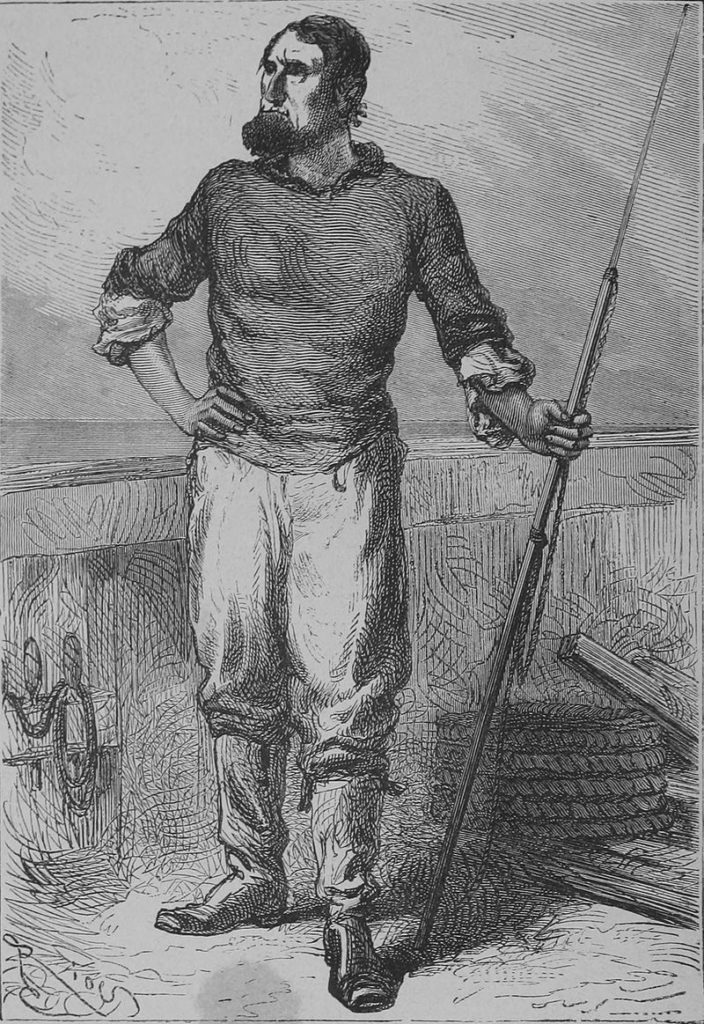

Ned Land, Verne introduces him as a Canadian harpooner from Quebec assigned to the

frigate USS Abraham Lincoln to assist the crew in hunting a menacing sea creature.

Verne has fun with this character’s name. In French editions, it is rendered as “Land,” the same as in English translations, not the French word for land, “terre.” Verne’s audience would have had to know the English word to get his pun. Ned is a man of the sea named for the land, who craves to escape from under the sea and eat food of the land.

Between Professor

Aronnax and Ned Land, readers come to understand two opposing ways of dealing with

their imprisonment aboard the Nautilus. The pair are opposites, with Aronnax’s

servant Conseil serving as the median. On several spectra, the two men occupy extreme

ends.

Ned Land is the

‘physical’ to Aronnax’s ‘intellectual.’ Land is often depicted as taking action,

while Aronnax observes and deliberates. It is Ned who throws the harpoon, who assaults

a steward, who goes ashore and shoots birds and kangaroos, who grabs the electrified

railing, who kills a shark, who harpoons a dugong, and who joins in the attack

on the giant squid, who tries to signal a nearby ship, and who arranges their escape

from the Nautilus.

Further, Ned

Land acts without thinking, while Aronnax thinks without acting. Often, Ned acts

impulsively, sometimes with a bad result but sometimes heroically. Aronnax suffers

from ‘paralysis by analysis,’ knowing what he should do, but not doing anything

about it.

Land represents

the common man in contrast to Aronnax, the upper-class gentleman. Aronnax eats

with Nemo and bunks in a room next to the Captain’s. Ned bunks and eats with

Conseil in the midships area reserved for the crew. Ned speaks plainly, occasionally

joking, while Aronnax speaks like a professor throughout.

The last facet

of their contrast is what I’d term the ‘man of nature’ vs. the civilized man.

Ned’s comfort zone is the out-of-doors, in the wild, killing and preparing his

own dinner. For his part, Aronnax would be lost without his servant and is more

at home in drawing rooms and eating gourmet food. Here, most of Verne’s audience

would identify closer with the professor, but nonetheless be fascinated by the harpooner.

Given their differing

viewpoints, it’s no wonder Aronnax sees the Nautilus as a vessel of underwater exploration,

while Land sees only a prison. Aronnax sees Captain Nemo as a rational engineer

and scientist, while Land sees him as an insane pirate and jailer.

Although the two share the same goal, leaving the Nautilus, they differ on timeframe and method. Aronnax would like to leave someday, after persuading a captain he sees as reasonable. Land wants to get off the submarine immediately, by force if necessary.

Verne resolves

this conflict in a draw. The trio departs the Nautilus far later than Ned would

have liked, after spending seven months aboard. However, they must sneak off

the ship without the Captain’s permission, during an emergency, and with Ned

guiding.

Ned Land, then,

is the perfect ‘friendly opposition’ to Pierre Aronnax, giving the novel

dramatic tension throughout. Have you ever known someone like Ned Land (except for

his harpooner occupation, of course)? A few like him have been known to—

Poseidon’s Scribe