You’ll enjoy reading my interview with an author whose debut novel just got published. A mutual friend and former submariner introduced me to my guest today, M. W. Kelly, a writer who also spent a lot of time beneath the waves.

M. W. Kelly became hooked on science after Neil Armstrong took an epic stroll one Sunday morning in July 1969. He later served as a submarine officer based in Scotland and New England. He is a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, Bryant University, and Swinburne University. After leaving the Navy, he spent two decades teaching college physics and astronomy. A member of Rocky Mountain Fiction Writers (RMFW) and the Hawai’i Writers Guild, Kelly loves reading and writing mind-bending literature. As a flight instructor, he has also published a column on flying among the Hawaiian Islands. He lives with his wife, Patty, in Colorado, and they spend their summers in Hawai’i.

Let’s dive into

the interview…

Poseidon’s

Scribe: How did you get

started writing? What prompted you?

M. W. Kelly: My father was a writer and instilled

the importance of writing every day. I started with short stories just for fun.

The short form is a great way to force yourself to craft a story that’s both

concise and intriguing. I think the skills you practice writing short stories

apply equally well to novels.

P.S.: Who are some of your influences? What

are a few of your favorite books?

M.W.K.: I grew up reading the classics by A.C. Clarke, Isaac Asimov, and Philip K. Dick. I really enjoyed hard science fiction best. The engineer in me craved cool technology, and the science geek in me demanded realism. After reading PKD’s books, I fell in love with speculative fiction having a strong character arc. This probably influenced my writing more than anything else. I just finished Ian McEwan’s latest book, Machines Like Me. It’s a wonderfully written example of character-driven science fiction. Fans of PKD’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (aka. Blade Runner) will love it. It’s thought provoking and raises questions about the limits of machine logic and moral decision-making.

P.S.: Give us the elevator pitch about your new novel, Mauna Kea Rising (Lost in the Multiverse).

M.W.K.: My readers tell me that Mauna Kea Rising is science fiction for people who hate science fiction. In the tradition of Ursula Le Guin and Margaret Atwood, character comes first, and science only adds spice to the hero’s journey. It’s set in a parallel world where the British Hawaiian Islands sit between rival superpowers, Japan and the UK. A single mother takes her son on a sailing voyage to Hawai’i, hoping to recapture the bond they once shared. Isolated at sea, the boat’s crew is unaware of a catastrophic solar flare. Throughout the Pacific, power grids fail. Cities plunge into darkness.

P.S.: Where did you get the idea for this

novel, and the eventual series?

M.W.K.: The story’s premise came to me from years of teaching college astronomy, covering strange apocalyptic possibilities such as supernovae, asteroid strikes, and solar flares. One of my students joked that a better name for my course would be “Death by Astronomy.” But seriously, as we come to depend more on technology in everyday life, many solar astronomers warn us that a powerful solar storm could wreak widespread damage to our modern power grids. It only takes a temporary blackout to remind us how much we depend upon a continuous and reliable source for electricity. Think back to the last time your power went out, then imagine living like that for a year or longer. The people of Puerto Rico have had to endure this hardship for over twenty months. How did they do it? They adapted to simpler lifestyles and relied on each other for community support, but it’s a difficult struggle and over three thousand people perished.

The story’s setting came from my annual trips to Hawai’i. I fell in love with the aloha spirit and grew a deep respect for their self-sustaining way of life. The state is a leading developer of wind, solar, and geothermal power technology. Three years ago, the governor signed a bill directing the state’s power utilities to generate all their electricity from renewable energy resources by 2045.

P.S.: How is the parallel universe of your novel different from our own?

M.W.K.: The parallel world found in the novel

differs in social-economic ways. America with only 48 states is akin to

Switzerland, preferring to stay out of foreign affairs. Russia and China have

lost world prominence after the Second Sino-Japanese War. Hitler never rose to

power, and the Second World War never came about. Japan and the United Kingdom

are superpowers where Britain rules the seas, and Japan explores the solar

system. Hawaii-50 is now the British

Hawaiian Islands, a member of the (UK) Commonwealth of Nations.

P.S.: Was there a point of divergence from

our universe, and if so, what was it?

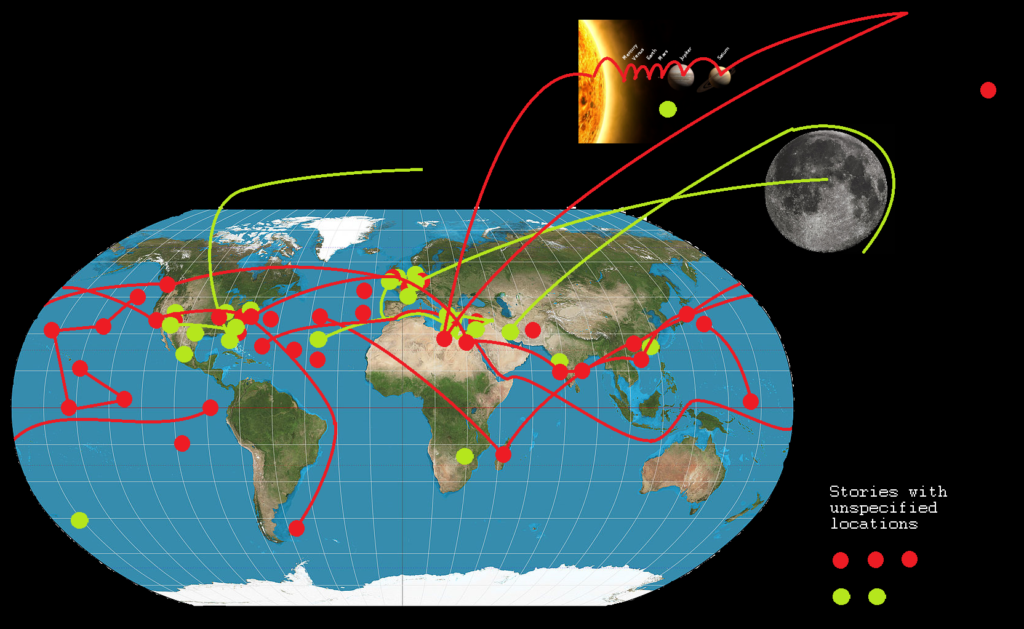

M.W.K.: The setting for my series grew out of the Many-Worlds Interpretation of quantum mechanics. The American physicist Hugh Everett first proposed every possibility embodied in Schrödinger’s probability waves is realized in one of a vast landscape of an infinite number of universes. The quantum multiverse creates a new universe when a diversion in events occurs, known as a “branch-point.” Whenever we decide upon some action, we create a branch-point in our timeline. Say you flip a coin. While it’s in the air, it has two possible future states: heads and tails. When you observe the outcome, you might see heads, but tails also exists—unobserved in a parallel world. In this way, a different universe branches from the previous one, creating a new world timeline. One copy of us sees heads, and another copy sees tails. Without giving too much away, each of the main characters in each book creates a branch-point where Earth’s world-timeline diverges. The Earth on which we live continues on, but now we have parallel, slightly different copies of our world.

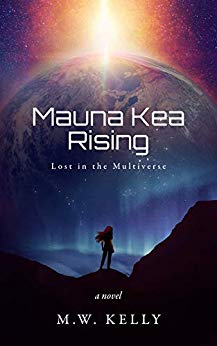

P.S.: The cover image for Mauna Kea Rising is striking, very eye catching. Can you tell us about the image and how it relates to the novel?

M.W.K.: Thank you. I think the book cover

turned out well because of the help many people gave me. After searching for

months, I found a graphic artist in Germany whose covers jelled with my vision.

She created a cover design that touched on two of the book’s major aspects: the

solar storm and a strong female protagonist. After a few designs, I tested

sample covers with about a dozen readers. Some were the book’s beta readers,

others were science fiction fans. For those who hadn’t read an earlier draft, I

provided a blurb or synopsis, so they knew the book’s premise. After getting

their impressions, I finalized the book design.

P.S.: Your story involves the immediate

aftermath of a civilization-destroying event. In what ways does your book

differ from other post-apocalyptic novels?

M.W.K.: Unlike many apocalyptic thrillers, the book is an adventure story where an eclectic band of friends (a Celtic engineer, Polynesian navigator, and Hawaiian Buddhist) rebuild their lives after an epic solar storm hits Earth. Fans of Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven will appreciate this approach. Like I mentioned earlier, the story centers on a community working together to adjust to life without the power grid. Sorry, no zombies here.

P.S.: It seems you’ve incorporated several

aspects of your life into the novel (being a former submariner, teaching

physics and astronomy, being a flight instructor, traveling between Colorado

and Hawai’i). How did you strike the balance between getting the details right

and getting too technical?

M.W.K.: That was hard to do. I imagine your

own experience as a submariner reflects this. Back on the boat, it seemed we

laced our every utterance with buzz-words. And oh, those acronyms! I think the

problem facing guys like us is we are too close to the technology. We may be

unaware of what our readers don’t know. That’s where beta readers are

invaluable. I carefully chose my reader pool, looking for people from different

backgrounds, races, and genders.

P.S.: Yes, it’s a challenge for me, too. What are the easiest, and the most difficult, aspects of writing for you?

M.W.K.: The easiest part of writing a novel is

researching and outlining. I guess it’s because these steps come naturally to

me after having spent my life in academic research and problem solving.

Outlining is also the most fun. Starting with a clean slate is exciting.

Everything is possible. The most difficult part is editing, and that’s where I

spend most of my time. I work with a dense checklist that would make Admiral

Rickover smile. Hopefully, by the fourth draft I’m done and ready to send off

to my copy-editor.

P.S.: What is your current work in progress?

Would you mind telling us a little about it?

M.W.K.: The second book in the series is a blend of magical realism and hard science fiction. Elle: The Naked Singularity follows the adventures of a main character in Mauna Kea Rising in an adaptation of The Wizard of Oz. Twenty-year-old Elle Akamu slips from 21st century Earth through spacetime into a parallel universe where she suffers cultural shock in the 1970s British Hawaiian Islands. Lost in the multiverse, she finds life is about confronting her past, finding love, and accepting a new home. A stranger in a strange land, this next book wrestles with our oldest questions—what is the nature of the universe? Are there hidden dimensions around us? What does it mean to be human?

P.S.: Can you give us any hints about what

readers can expect as your Multiverse series continues?

M.W.K.: Sure. In keeping with the non-linear concept of time, you can read the other books in any order. I know that sounds a little crazy, but you’ll just have to read them to see for yourself. You might also get new insights by rereading them last-to-first after they all come out. Elle explores aspects of the multiverse and why time travel doesn’t necessarily violate the Grandfather Paradox. The third book, Yesterday’s Destiny, speculates on the point of deviation from our own universe that created the world in the Lost in the Multiverse series.

Poseidon’s Scribe: What advice can you offer aspiring

writers?

M.W. Kelly: Write and keep writing every day. Don’t read every how-to book on writing—it’ll make your head spin with all the contradictory advice out there. Join a writing group or critique circle. Your writing will improve just by reviewing material other than your own. And that brings me to another activity—reading. Read good material outside of your own genre. You’ll develop a unique voice and story ideas will spring organically if you explore literary styles beyond your own category. A great place to start is Reading Like a Writer by Francine Prose.

Thank you,

Mark.

Interested readers can find out more about M.W. Kelly at his website, his Facebook author page, on Twitter, Amazon, and Goodreads.

Poseidon’s Scribe