If you’ve just finished writing a short story and would like to get it published, the array of available markets can be confusing. I’ve blogged before about some websites with valuable information about markets and also about how you can prioritize a list of markets for your story. Today, I thought I’d delve into how the markets are divided up according to rates of pay.

The short story market is chaotic. Although there are several long-lived publication markets, there are many that are born each year, and many others (particularly during downturns in readership) that die off.

At any given time, though, there is a spectrum of markets running from those who charge readers a great deal, pay authors well, and publish high quality fiction; all the way to those who charge readers nothing, pay writers nothing, and publish fiction of variable quality. It’s that spectrum that the rating system is trying to map.

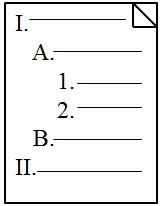

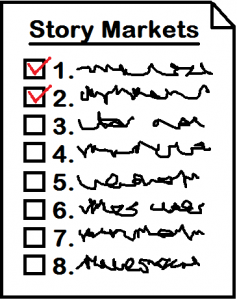

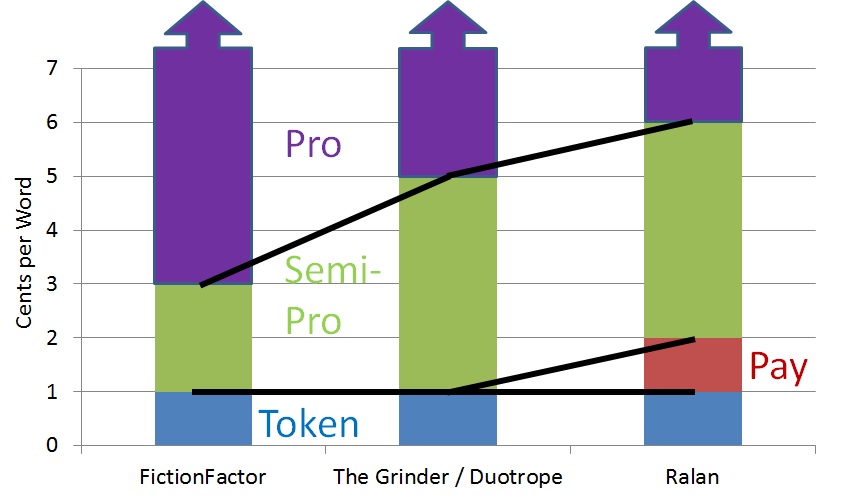

Just to make things confusing, there are various rating systems. Most have Pro (or Professional) at the top, followed by Semi-Pro, then Token, then Non-Paying (or For-the-Love).

As you can see from my chart, FictionFactor sets their Pro category at 3 cents per word and their Semi-Pro starting at 1 cent per word. However, their term for markets paying between 0 and 1 cent per word is Low. They use the term Token for markets paying a flat rate between $5 and $15 per story.

As you can see from my chart, FictionFactor sets their Pro category at 3 cents per word and their Semi-Pro starting at 1 cent per word. However, their term for markets paying between 0 and 1 cent per word is Low. They use the term Token for markets paying a flat rate between $5 and $15 per story.

Both The Grinder and Duotrope set their Pro category starting at 5¢/word.

Ralan uses 6¢/word as the lower bound of Pro markets. Ralan also includes a Pay category between Semi-Pro and Token.

Confused? I don’t blame you. You might be asking why such ratings matter, either to a writer or to any of the markets. One reason is that some professional societies, like Science Fiction Writers of America and the Horror Writers Association use market ratings to determine some membership categories. That is, you need to have published some number of stories in Pro markets to qualify for certain membership types.

Romance Writers of America categorizes some of their membership groupings by the amount of advances or royalties from a single work, not by the market rating.

A more important reason why you might care about these market rating systems is that they serve as a gauge for you to rate your own development and advancement as a writer.

Think of Non-Paying, Token, and Semi-Pro as being analogous to the minor league in baseball. Many players in that league would like to get to the majors, though some might be content where they are. The fans don’t see quite the same level of play as they would in a major league stadium, but they don’t pay as much either. Also, the fans get a chance to see players at an early stage who may very well make it to the major leagues.

Unlike the baseball analogy, though, I advocate first aiming for the top with every story. Keep sending to Pro markets until you get sick of the rejections. Only then aim at the Semi-Pros, and on down the list. Whether you get to Token or Non-Paying markets depends on how badly you want that particular story to be published. You might decide to shelve it rather than accept a lower payment.

There are some who contend that any markets not paying Pro rates (especially Non-Paying markets) are “ripping off” writers. I disagree. It’s good to have a spectrum of markets available, especially for beginning writers who want to get in print and are satisfied with a lower rate of payment while they hone their craft.

Once again, there’s another aspect of the world’s confusion and chaos cleared up for you by—

Poseidon’s Scribe