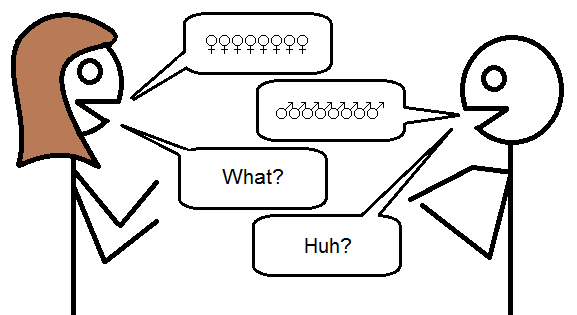

When we talk, we don’t often come right out and say what we feel. That should be the same with your fictional characters. There should be meaning below the words. That’s known as subtext.

I’ll come right out and admit this: I’m still learning how to employ subtext in my characters’ dialogue. As a trained engineer, I tend to speak plainly and strive for exactitude in meaning so I can be clearly understood. Unfortunately, many of my characters sound like me. Not good, but I’m getting better.

Let’s learn about subtext in dialogue together, then, shall we? There are some wonderful blogposts you can read, including this one on the Industrial Scripts website and this one by author K.M. Weiland.

These two sites give us techniques to practice, including having characters say:

- what they mean, but in a different way,

- something unexpected,

- something understated or ironic,

- something with actions instead of words,

- the same words or phrases again later to gain additional meaning, and

- the bare truth in a moment of high emotion.

Each blogpost also provides excellent examples from movies so you can analyze how scriptwriters accomplish the intended purpose.

The technique you choose should be consistent with your character’s motivation and personality.

Every major character has a motivation. The character wants something, or wants to avoid something. Let’s say female Character A is speaking to male Character B. A knows B can help her get what she wants, can interfere with her getting what she wants, or is neutral. Her motivation can guide you in infusing her dialogue with subtext.

Your characters also have distinct personalities. Those personality types influence both what the character says and the subtext beneath that. Therefore, both the dialogue itself, and the subtext beneath will help the reader become familiar with the character as the story proceeds.

In this blogpost, screenwriter Charles Harris discusses steps you can use to improve your use of subtext in dialogue. When you read his post, you’ll learn the details of how to:

- Practice writing subtext to hone your skill.

- Write straight text first, then alter it to suit the characters and the situation.

- Study real-life dialogue; try to detect subtext in what real people say.

- Study dialogue in fiction.

- Complete a simple exercise to develop your technique.

- Get better acquainted with your characters. Give each one a distinctive speech pattern, favorite phrase, or habitual saying. Hear their voice in your head.

- Use idle moments to imagine (and write down) ideas for subtext-filled dialogue.

- Eliminate excess words. Keep dialogue to bare bones.

- Know when to have a character spill out actual thoughts when in an extreme emotional state.

Now you know. When I say I’m Poseidon’s Scribe, I mean I’m either much more than, or not really—

Poseidon’s Scribe

This blog post comes with a giant disclaimer. I’ll be discussing general tendencies, not rules. Rather than concentrating on having a female character “talk like a woman,” focus instead on having her talk consistently with her personality, age, nationality, time period, upbringing, geographical location, and gender. In other words, the way your characters talk depends on a lot more than gender.

This blog post comes with a giant disclaimer. I’ll be discussing general tendencies, not rules. Rather than concentrating on having a female character “talk like a woman,” focus instead on having her talk consistently with her personality, age, nationality, time period, upbringing, geographical location, and gender. In other words, the way your characters talk depends on a lot more than gender.

experience is based solely on twenty years of being in small, amateur, face-to-face critique groups; not writing workshops, classes, or online critique groups; so the following advice is tuned to that sort of critique.

experience is based solely on twenty years of being in small, amateur, face-to-face critique groups; not writing workshops, classes, or online critique groups; so the following advice is tuned to that sort of critique.