You’re invited to join me at a virtual science fiction and fantasy convention this weekend. Give me a second while I find out what they’re charging for admission to this thing…wait…ah, here. No, that can’t be right. It’s free?

I guess so. You can listen all weekend to my inciteful and inspiring ideas for nuttin’. Nada. Zero dollars and zero zero cents. (Well, you’re invited to make a donation.) Here’s the Chessiecon website where you can register to attend.

Anyway, I’ve listed my schedule below, which is subject to change. All times are Eastern time zone.

| Date/Time | Title | Description |

| Fri 4:30 PM | How to be a panelist / moderator / presenter at SF/F cons | New to trying to herd cats? Not only does a moderator need to encourage panelists, stop one panelist from taking over the whole shebang, but also a moderator needs to be able to read the audience. |

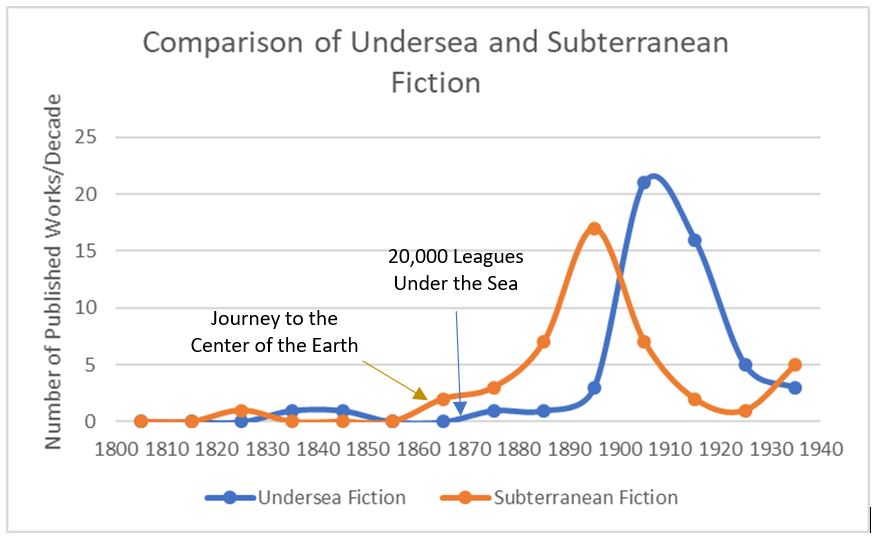

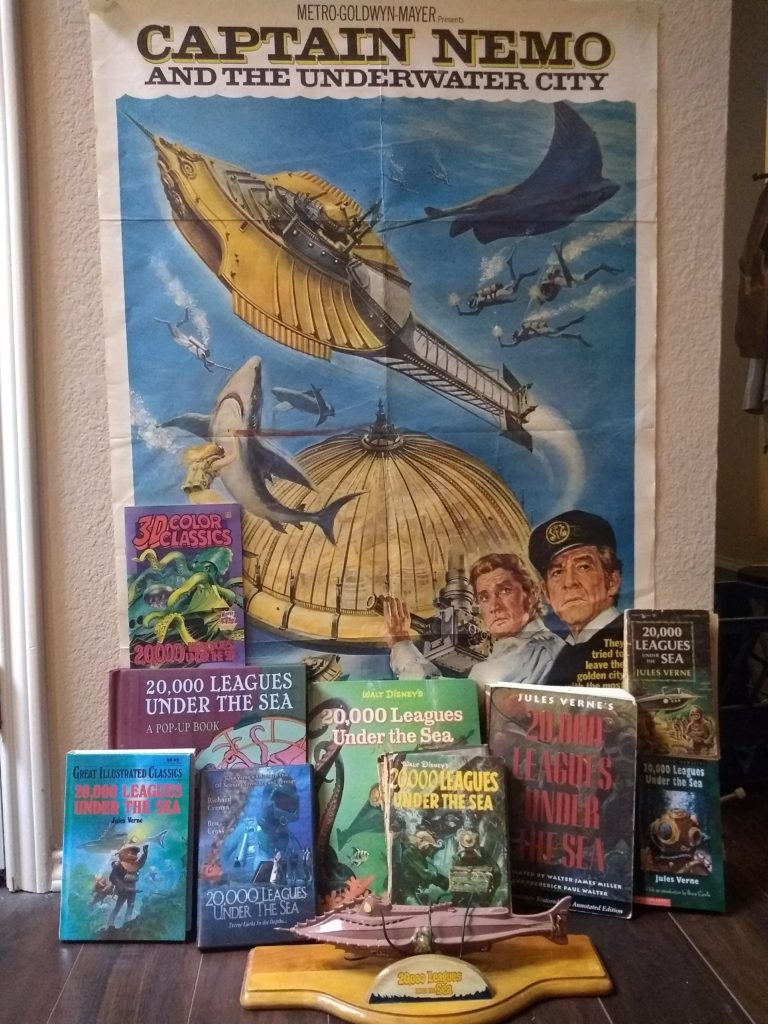

| Fri 9:00 PM | Underwater Cities. Is there merit to this idea? | What are the Engineering, Social, and Environmental limitations to expanding the areas of earth’s surface that people can inhabit? |

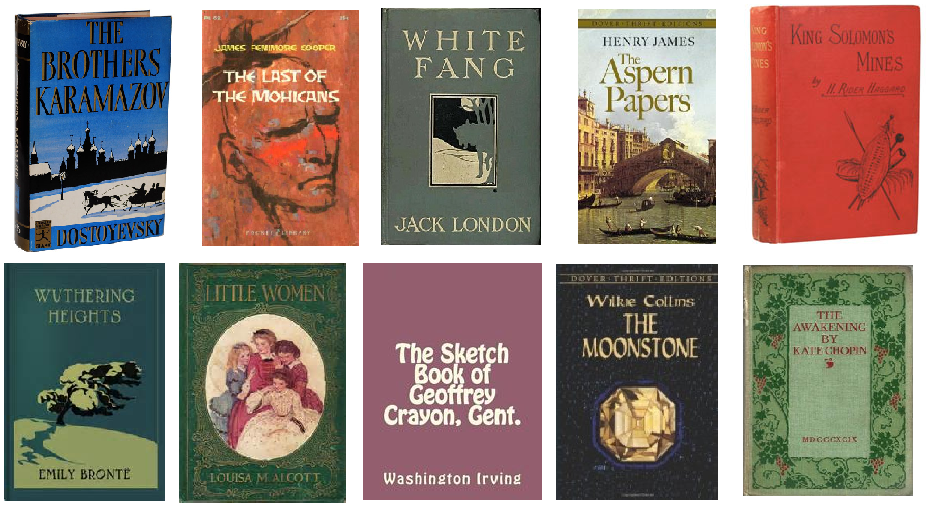

| Sat 10:00 AM | Why Read the Classics? | Do they still have something to teach us, or are they just not something of interest to a 21st-Century audience? |

| Sat 2:30 PM | Why Aren’t They Writing Like They Used To? | We all know the trope that s/ff has always has at least overtones of politics; but what other things have changed or not changed in the field? |

| Sat 4:00 PM | Pandemics Throughout History, and Their Effects on Literature | 2019-2021 is not the first regional, continental or even global pandemic in history. How have these events affected literature, be it fantasy, speculative or science-fiction literature? |

| Sat 8:30 PM | Worldbuilding in Your Story | Physical characteristics, societies, geography, languages, and what else might fit. And how this affects your stories |

| Sat 10:30 PM | What Did I Do to Survive the Great Pandemic? | How our panelists muddled through, and yet, still somehow are not zombies. Note: may be slightly delayed if the chorus runs over slightly. |

I’ll be moderating the Underwater Cities panel, the Classics panel, and the Worldbuilding panel. I’ll be a panelist for the rest.

Here’s that website one more time: www.chessiecon.org.

How many opportunities do you get to listen to me for free? Heck, I don’t even get that deal. I charge myself admission, and I pay up, ‘cause I’m worth it.

But you don’t have to pay a cent to listen to seven sensational sessions this Friday and Saturday when you’ll hear the portentous pontifications of—

Poseidon’s Scribe