Readers can be drawn to characters with mental troubles. All fictional characters have troubles, of course, since conflict is necessary to good fiction. But today I’m focusing only on characters with mental disorders.

Note: nothing in this post is meant to diminish or glorify the real problem of mental illness. People with such disorders should seek and obtain professional help, and there should be no stigma attached to that.

My purpose is to discuss how an author should portray a fictional character with a mental disorder. Anyone who reads books or watches movies knows that audiences are fascinated by such characters. Troubled characters ratchet up the conflict and drive the plot. They also give readers and viewers a glimpse into the complexities, wonders, and horrors of the human mind.

This week I attended a Zoom lecture by Loriann Oberlin, who writes fiction under the pen-name Lauren Monroe. Unlike me, she is an expert in psychology. Her talk inspired this blogpost, but everything in this post is my interpretation.

In her talk, Ms. Oberlin referenced the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). This book, published by the American Psychiatric Association, discusses disorders such as neurodevelopmental; schizophrenia spectrum; bipolar; depressive; anxiety; obsessive-compulsive; trauma- and stressor-related; dissociative disorders; somatic symptom; feeding and eating; elimination, sleep–wake; disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct; substance-related and addictive; neurocognitive; personality; and paraphilic; as well as conditions such as sexual dysfunctions and gender dysphoria.

Ms. Oberlin stressed the importance of doing your research so you can depict a particular mental disorder correctly. I’d amend that advice just a bit. It’s easy, when conducting research, to go down rabbit holes and research too much. So, learn when to quit doing research and shift to writing your story. If your character’s behavior and speech don’t exactly match some known disorder, don’t worry about it too much. The APA occasionally comes up with new ones.

Here are my suggestions if you wish to create a troubled character:

- You should include a backstory explaining the character’s behavior. You needn’t start the story that way, but perhaps work it in as a flashback. Did the disorder spring from one or more events in the character’s childhood?

- You need to reveal the character’s symptoms to the reader early and throughout. Remember to show, don’t tell, these symptoms.

- Is the troubled character the protagonist? If so, then some sort of change is required in the story. Perhaps the character takes steps to overcome problems caused by the disorder. Or maybe the disorder brings consequences for which the character must suffer. Perhaps the character struggles with the disorder, then finally comes to terms with it.

- If a different character is the protagonist, then the troubled character need not change, but your protagonist must change, perhaps by learning to accommodate the troubled character’s disorder.

Here are examples where I’ve used troubled characters in my fiction:

- In “Ripper’s Ring,” Horace Grott is a loser, barely qualified for his job carting bodies to the morgue in London in 1888. He comes upon the legendary Ring of Gyges that enables its wearer to turn invisible. In time, that new-found ability turns Horace into a serial murderer—Jack the Ripper. The story is partly in Horace’s point of view, and partly in that of the detective tracking him down.

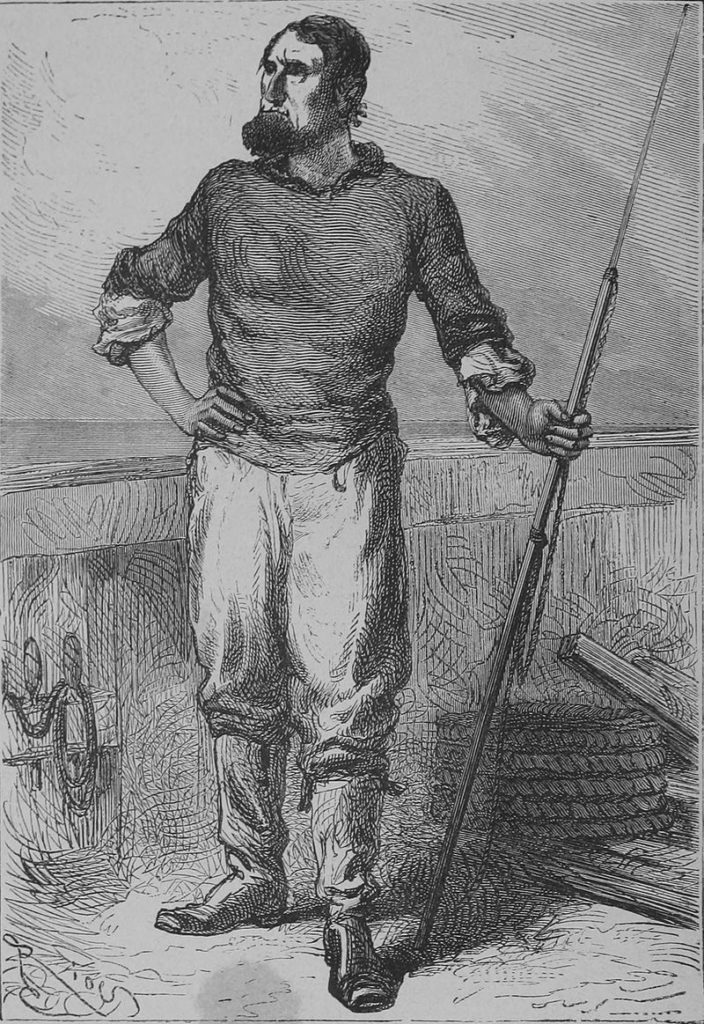

- In “The Six Hundred Dollar Man,” Sonny Houston is a nice young man with virtually no negative traits, living in the Old West. After being trampled by farm animals, he’s given a steam-powered arm and legs by an inventive doctor. These superhuman abilities change Sonny and he descends into madness. The story is told from the point of view of the doctor, who comes to realize the consequences of his well-meant invention.

- In “A Tale More True,” no character has a mental disorder, but I cite the story because Ms. Oberlin mentioned how ‘Munchausen Syndrome’ has been renamed ‘factitious disorder imposed on another.’ The famous fictional character Baron Munchausen, the one with such fanciful lies, appears in my story. The attention given to the baron’s tall tales inspires my protagonist, Count Federmann, to make his own trip to the moon.

Now that you’ve read this post, if you do write a story about a character with a mental illness and that story becomes a bestseller, and you’re invited to make speeches and give interviews, don’t forget to thank—

Poseidon’s Scribe