Writers should be versed in the classics of literature to some extent, and I had never read The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Victor Hugo, published in 1831. So I read it. I just completed listening to all 19 CDs of the Recorded Books version narrated by the incomparable George Guidall.

It would be easy to do a straight review and give this monumental novel a rating of 5 seahorses. Hunchback well deserves my highest rating for its universal themes and timeless characters.

It would be easy to do a straight review and give this monumental novel a rating of 5 seahorses. Hunchback well deserves my highest rating for its universal themes and timeless characters.

However, you can find those sorts of reviews anywhere in print and online. I propose to do something different here. Since the purpose of my blog entries is to tell you things I wish someone had told me when I was beginning to write fiction, I’ll do a different sort of review. I’ll analyze the book as if it had been written today for English-speaking readers. If an author tried to market this book today, what would editors say? I know this is very unfair to Victor Hugo, and I apologize, but I believe this sort of review might be more useful to you, a prospective writer.

So here goes, and I’ll start with a few positives. Hugo has crafted a work with well-drawn, tragic characters, and then proceeded to put each of them through hell. Quasimodo is a deaf and grotesque cripple who (1) feels an understandable but undeserved loyalty to the Archdeacon who saved him, (2) loves a woman who could never love him back, and (3) is forced to defend a church alone against an irate mob. Esmeralda is a beautiful young girl raised by gypsies who searches for her parents and loves a soldier who does not return her love; moreover, she is accused of witchcraft and is both tortured and condemned to die. Archdeacon Claude Frollo is tormented by his love for Esmeralda to the point of insanity. In addition to these vivid characters, Hugo’s language–his style and use of metaphors and similes–survives even the translation from French to English.

So here goes, and I’ll start with a few positives. Hugo has crafted a work with well-drawn, tragic characters, and then proceeded to put each of them through hell. Quasimodo is a deaf and grotesque cripple who (1) feels an understandable but undeserved loyalty to the Archdeacon who saved him, (2) loves a woman who could never love him back, and (3) is forced to defend a church alone against an irate mob. Esmeralda is a beautiful young girl raised by gypsies who searches for her parents and loves a soldier who does not return her love; moreover, she is accused of witchcraft and is both tortured and condemned to die. Archdeacon Claude Frollo is tormented by his love for Esmeralda to the point of insanity. In addition to these vivid characters, Hugo’s language–his style and use of metaphors and similes–survives even the translation from French to English.

On the other hand (and again I’m reviewing the book as if it were a submitted work in English today), the novel has an unsatisfying hook. It gets off to a slow start and it’s not clear near the beginning what the central conflict of the story is. Moreover, the pace is slow throughout; much of the text could be tightened up. The long section on architecture, where Hugo compares books to buildings, could be either eliminated or cut way back. In general his descriptions of things are two long. There is no need for the narrator to periodically address the reader (“With the reader’s consent,…” “Let the reader picture to himself…” “Our readers have been able to observe…”).

If Mr. Hugo would hope to get this manuscript published today, he would have considerable editing left to do. As it stands, I would have to give it a rating of three seahorses.

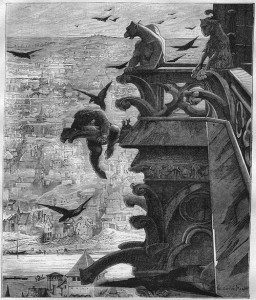

All right, quiet down out there, Victor Hugo fans. You’re asking (in loud tones) how I dare to give this colossal work of literature a mediocre rating. I believe I explained that. My aim, as always, is to help beginning writers–those who hope to get published early in the 21st Century. I reluctantly had to downgrade Hunchback, but I only did so to aid budding authors. Even so, I’ll take legitimate comments from anyone about this review. So go ahead and (figuratively) heave down your timbers and your stones, pour down your molten lead upon–

Poseidon’s Scribe