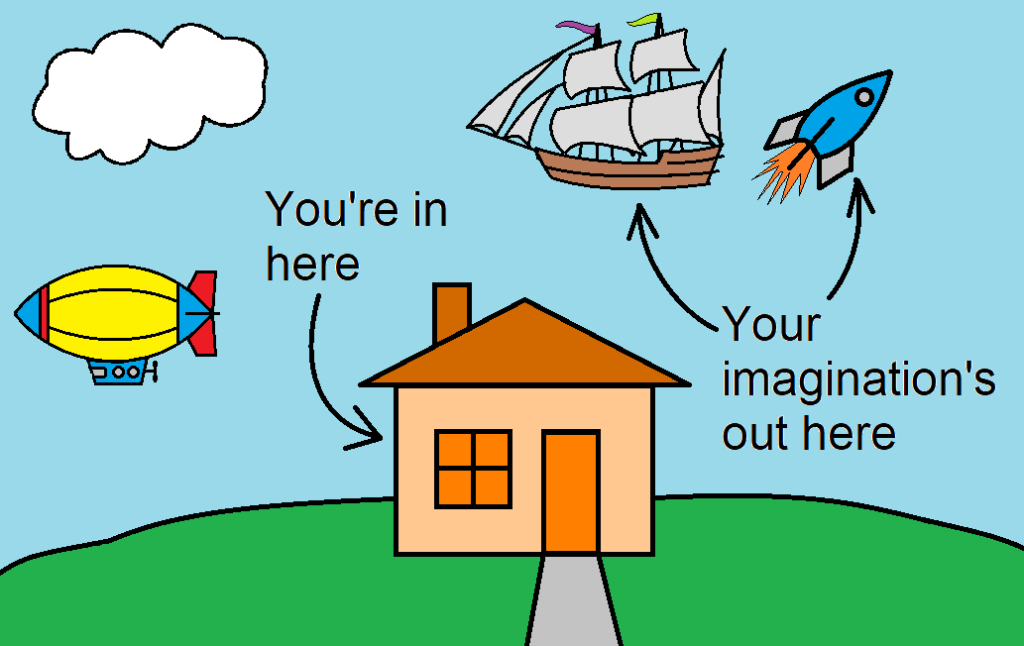

The reason you scramble out of bed each day, wide-eyed and raring to go, is simple. You’ve got things to do. More specifically, you have goals to achieve. As Snuffy Smith always said, “time’s a’wastin’!”

What’s that? You don’t bound out of bed? You (shudder) don’t have any goals?

Hoo boy. We’ve got to talk.

There is enormous power in the practice of committing to goals. There are also numerous side benefits for you, incidental to achieving the goal itself.

I’ll offer two examples from my life. Many years ago, my younger sister called me; she was excited because she’d decided to train for, and run, a marathon. Prior to her call, I’d given no thought to running a marathon myself. After that brief phone call, I was committed.

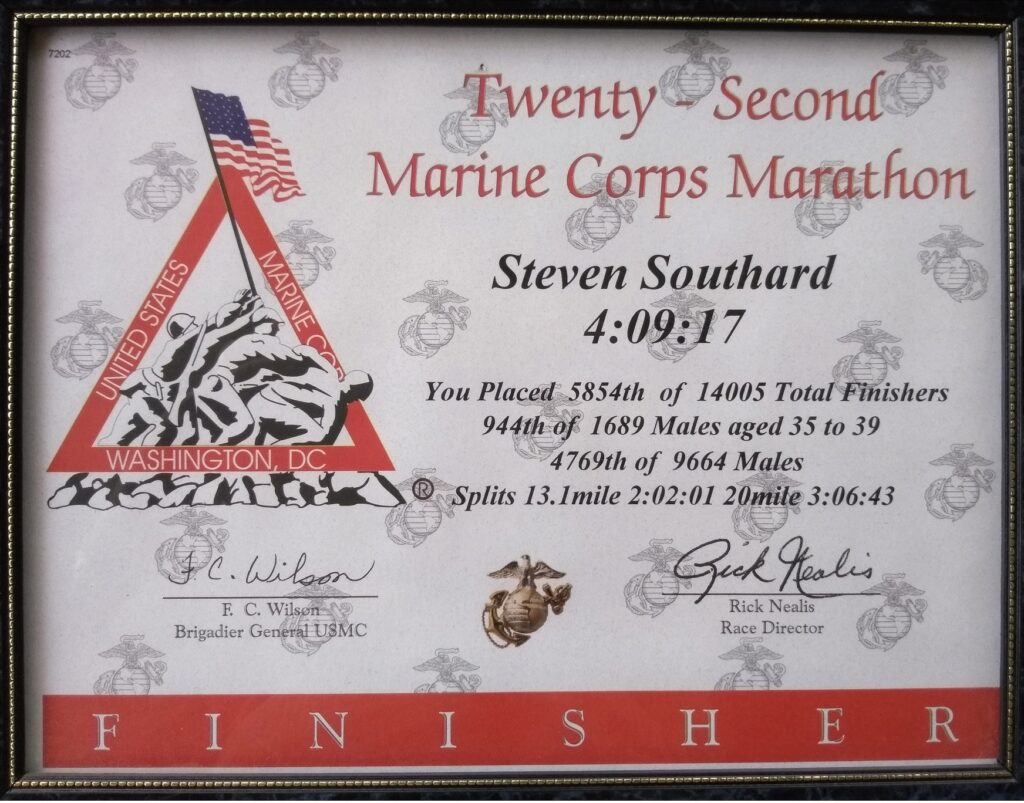

I registered for the Marine Corps Marathon in Washington D.C., at that time about nine months in the future. I bought a book about training for a marathon and followed its plan, including maintaining a running log. Often during that year, I thought I’d never be ready in time. However, I knew the Marines were unlikely to postpone their race just to accommodate me. Still, I ran and finished the race.

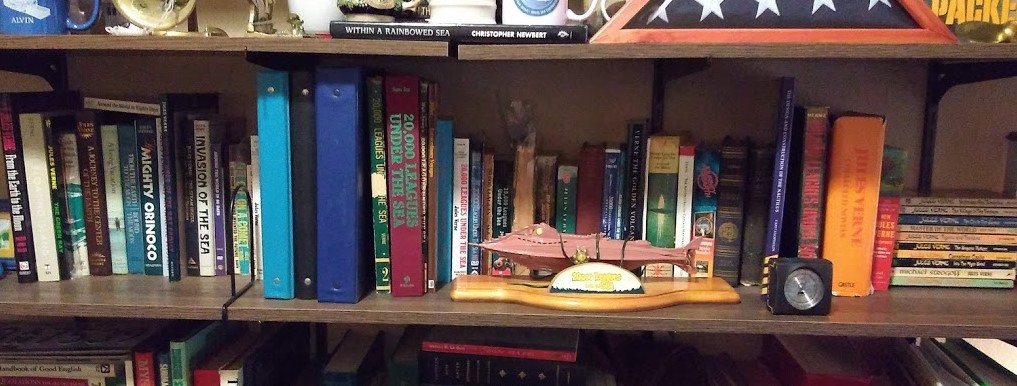

As a second example, I recognized, about a year ago, that June 20, 2020, will be the 150th anniversary of the publication of Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. I set a goal of launching, on that exact date, a sesquicentennial anthology honoring Verne’s novel. I’ve never co-edited an anthology before, but goals should push you outside your comfort zone, beyond your known limits. They should be big, audacious, and grand.

So far, progress toward that goal has been good. Things are proceeding well. We’ve received wonderful stories and look forward to publishing the anthology on time.

Enough about me. What about your goals?

According to this article by Anya Kamenetz, there are mental and physical health benefits to setting and achieving goals. A University of Toronto study showed performance in school improved for all ethnic groups and genders of students who wrote down and worked toward goals.

When you decide to set a goal, I believe it’s important to write it down, not just memorize it. Performing that simple act:

- Cements the goal and affirms your commitment to it;

- Gives direction and meaning to your actions;

- Paints a picture, a vision, of the future to which you aspire;

- Creates an urge within you that prods you to achieve daily progress and nags you when you fall behind;

- Helps you overcome setbacks, laziness, disenchantments, and obstacles;

- Provides immense satisfaction when every milestone and the final goal are met;

- Boosts confidence in your ability to achieve; and

- Spurs you on to setting a new goal after each achieved one.

What’s that you say? You have a problem with the entire ‘goal’ concept? You say you don’t set goals anymore because you feel bad about yourself when you fall short?

Well, you may not achieve all your goals. I haven’t met all the goals I’ve set either. But you shouldn’t beat yourself up over failures. Missing a goal doesn’t mean you’re a bad person.

Learn what you can from that failure and set another goal. Consider a smaller one, easier to achieve. Celebrate when you achieve it. You’ll build your confidence one win at a time.

Pretty soon you’ll be bounding out of bed each day, just like—

Poseidon’s Scribe