While editing your manuscript, you might wish to look at it from three different viewpoints, or perspectives, to give your story a complete assessment.

A nice post by Jennie Nash inspired this blogpost, but I’ve taken her ideas in a different direction. I concur with her that it’s helpful to get out of your own head and try to see your story through other eyes. That will help you decide what to cut, what to keep, and what to rephrase.

Here are the three perspectives I suggest:

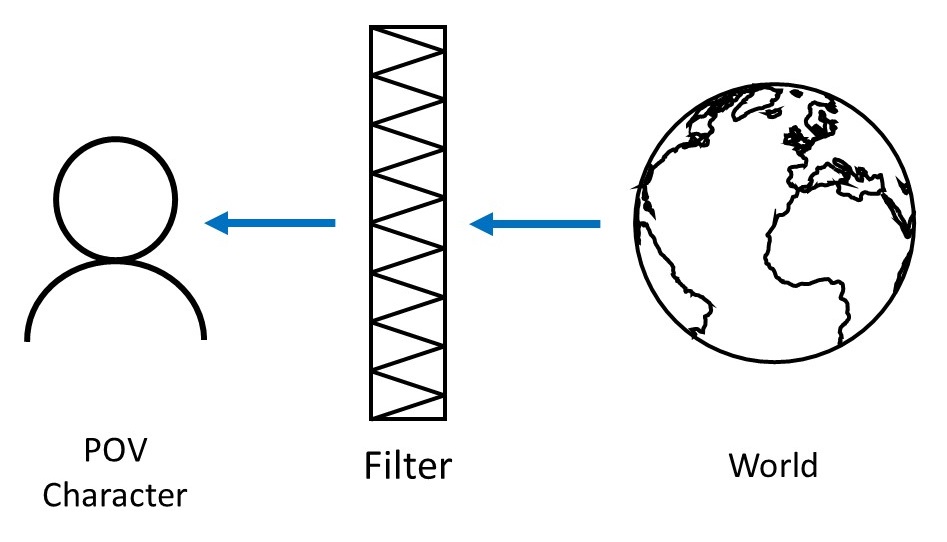

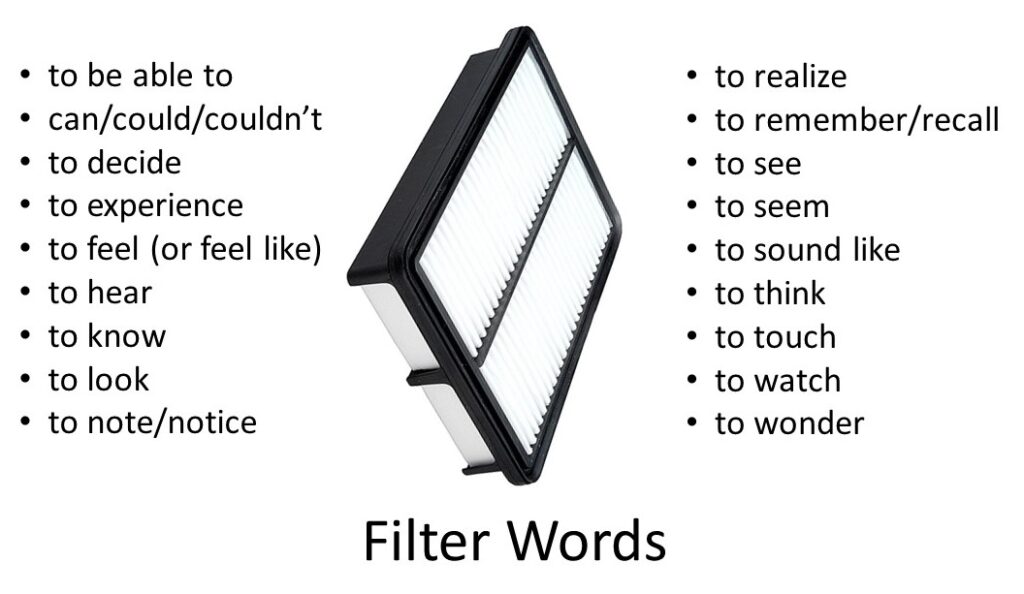

Your Characters. Take each of the major characters in your tale, get inside their heads, and think about the story from their point of view. Are there parts that don’t work? If your character is telling you, “I would never do (or say) that,” listen to that voice. It means that person is unrealistic—literally uncharacteristic. Either change the dialogue or action, or revise the character to make the voice and action plausible.

Your Readers. The audience for your story doesn’t see the story as you do. A reader has limited time, and a lot of other stories to read. The beginning of your tale really has to hook the reader, grab attention and not let go. In the middle of your story, you can’t afford many boring parts, or any parts that are both boring and lengthy. Shorten or get rid of them before your reader throws your book away. There may well be passages you love, but are unnecessary when viewed from a reader’s point of view. Delete them.

Your Editors. Don’t forget those nice folks with the eyeshades and blue pencils, the ones who decide whether to risk the publisher’s money and reputation on your story. They really don’t see your story as you do. They see every grammar and spelling mistake, every plot hole, every cliché and stereotyped character, every ambiguous phrase, every confusing description, and every character that acts out-of-character. It’s best if you see these things first and not give the editor an excuse to reject your story.

There. When you’re done, you will have viewed your story from three perspectives, much as a blueprint depicts an object using front, top, and side views so a manufacturer can understand it from multiple dimensions.

Of course, there’s a sort of fourth dimension involved here, and that’s—

You. You had the idea for the story in the first place and you wrote every word of it. What’s more, it was really you pretending to be characters, readers, and editors throughout the editing process above. It’s been all you every step of the way. When the story is published, it will have your name on it. Are you proud of it? If not, perhaps you ought to let that story sit and percolate awhile before picking it up again for further editing.

I’ll conclude with one interesting trick of perspective, one little-known fact about a peculiar optical illusion. When viewed from any angle, I’m still—

Poseidon’s Scribe