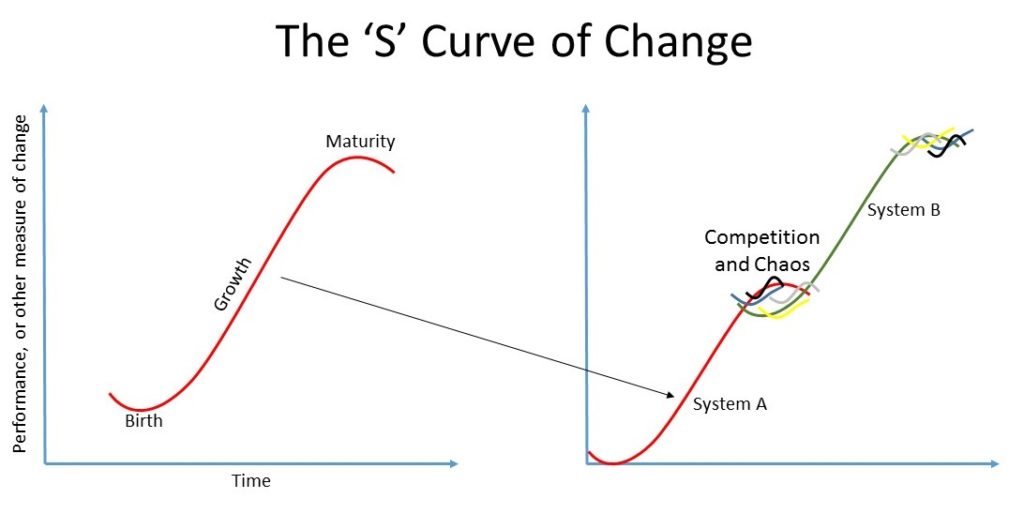

Change is all around us. It’s amazing to watch, and it tends to follow a single, characteristic pattern. Even though the pattern repeats, it often surprises us.

That pattern goes by various names, including the Change Curve, the ‘S’ Curve, the Sigmoid Curve, and the Logistic Curve. I’ll call it the ‘S’ Curve, mainly because my name is Steve Southard, and I’m fond of that letter.

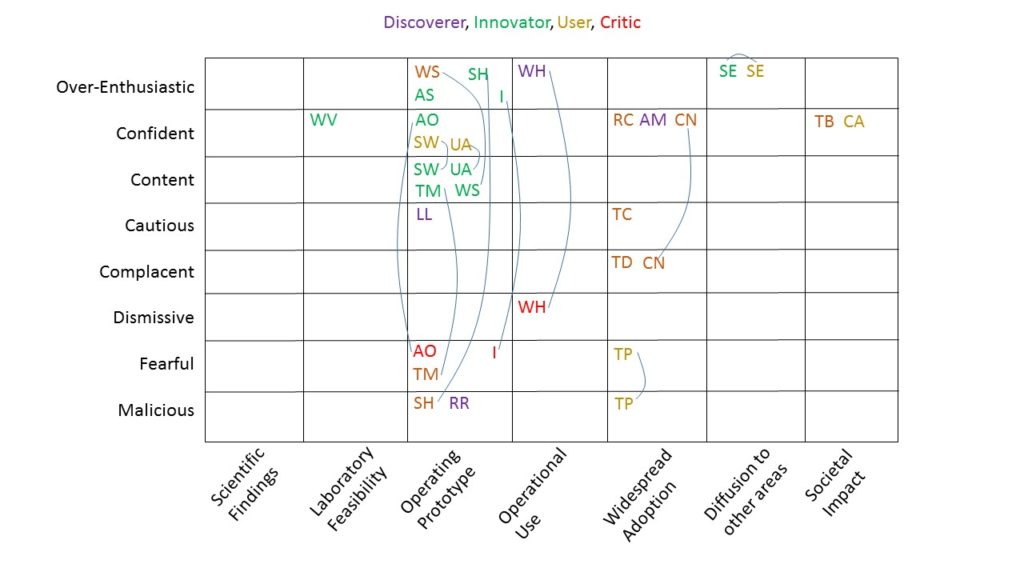

Consider a thing, or entity. As we’ll see, it can be almost anything. It begins in a period of uncertainty, and may not show much potential at first. Then it establishes itself, finds a comfortable and promising track, and pursues that. It enjoys a period of sustained and impressive growth, making minor tweaks, but generally continuing on its established path. Finally, it reaches some limit, some constraint it had not previously encountered. That constraint proves its undoing, and it enters a period of maturity, decline, and termination.

During that maturity portion, other things/entities/systems compete for supremacy. This is a period of uncertainty and chaos. It’s unknown which competitor will survive, but eventually a single winner emerges and becomes the successor, which experiences its own period of sustained growth, and its own eventual maturity.

As you read my description of the curve in the previous two paragraphs, I’m guessing you thought of at least one example of this. The ‘S’ curve resonated with you in some way and you knew it was true.

A quick search on the Internet showed examples related to language, to socio-technological change, to human height, to animal populations, to career choices and motivation, to stock prices, to business, and to project management. There were also discussions of the curve as a general model of change here, here, and here.

The ‘S’ Curve is everywhere!

Sometimes we can perceive this curve in an erroneous way. If its time-span is long enough, say, a significant fraction of a human lifetime, people observing the entity during its growth phase often assume that phase will continue forever. Why not? It’s been that way a long time. Why shouldn’t it continue upward like an exponential curve? However, few things do.

Consider automobile engines. At the beginning of the 1900s, it wasn’t clear which type of engine (steam, electric battery, or gasoline) was superior. The internal combustion gasoline engine won and became the standard for many decades. An observer in the 1960s could well assume cars would have gasoline engines forever. Now pollution has become a problem and that engine has reached its efficiency limits, so other technologies are beginning to compete.

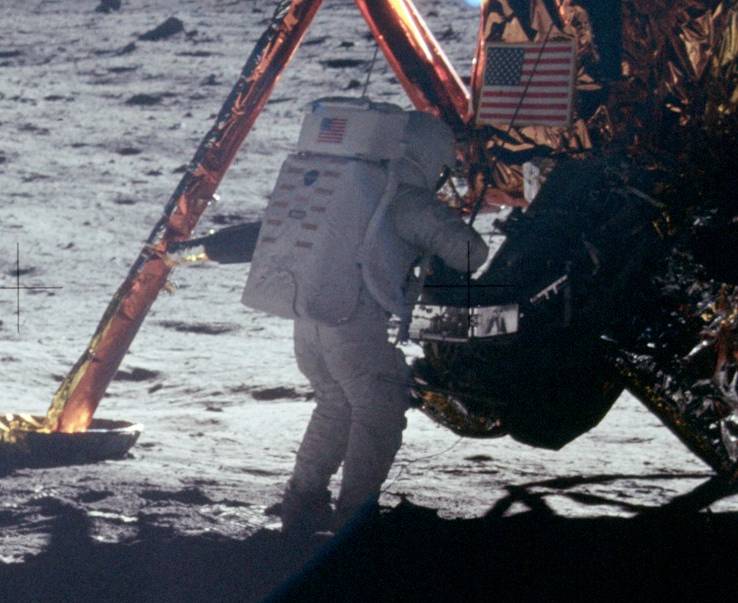

Consider manned space exploration, as I did in last week’s blog post. During the Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo programs, NASA made steady progress. Observers in the late 1960s could have concluded there would be many follow-on programs in the 1980s, 1990s, and later, taking astronauts to Mars, the asteroids, the outer planets, and eventually, the stars. Instead, manned space exploration encountered constraints such as cost and waning public enthusiasm, so it has remained stalled to this day.

The technologies in my fictional stories all follow that ‘S’ Curve model. Usually my tales take place during the periods of disruption and chaos.

In fact, the story-writing process itself follows the ‘S’ Curve, with little progress during the idea creation stage, then rapid progress as I churn out the first draft, then a slow period of final editing and subsequent drafts before I consider it finished and suitable for submission.

As you experience change in your life, don’t assume things will remain the same. Know that all things reach their limits and end. When things seem chaotic, seek out the winning successor. Despite all this change, you can always count on—

Poseidon’s Scribe