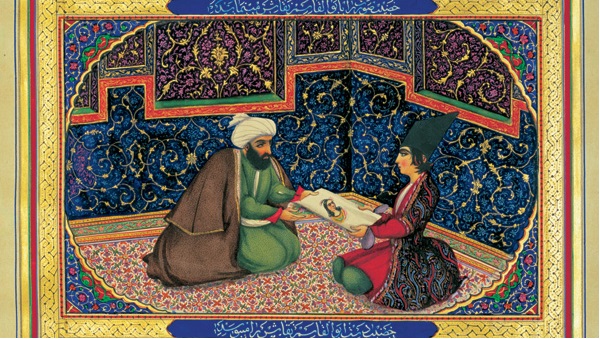

Welcome, budding writer, into the sultan’s palace in 9th Century Persia. The sultan’s former wife was unfaithful, and he now distrusts all women. For the last 1,001 nights, he’s taken a woman to bed and ordered her execution the next morning, to ensure she couldn’t cheat on him.

Now, Scheherazade, it’s your turn.

Luckily, you know a story that might keep the sultan interested. You also know when to interrupt your story so the sultan will be forced to delay your execution so he can hear the ending the next night.

Luckily, you know a story that might keep the sultan interested. You also know when to interrupt your story so the sultan will be forced to delay your execution so he can hear the ending the next night.

During the next night, you’ll finish that story and start telling a new one. Again, you’ll pause at the right point, leaving a cliffhanger, and the sultan will temporarily spare you again. How long can you keep that up, knowing the moment the sultan gets bored, you’re dead?

Recently, I read the book Talking About Detective Fiction, by the late P.D. James. At one point, she compares readers to the sultan in the Scheherazade tale. Like him, readers can be insatiable, hungry for a good, new story. They always want more, and each tale must be different from the previous ones, fresh and interesting.

That metaphor casts an author like you in the role of Scheherazade. You’re the one running the risk of boring the sultan and of getting (metaphorically) beheaded at dawn. If your next book fails to live up to the standards of the last one, readers will stop buying, and all that royalty money will stop rolling in.

Are you feeling the pressure yet?

Perhaps not. Maybe you’re thinking the metaphor doesn’t apply to you. Sure, it applies to a successful author with an established readership, like P.D. James. If only you came up with an engaging series character, like Scheherazade’s Sinbad or P.D. James’ Adam Dalgliesh, then readers would keep demanding more stories featuring that character.

But you’re a beginning writer. You don’t yet have flocks of devoted readers anxiously awaiting your next book. You’re no Nora Roberts, Ken Follet, David Baldacci, or Stephanie Meyer. You’re no Scheherazade. You think.

Sorry, you don’t get out of my metaphor that easily.

How, Scheherazade, did you come to this point? You’ve read voraciously and amassed a vast collection of books. You’ve memorized many stories. You’ve come to understand the structure of a tale, how writers accomplish their craft. You’ve practiced your storytelling techniques and have honed your skill in hooking listeners with your words and keeping them spellbound.

How, Scheherazade, did you come to this point? You’ve read voraciously and amassed a vast collection of books. You’ve memorized many stories. You’ve come to understand the structure of a tale, how writers accomplish their craft. You’ve practiced your storytelling techniques and have honed your skill in hooking listeners with your words and keeping them spellbound.

You’ve prepared for this moment. Indeed, you volunteered for it.

See? The metaphor’s still apt. If you’re not yet Scheherazade, the accomplished story-weaver who sits before a sultan, then you’re a younger Scheherazade training yourself and learning the writing craft.

You learn it because you want to; you crave it. You love stories; an inner impulse drives you to understand more deeply how they work.

Now you see Scheherazade did indeed feel pressure to tell new and interesting tales, but that pressure came from within her, not from the sultan’s threat of execution.

It’s all about the stories. May you have 1,001 tales to tell and may they fascinate your sultan. After all, budding writer, you’re Scheherazade. And so is—

Poseidon’s Scribe