In a previous blog post, I explored how Benjamin Franklin, an early champion of self-help, might advise us on how to improve our writing. To recall, Ben identified weaknesses in his own character and flipped around those negative weaknesses into their corresponding, positive virtues, toward which he strived.

In that earlier post, I made a list of fifteen fiction-writing virtues, encouraged you to make a similar list, and then left you on your own. Today, I’m picking up where I left you stranded, and providing a structured approach for applying those virtues as you write.

Ben Franklin took his list of thirteen virtues and focused on applying one per week. He kept a log of his success rate, noting when he succeeded and failed. That simple and easy method might not work for the fiction writing virtues, since the one you’ve selected might not apply to what you’re doing that week. Your virtue list, if it’s anything like mine, might be more event-based.

Ben Franklin took his list of thirteen virtues and focused on applying one per week. He kept a log of his success rate, noting when he succeeded and failed. That simple and easy method might not work for the fiction writing virtues, since the one you’ve selected might not apply to what you’re doing that week. Your virtue list, if it’s anything like mine, might be more event-based.

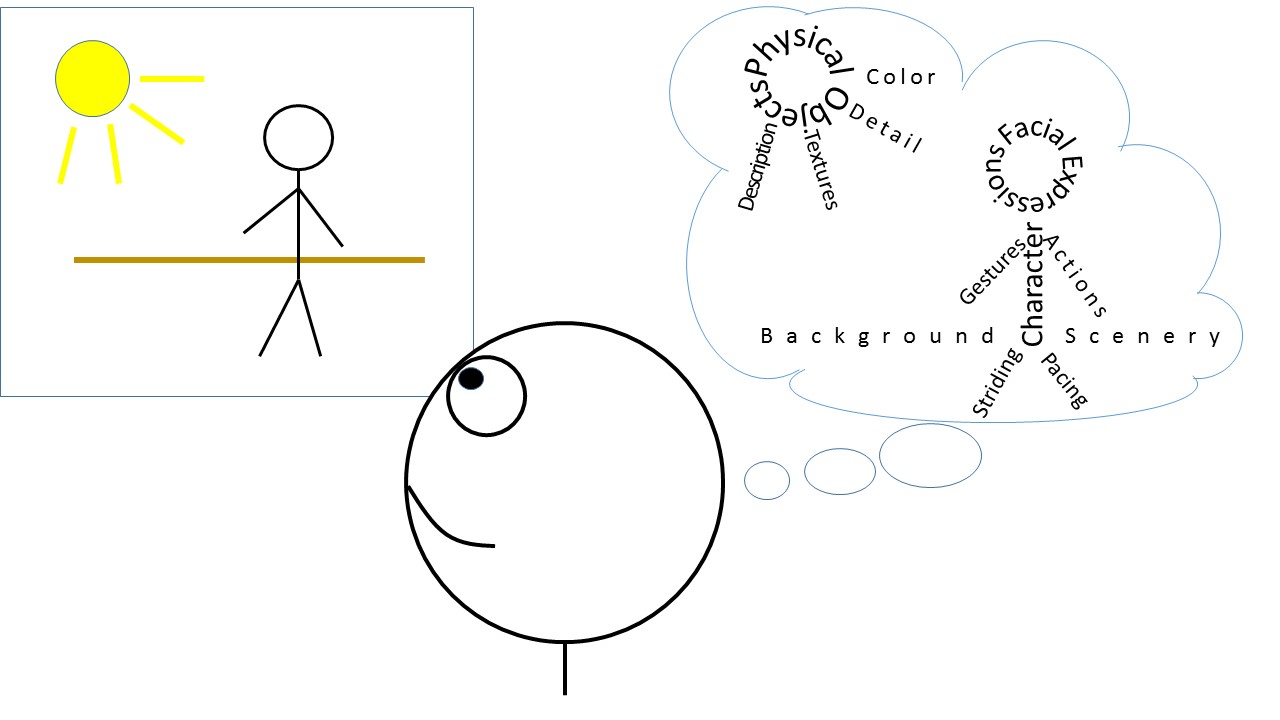

What you need is a mechanism for (1) remembering, (2) applying, (3) recording, and (4) reassessing your virtues:

- Remembering means that the applicable event-based virtue will appear before you when that given event starts, so it’s a reminder to exercise that virtue.

- Applying means that, in the moment of decision, you choose to act upon your virtue and do the virtuous thing.

- Recording means that you’ll keep some sort of log or journal of your success and failure.

- Reassessing means that once one or more of the initial virtues have become an ingrained habit, you strike it from the list, consider other weaknesses in your writing that require improvement, and add new virtues to work on.

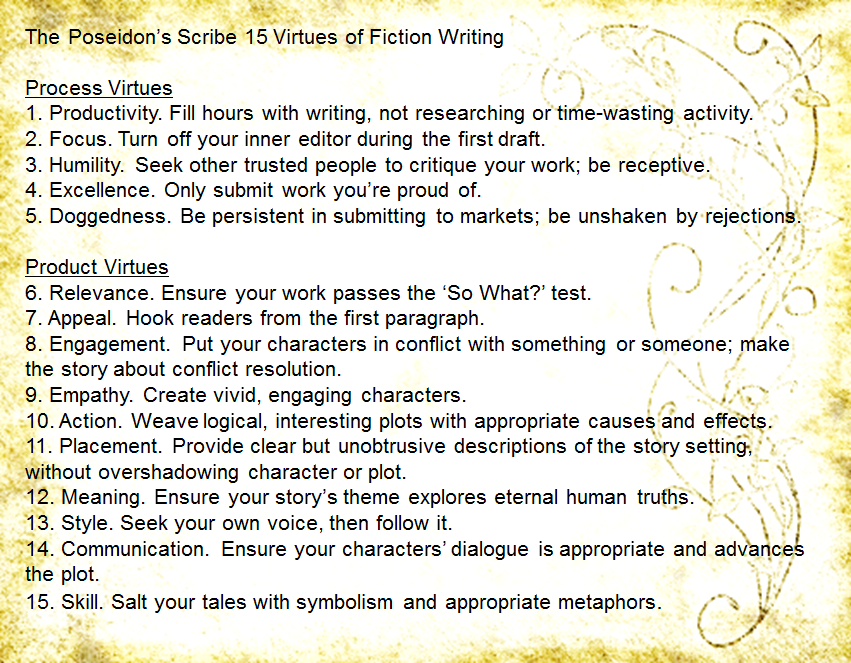

From my earlier blog post, here again are the 15 fiction-writing virtues I came up with. Reminder—yours will likely be different.

I had split the virtues into five Process virtues and ten Product virtues. Here are a couple of tables showing to which parts of the story-writing procedure each process virtue applies, and to which story elements each product virtue applies.

| First draft | Self-Edit | Critique | Submit | Rejections | ||

| Process Virtues | 1. Productivity | X | X | X | X | X |

| 2. Focus | X | |||||

| 3. Humility | X | |||||

| 4. Excellence | X | |||||

| 5. Doggedness | X |

| Character | Plot | Setting | Theme | Style | ||

| Product Virtues | 6. Relevance | X | X | |||

| 7. Appeal | X | X | X | |||

| 8. Engagement | X | X | ||||

| 9. Empathy | X | |||||

| 10. Action | X | |||||

| 11. Placement | X | |||||

| 12. Meaning | X | |||||

| 13. Style | X | |||||

| 14. Communication | X | X | ||||

| 15. Skill | X |

Remembering. The best solution is to print the list of virtues and keep it near your computer or tablet when writing, and refer to it often. Over time you’ll remember to refer to the “Excellence” virtue before submitting a manuscript, for example.

Applying. This is the most difficult part. In any given writing situation, you must do your best to live up to the virtue that applies to that situation. You’ll likely fail at first, then get better with time, practice, and patience.

Recording. If you keep a log, journal, or writing diary, that is a good place to grade yourself each day on how well you achieved each virtue that applied that day. You may learn more from failures than successes, in recognizing the causes for the failures. In time, you will strive harder to achieve each virtue simply because you won’t want to record another failure in your logbook.

Reassessing. Your list of virtues should be dynamic. Whenever you believe you’ve got a virtuous habit down pat, you can delete it from the list. Whenever you find another weakness in your writing, you can add the corresponding virtue to the list. Perhaps you’ll find that a virtue is poorly phrased, or is vague, or doesn’t really address the root cause of the weakness; you can re-word it to be more precise.

If you faithfully apply a technique similar to this, and you find your writing improving, and you gain the success you always desired, don’t forget to send (1) a silent thank-you to the spirit of Benjamin Franklin, and (2) a favorable and grateful comment to this blog post by—

Poseidon’s Scribe

Vilfredo Pareto

Vilfredo Pareto

I don’t write there very much anymore. Now I write first drafts while commuting on the subway.

I don’t write there very much anymore. Now I write first drafts while commuting on the subway. on the couch in the living room. In good weather, I sometimes write out on the deck.

on the couch in the living room. In good weather, I sometimes write out on the deck. Before we get to writers, let’s discuss observation in general. While acknowledging there are other epistemological theories, I’ll assume there is a single, physical world out there, and each person observes it differently. Those differences are due to observations taken from different physical locations, accuracy of senses, mood, previous experiences, and many other things.

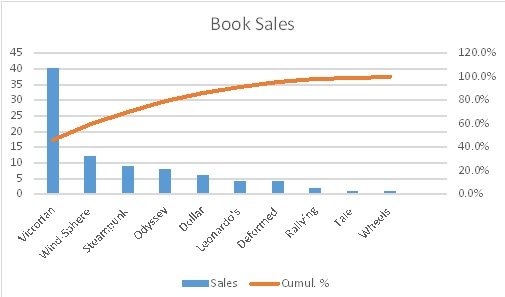

Before we get to writers, let’s discuss observation in general. While acknowledging there are other epistemological theories, I’ll assume there is a single, physical world out there, and each person observes it differently. Those differences are due to observations taken from different physical locations, accuracy of senses, mood, previous experiences, and many other things. There’s plenty of advice out there, both online and in excellent books, about marketing your stories. Many websites provide long lists with scores of tasks for you to do. It’s a bit intimidating.

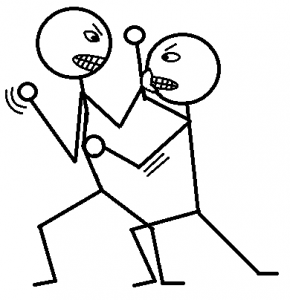

There’s plenty of advice out there, both online and in excellent books, about marketing your stories. Many websites provide long lists with scores of tasks for you to do. It’s a bit intimidating. Violent interactions can take many forms beyond individual combat. These include war, rape, terror, shooting sprees, etc. This post focuses on fights between two characters, but many of my suggestions apply to other situations.

Violent interactions can take many forms beyond individual combat. These include war, rape, terror, shooting sprees, etc. This post focuses on fights between two characters, but many of my suggestions apply to other situations.

For centuries, when much of literature served the purpose of inculcating morality, authors portrayed villains as one-dimensional characters devoted to pure evil. Writers made it easy for the reader to distinguish the villainous characters from the good ones, by appearance, speech, and actions. Authors provided no reason for the villain’s malevolent nature, nor were such reasons expected. The villain was just bad, that’s all.

For centuries, when much of literature served the purpose of inculcating morality, authors portrayed villains as one-dimensional characters devoted to pure evil. Writers made it easy for the reader to distinguish the villainous characters from the good ones, by appearance, speech, and actions. Authors provided no reason for the villain’s malevolent nature, nor were such reasons expected. The villain was just bad, that’s all.