I just finished listening to the audiobook version of Soulless by Gail Carriger put out by Recorded Books, and performed by Emily Gray. I’m not a regular reader of romance novels, but I do enjoy steampunk so I thought I’d give this one a try.

I just finished listening to the audiobook version of Soulless by Gail Carriger put out by Recorded Books, and performed by Emily Gray. I’m not a regular reader of romance novels, but I do enjoy steampunk so I thought I’d give this one a try.

The book is set in an alternate version of Victorian London in a world that has come to accept the co-existence of werewolves and vampires with humans. In fact there is a Bureau of Unnatural Registry (BUR) to keep track of all the supernatural creatures. Alexia Tarabotti is not supernatural, but is a rare breed of human born without a soul. However, this status as a “preternatural” allows her to turn any werewolf or vampire into its human form at her mere touch.

The book begins with a vampire trying to attack her, and dying in the process. How could a London vampire not know she was a preternatural? Thus the investigation begins, which requires the services of Lord Conall Maccon, head of the BUR. Soon we learn about Alexia’s overbearing mother, catty sisters, best friend Ivy Hisselpenny (she of the always outlandish hats), and flamboyantly gay vampire Lord Akeldama.

Oh, yes, and Alexia falls in love. I am not the best judge of romance novels, but I did enjoy many aspects of this book. Carriger captured the sense of the time and locale well. The characters were well-drawn and had a few complexities and interesting quirks. The love relationship was, for the most part, believable and well-paced, and I think the book’s target audience should be well able to identify with Alexia. The reading by Emily Gray was excellent; she made the characters come alive and her accent helped transport me to the novel’s world.

However, there is a long stretch of very little action between the opening scene and the final confrontation. A long epilogue follows the final actions, perhaps in order to set up the later books in the series (of which this is the first). There are frequent character point-of-view switches, but in general they are executed in a clear manner.

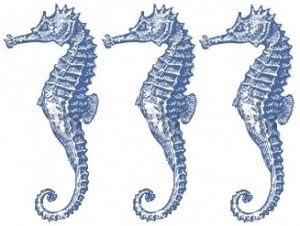

Using my book review rating system, I’m going to give this book 3 seahorses. I recommend it if you enjoy quirky romances, or supernatural fantasies. It’s teetering on the edge of what I’d call steampunk though. If you’ve read it and have a different view, please leave a comment for–

Using my book review rating system, I’m going to give this book 3 seahorses. I recommend it if you enjoy quirky romances, or supernatural fantasies. It’s teetering on the edge of what I’d call steampunk though. If you’ve read it and have a different view, please leave a comment for–

Poseidon’s Scribe