Bet you didn’t expect me to write a blog entry on writing romance short stories, did you? Well, for one thing, if you desire to become an author, you should learn to write about anything, even topics or genres you know little about or have little interest in. You never know what you’ll end up being good at.

Second, it’s hard to ignore the fact that the romance genre has a vast and insatiable readership. Perhaps not so much in the short story length as in the novel length, but again, what if you’ve got a potentially great romance writer inside you, but you never try the genre to find out?

And, it turns out I have written a couple of short story romances. “Within Victorian Mists” is a steampunk romance, and “Against All Gods” is a romance story set in Ancient Greece. So I am nominally qualified to discuss the topic.

And, it turns out I have written a couple of short story romances. “Within Victorian Mists” is a steampunk romance, and “Against All Gods” is a romance story set in Ancient Greece. So I am nominally qualified to discuss the topic.

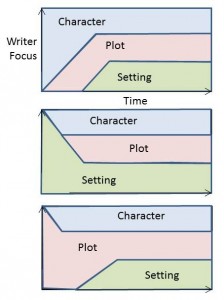

To figure out what’s special or different about romance short stories, let’s start with basics. Any fictional story must have certain elements, including character, plot, conflict, setting, style, and perhaps theme. We’ll dispense with the last three by saying that romance stories can take place in just about any setting, be written in any style, and can explore just about any theme.

Romance stories are character-driven. The characters must be intriguing and complex. The point-of-view character should have aspects with which readers can identify and empathize.

The plot is the emerging love between the characters. Choose your events such that they enable the characters’ love to either develop, or be tested, or both.

The conflict is the protagonist’s struggle to attain love itself, not the sexual act or the fleeting emotions of love, but the deep and shared realization that the two major characters cannot live without each other.

In a short story, you’re going to have to be choosy. It’s very difficult, in just 1000 to 10,000 words, to encompass the typical progression of a love story in its entirety, from the first meeting, through the burgeoning attraction, through the testing or challenge, to the final realization of love. There’s a natural pace to the process of falling in love, and the short story length doesn’t fit that pace as well as the novel length does.

Consider selecting one vignette, one emotion-charged event of a larger love story, and leave the earlier parts as backstory, and just hint at the later events. To explain what I mean, let’s consider what Christie Craig and Faye Hughes describe as the plot points of a romance story, the events that sum up to the plot arc:

- Introduction/meeting

- First acknowledgement of attraction

- First acknowledgement of emotional commitment

- Dark moment (what I’d call a test of love’s strength)

- Resolution

Your short story could consist of just one of those events, and hint at the rest. Charge your story with emotion, and ensure the protagonist experiences an internal change in the direction of love, and that could be sufficient. It might be all you can manage within a short story format.

Have you written a romance short story? Submitted it for publication? Leave a comment and let me know what happened. When you began writing did you ever think you’d write a romance? No? Neither did—

Poseidon’s Scribe