Literary scholars consider Jules Verne’s novel 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea to be a classic. Why? Let’s dive deep into that subject.

First, as a reminder, I have teamed up with the talented writer and editor Kelly A. Harmon of Pole to Pole Publishing with the intent of producing Twenty Thousand Leagues Remembered, an anthology of stories paying tribute to Verne’s submarine novel. Our antho will open for submissions soon, as detailed here, and will launch on June 20, 2020, the sesquicentennial of 20,000 Leagues.

What makes a classic book, and why include 20,000 Leagues in that category? I like the definition put forward by Esther Lombardi in this post. She says a classic: (1) expresses artistic quality, (2) stands the test of time, (3) has universal appeal, (4) makes connections, and (5) is relevant to multiple generations.

Let’s find out if Verne’s work meets these standards.

Artistic Quality

This attribute concerns whether the book was well written by the standards of its time and whether it expresses life, truth, and beauty with artistic excellence. Although much of Verne’s prose seems stilted today, and the book’s over-long descriptions of the submarine and various fish tend to bore today’s readers, the artistic merit of the work certainly met the literary standards of its era. No mere adventure novel, it explored deep themes through its complex anti-hero, Captain Nemo. As the first fictional book to feature a submarine, written in a style imbued with scientific credibility, it stood out from all previous works.

Test of Time

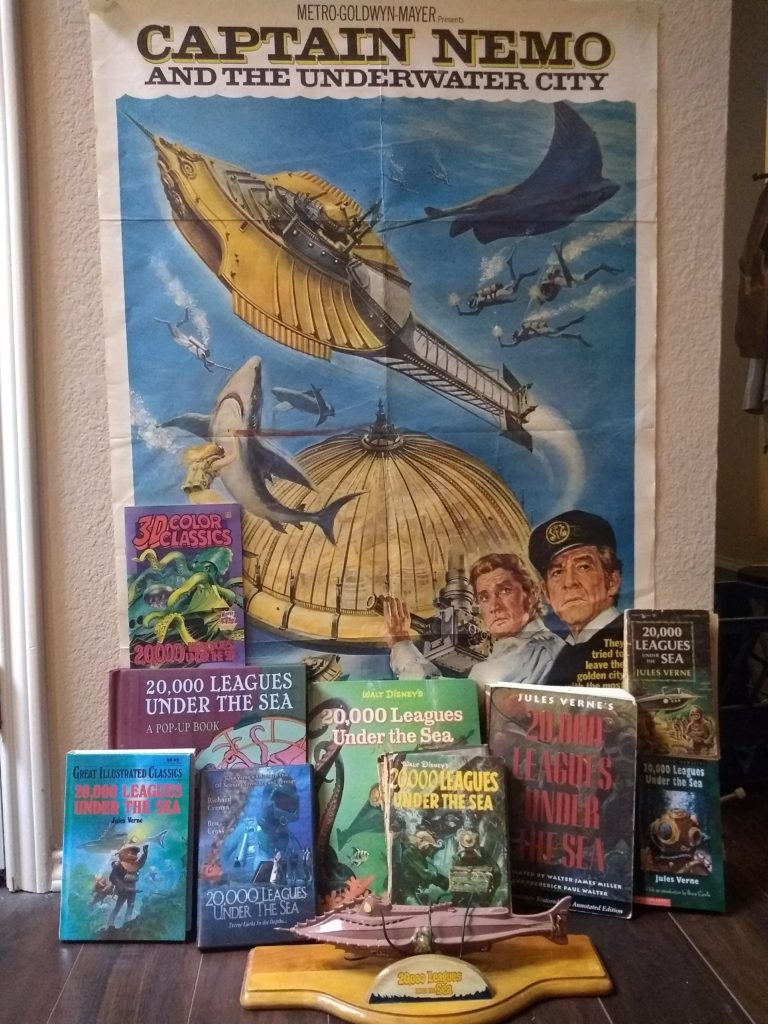

A century and a half after its first publication, 20,000 Leagues is still widely read, with new editions appearing frequently. The novel inspired several films, comic books, video games, and a theme park ride. In 2018, Chicago’s Lookingglass Theatre Company produced a play based on the novel. There’s a Wikipedia entry devoted entirely to adaptations of the work.

Universal Appeal

Everyone can relate to some aspect of the novel. We all admire the unshakable loyalty of Conseil for his master, understand the impulsive and restless Ned Land, sympathize with the dilemma forced on the scientist Pierre Aronnax, and marvel at the unfathomable engineer/pirate Captain Nemo. What reader could remain unmoved while riding along in a fantastic submarine, the Nautilus—part warship, part exploration vessel, and part private yacht—as it cruises from one undersea adventure to the next?

Connections

Verne’s novel contains plenty of allusions to prior works. Captain Nemo’s name (Latin for ‘nobody’) recalled the pseudonym Odysseus used as a ruse with the Cyclops in Homer’s Odyssey. In naming his submarine Nautilus, Verne paid tribute to the American inventor Robert Fulton, who gave that name to his submarine in 1800. The encounter with the giant squid was reminiscent of an octopus scene in Victor Hugo’s Toilers of the Sea. The maelstrom at the end of Verne’s novel honored A Descent into the Maelstrom by Edgar Allan Poe, a writer Verne admired. As already mentioned, this web of connections continued into a vast number of later works, all inspired by 20,000 Leagues.

Relevance

To be relevant, the work must resonate with multiple age groups throughout time. Young people can certainly connect with the adventurous aspects of 20,000 Leagues—the visit to Atlantis, the escape from the ice, the attack on the warship, and the battle with the squid. More mature readers can appreciate Aronnax’s internal struggle between staying aboard for scientific discovery and leaving to escape a madman, as well as the twisted genius of Nemo as he descends into insanity. Even in our age, when nuclear submarines prowl the seas, nothing compares to the Nautilus’ museum, library, and pipe organ. No modern submarine can travel both as deep and as fast as Nemo’s, and the oceans remain almost as mysterious to us as in Verne’s day. Thus, the Nautilus retains its singular fascination for us.

By this standard, 20,000 Leagues has earned its designation as a classic work of fiction. You can check with any literary scholar; you don’t have to take the word of—

Poseidon’s Scribe