I know I said my latest book, the two-story compendium of “Rallying Cry” and “Last Vessel of Atlantis,” would be released today, March 1st. I’ve just been informed that due to circumstances beyond anyone’s control, the book launch will be delayed a few days, perhaps as much as a week.

My many fans around the world, and on other planets, and those in alternate universes (I know you’re out there and that you read my stuff) must be disappointed. I assure you, no one is more distressed about this than I am.

My many fans around the world, and on other planets, and those in alternate universes (I know you’re out there and that you read my stuff) must be disappointed. I assure you, no one is more distressed about this than I am.

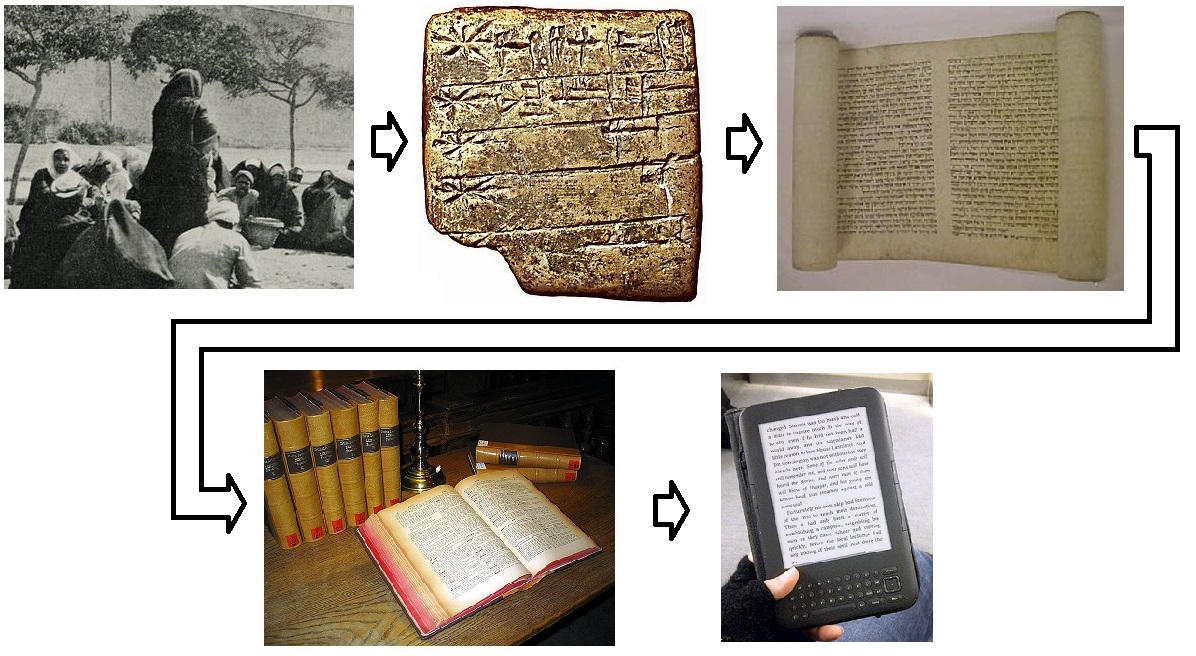

Why the delay? The fact is, publishing an e-book is a complicated business, so I’ve been told. There’s the virtual ink to pour in, the imaginary rollers to align, the invisible type to set. There are gears that turn, levers that snap, boots that kick buckets over, marbles that roll down inclines into chutes, balls that fall into bathtubs, cages that catch mice. It’s very involved.

With all that bewildering complexity, it’s amazing that e-books get published at all, let alone on any kind of schedule.

Meanwhile, you were surfing to the various bookseller websites all day since midnight, searching for my book, ready to put it in your shopping cart and to hit ‘place order.’ And now you have to wait. I know what a frustration this must be.

But think how much worse things are for me. I’ve had to postpone the lavish book launch party, reschedule the reservations on the yacht, tell all the celebrity guests to come back in six days, delay the skywriter service and the fireworks team.

Still, I feel pretty bad about the whole thing. As a service to you, I’ll make some suggestions for fun things to do while you wait, things to take your mind off the anticipation.

1. You could buy and read any of my earlier books.

2. Read them all already? You could read one or more again. They are all good for re-reading since you can pick up subtle and enjoyable nuances you missed on first reading them.

3. You could peruse my earlier blog entries. You’ll find some real gems there.

It’s sad this has happened, but we’ll get through this challenge together, you and me. Think of it as just another of life’s little trials. Are you going to mope around, wallowing in misery? Or are you going to pick yourself up, shake off those blues, rise above your gloom and despair, and manage to make it through the day? Be brave, be resolute, and be patient.

I’ll tell you just as soon as the book is available, believe me. Soon enough your persistence and suffering will be rewarded and you’ll be the happy owner of the latest book by—

Poseidon’s Scribe