Sometimes, you need a certain scene for your story, but you just can’t write it. Has that happened to you? Something about the scene gives you the Blank Screen Blues. Words won’t flow. The idea of writing the scene repels you. You invent excuses not to write.

Sometimes, you need a certain scene for your story, but you just can’t write it. Has that happened to you? Something about the scene gives you the Blank Screen Blues. Words won’t flow. The idea of writing the scene repels you. You invent excuses not to write.

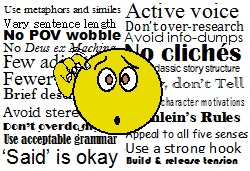

Most likely the problem is one of the following kinds:

1. There’s a ‘story problem’ where the plot isn’t fitting together, or you need a character to do something that character wouldn’t do, or the scene’s setting is wrong.

2. The scene involves a subject or action you find disgusting or abhorrent.

Story Problem

This blog post provides a good five step process for overcoming ‘story problems’ that keep you from writing a scene. Here are the steps in brief, though you should read author Rocky Cole’s more detailed descriptions:

1. Determine why you need the scene.

2. Decide what characters are in the scene and what they want.

3. Decide on a location and time for scene.

4. Figure out how the scene starts and ends.

5. Write the dialogue first, then fill in the rest.

Distasteful Topic

There are certain topics that are difficult to write about. These vary from writer to writer, of course, but can include abuse, alcoholism, death, rape, sex, suicide, violence of other kinds, etc. Some writers find it easier to write about violence to a human than to certain animals.

Sometimes the act depicted in the scene is necessary to the overall story, so you know it’s coming up as you write along. You figure you’ll be okay when you get there, but then comes the day to write that scene and it’s just not happening. You can’t bear to put the words down.

You might be tempted to take the scene offstage. That is, don’t write it, but continue with the following scenes, where the characters recover from or react to an event that happened during an interval between the last scene and this one. You figure that, with enough context, the reader will fill in the gap.

According to the advice offered on this site, that’s a bad idea. The whole idea of fiction, the thing that keeps it interesting to readers, is the notion of characters in conflict. If you take the conflict offstage, you’re keeping your reader from seeing how your protagonist reacts to real difficulties.

I agree with this. Say you can’t seem to write the fight scene where your hero faces the villain. In a way, your own bravery is in question, more so than that of your hero. You need to face your villain, the unwritten scene itself.

Commenters on a Nashville Writers Meetup forum agree too, and recommend just buckling down and using the emotions you’re feeling to write the scene. One quotes novelist Sarah Schulman as saying “If it doesn’t hurt, you aren’t doing it right.”

Along with other blog posts on the subject, this one by author Kelly Heckart emphasizes the need for you to force yourself to do what’s right for the story.

In this forum site, one contributor suggests you might be focusing on your own emotions, your own reaction to a disagreeable act. Instead, concentrate on the reactions and emotions of your characters; that might give enough detachment to allow you to write the scene.

Speaking of detachment, author Linda Govik recommends that you set the whole story aside for awhile, even a year. You might find it easier after that time to write that troublesome scene.

Yet another way to achieve the necessary detachment is offered by the author of this post who recommends thorough research of the disagreeable topic as a way to gain more comfort with the notion of writing about it.

You know what they say: “when the writing gets tough, the tough get writing.” Well, maybe they don’t say it, but I’ve heard it said by—

Poseidon’s Scribe

It’s part of the celebrated What Man Hath Wrought series published by Gypsy Shadow Publishing, and once again you’ll be getting two alternate history stories for the price of one.

It’s part of the celebrated What Man Hath Wrought series published by Gypsy Shadow Publishing, and once again you’ll be getting two alternate history stories for the price of one.