Fantasy fiction writers have an advantage over science fiction writers—no scientist will come along and say the fantasy writer depicted her dragons incorrectly or that she botched a description of werewolves.

But scifi relies on facts about a field that’s frequently upending previous conclusions, so new scientific discoveries can invalidate your fiction at any time.

Still, do those discoveries render the affected novel unreadable? That is, just because your story, written before 2006, discusses the ‘planet’ Pluto, does the body’s new designation as a ‘dwarf planet’ make your novel passé, or so retro as to be unworthy of reading?

The pair writing under the name James S.A. Corey wrote an open letter to NASA about such an occurrence. Their novel Leviathan Wakes portrayed a human population on the asteroid Ceres as being so desperate for water that they obtained it from Saturn’s rings.

In 2015, a NASA mission to Ceres showed that it has plenty of water, easily enough for the millions of people living there in the novel.

Oops.

Does that mean nobody should read Leviathan Wakes or watch The Expanse?

In my opinion, it doesn’t mean that at all. As Corey points out in their letter, there’s a supportive feedback mechanism at work, a mutual admiration society. SciFi writers respect scientists, follow every discovery, and cheer them on. For their part, many scientists were inspired to pursue their passion by science fiction writers.

Many scifi short stories and novels will not endure; their fate will be to gather dust and remain unread. But, that’s not because scientific discoveries rendered them obsolete. It’s because those stories aren’t good fiction.

In other words, classic scifi becomes classic because of its high quality, not because it anticipates new advances in knowledge.

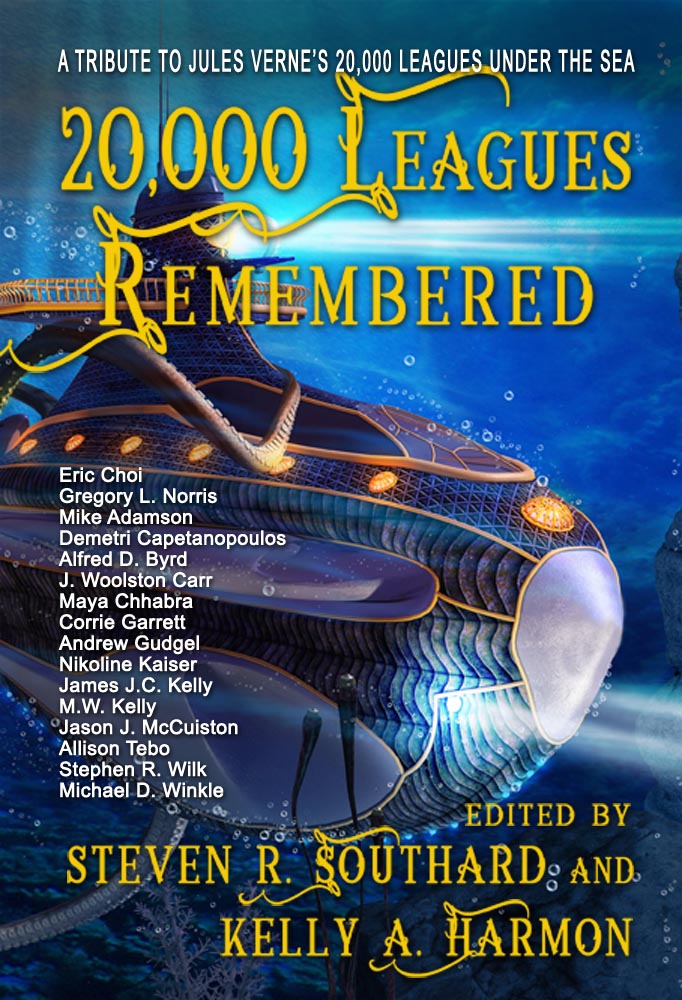

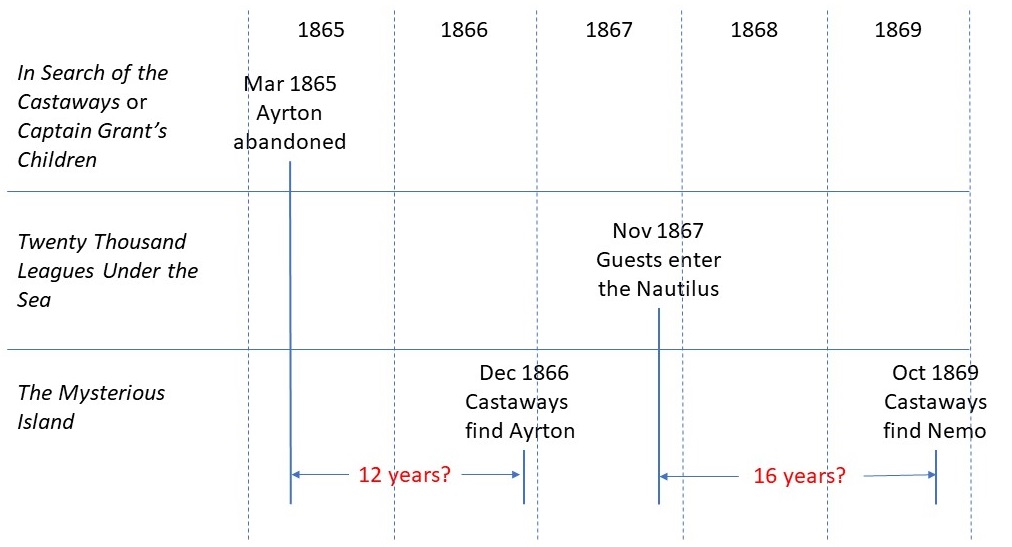

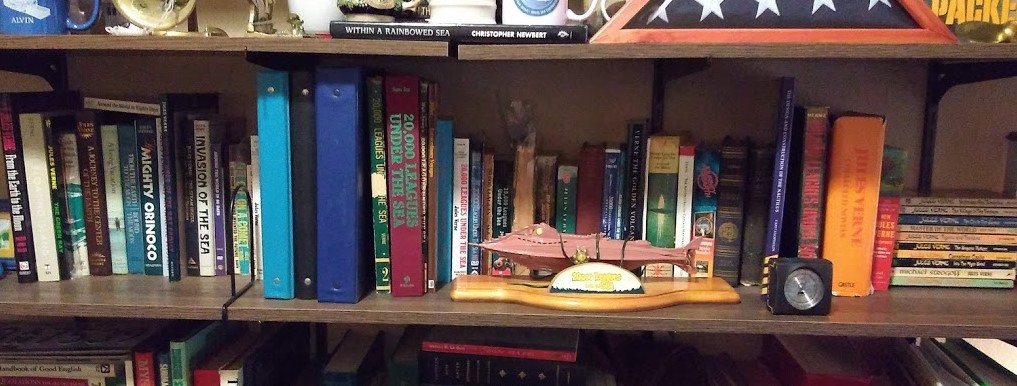

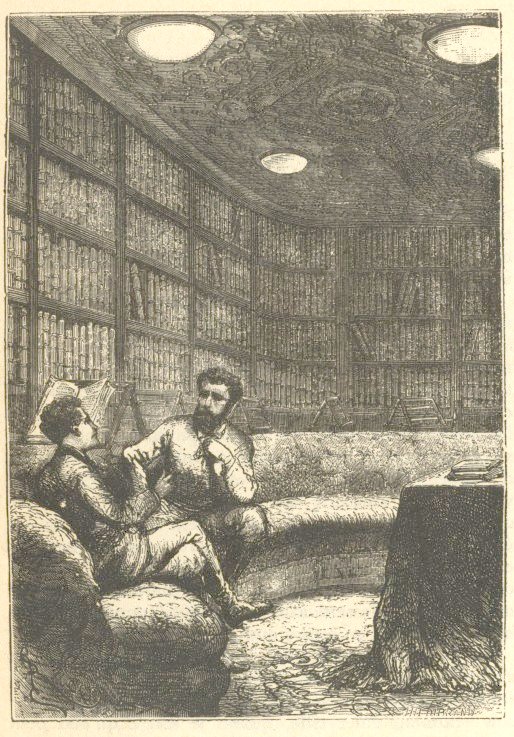

To take my favorite novel as an example, Jules Verne strove to keep Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea as accurate as the known science of 1870 would permit. Today, however, we know:

- A riveted steel submarine could not safely dive as deeply as the Nautilus;

- A sodium/mercury battery would not propel a submarine at fifty knots (without taking up its entire internal volume);

- No spot in the ocean is 16,000 meters deep;

- Sharks do not need to turn upside down just prior to attacking;

…among many other errors. Does that mean you can’t read and enjoy the novel today? Of course you can.

Editors should do their best to provide footnotes or forwards that state where subsequent discoveries have made parts of a fictional work implausible. However, even if they don’t, most readers don’t turn to fiction for the latest scientific facts. Readers understand that scifi authors use the best-known science of their time…and then sometimes stretch that for the sake of a great story.

Science doesn’t ruin scifi. If anything, they reciprocally support each other. In that conclusion, I think James S.A. Corey would agree with—

Poseidon’s Scribe