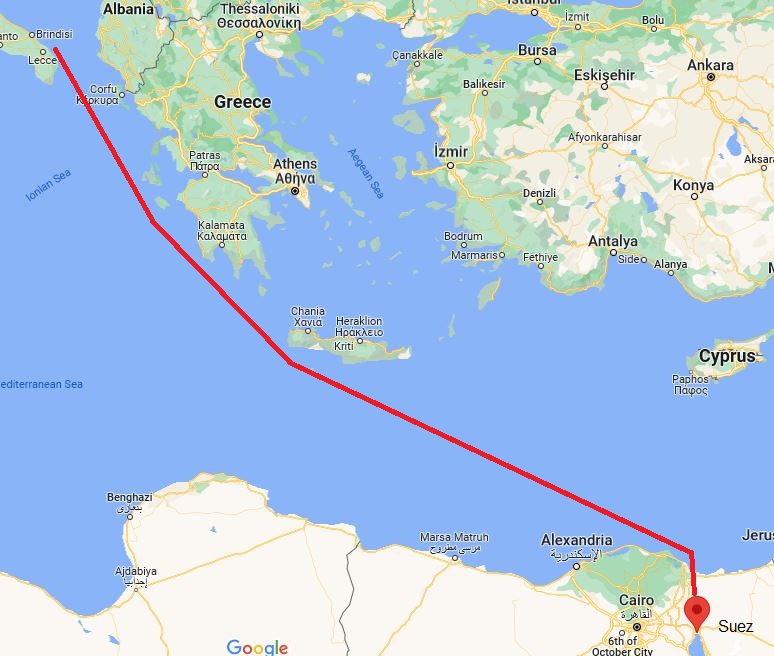

Welcome back to my globe-trotting blog tour. We’re tracing the fictional path of Phileas Fogg as he raced Around the World in Eighty Days, 150 years later. On this date, at 11 am local time, Fogg and his servant reached the city of Suez aboard the steamship Mongolia.

The ship would stay there just four hours to refuel with coal and then cast off to steam toward Bombay. That furnished enough time for Fogg to obtain a visa from the British Consul. He didn’t need the visa to pass through Egypt, but wanted official evidence he’d reached Suez. He’d traveled 2522 miles since leaving London, about 10.3% of the planned distance, but only taken 8.8% of the allotted 80 days.

For Verne’s plot, the refueling stop allowed Detective Fix to see Fogg for the first time, to gain valuable information from Passepartout about Fogg’s intentions, and to firm up his suspicions about Fogg robbing the Bank of England.

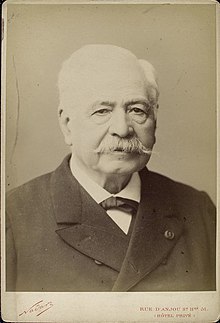

Suez sits at the junction of Africa and Asia, near the southern end of the then-new Suez Canal, completed in 1869. Verne seemed proud of the accomplishment of his countryman, Ferdinand de Lesseps, who masterminded the construction of the canal. Lesseps also gets a mention in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas.

In 1872, Egypt existed as an Ottoman province, known as the Khedivate of Egypt. Isma’il Pasha ruled as the Khedive.

Much has changed in 150 years. They widened the canal to double its capacity. It’s endured wars, the planting and removal of mines, and blockage by a ship running aground.

Long past being a Khedivate, Egypt became a republic with a president, currently Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, and a prime minister, currently Moustafa Madbouly.

Today’s traveler needs far less than 4 days to transit from Brindisi to Suez. You can ride by car to Bari, take a flight to Cairo via Istanbul, then hop a bus to Suez, all in 11 ½ hours.

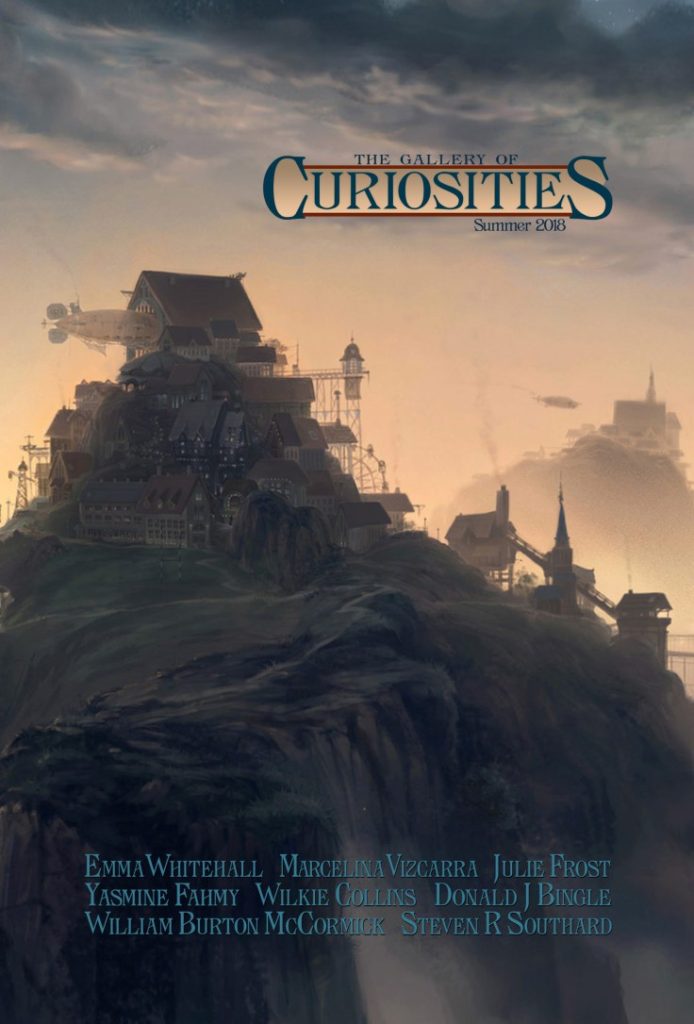

I’ve been pushing my new book, 80 Hours. However, that’s not the only Verne-related piece I’ve written or been associated with. My story “The Steam Elephant” in The Gallery of Curiosities #3 forms an African sequel to Verne’s The Steam House. Think of “A Tale More True” as a clockwork version of Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon. “Rallying Cry” celebrates two Verne novels—The Steam House and Clipper of the Clouds. “The Cometeers” follows From the Earth to the Moon as a sort of sequel. I co-edited the anthology 20,000 Leagues Remembered, with its obvious Verne connection. I also co-edited an upcoming anthology by the North American Jules Verne Society called Extraordinary Visions: Stories Inspired by Jules Verne. Look for news about that here.

If all goes well on our steamship ride, we should reach Bombay (now Mumbai) on October 20, the next entry in this blog trip. Detective Fix may embark aboard the Mongolia as well, along with Fogg, Passepartout, you, and—

Poseidon’s Scribe