Today’s interview features a writer skilled in many forms of the literary art, and all his writing will make you think. He’s written mysteries, thrillers, plays, young adult books, children’s books, science fiction, short stories, novels, and poetry. (I guess it would have been easier to list what he hasn’t written.) Here’s his bio:

Michael Baldwin is a native of Fort Worth, Texas. He holds a BA in Political Science and Master’s degrees in Information Science and Public Administration. Mike is now retired from a career as a library administrator and professor of American Government. He may be a descendant of the Lakota mystic warrior, Crazy Horse, and will be glad to elaborate over a couple of beers. In addition to writing in multiple genres, Mike provides seminars on creativity based on neuroscience.

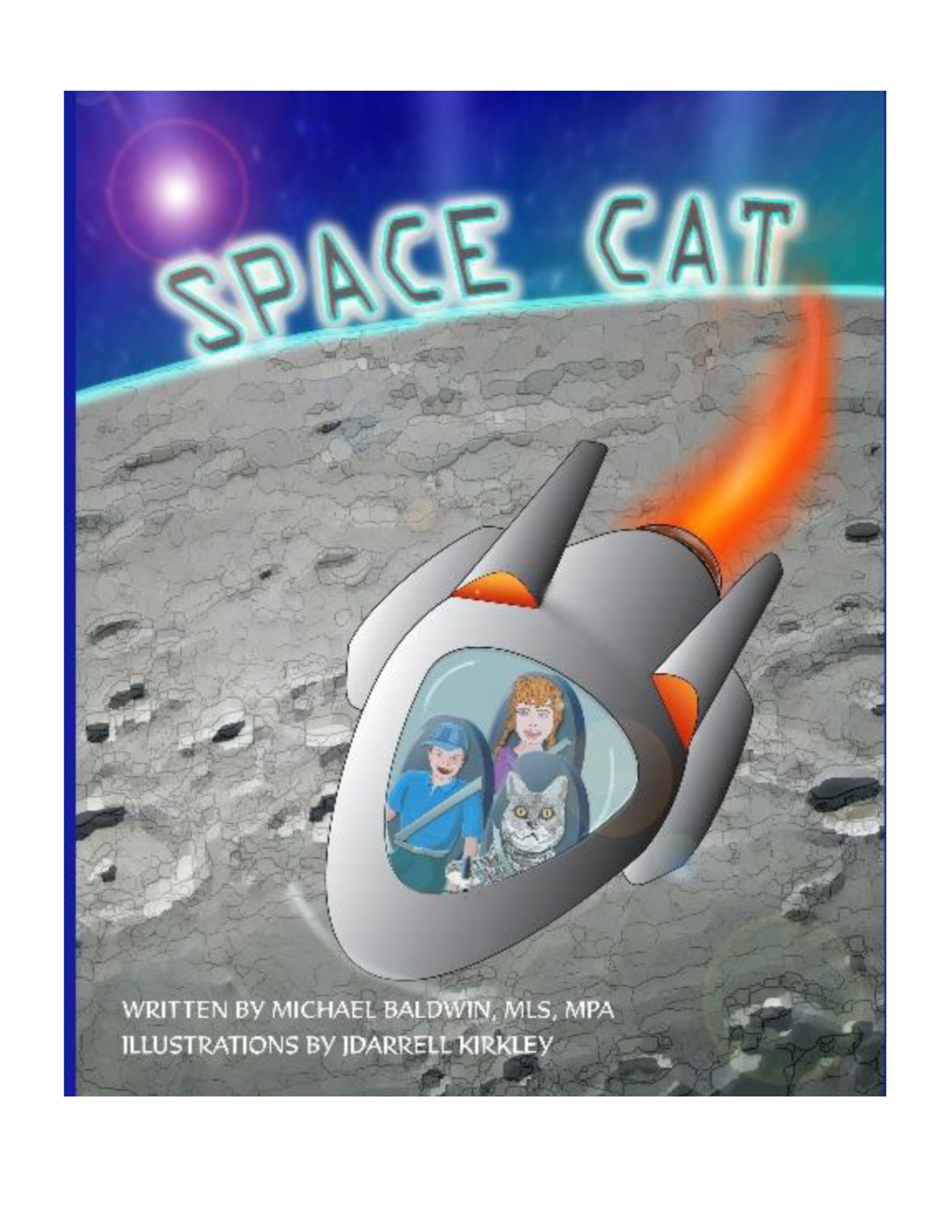

Baldwin has published two adventure novels: Murder Music and Neanderthal Gita. His lifelong interest in science caused him to publish five volumes of science-based science-fiction, the Passing Strange series. Also because of his interest in science, Mike published a children’s science adventure book, Space Cat, which takes kids on a tour of the solar system. Baldwin is also known for his award-winning poetry. He has published five books of poetry, three of which have won awards.

Next, the interview:

Poseidon’s Scribe: How did you get started writing? What prompted you?

Mike Baldwin: I was an avid reader of science fiction in high school. I wanted to try my hand at it and began writing sci-fi short stories at that time and discussing them with friends. I was in the science club at school and built my own Newtonian telescope to do amateur astronomy. Writing about science and exploring ideas thru science fiction just came naturally to me.

P.S.: It’s fascinating that you might be a descendant of Crazy Horse. How much are you willing to elaborate on that without plying you with a couple of beers?

M.B.: As a pre-teen, I found a book in my aunt’s garage titled A Biographical History of North and West Texas. It had an entry about my great grandparents, who migrated to west Texas from Missouri in the late 1800s. It noted that my great grandmother was a Native American woman of Lakota extraction. This was interesting but didn’t mean much to me at the time. As an adult, however, I became interested in my Native American heritage and happened to read Larry McMurtry’s biography of Crazy Horse. CH had a daughter who disappeared as a teenager after Crazy Horse was assassinated. It was rumored she had married a white man and moved south. That included the time period my great grandparents migrated to Texas. So, I claim her and Crazy Horse as my ancestors even tho it can’t be proven definitively. I like to think I received some of Crazy Horse’s mystic qualities of mind.

P.S.: Who are some of your influences? What are a few of your favorite books?

M.B.: As I said, I read science and science-fiction extensively as a boy. I went by bus to the central library almost every Saturday and raided their sci-fi section. Asimov, Heinlein, A.E. Van Vogt, Clifford Simak, Andre Norton, Ray Bradbury, Arthur Clark, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and Jules Verne, were among my favorites, but I read them all voraciously. I couldn’t afford to buy the sci-fi magazines, so the library was my treasure place. Little wonder that I later became a librarian.

But I also read real science adventure books avidly. Beebe’s descents into the oceans, Frank Buck’s tales of the African jungles, and many more. As a teen I really liked the sci-fi of E.E. Smith because it was highly imaginative, far reaching in its scope, and had wonderful aliens as well as human heroes (the lensmen). But when I tried to read Smith’s books as an adult, I found them disappointing. The teen mind must be much more forgiving of style and literary quality.

A non-fiction science book I enjoyed as a teen was Worlds In Collision by Emmanuel Velikovsky, which theorized that the Earth and solar system might have been affected by a rogue planet invading the solar system in prehistoric times. It was full of footnotes, including citing Ibid frequently. I had never seen Ibid before and assumed it was a book rather than just designating the same work as previously cited. I asked the school librarian if she had a copy of the Ibid. She had a good laugh before explaining.

P.S.: Maybe the librarian laughed, but she must also have been impressed. You write a wide variety of things for different audiences. Among your adventure novels, plays, science fiction, children’s books, and poetry, do you have a favorite?

M.B.: I really don’t have a favorite except whichever one I am currently working on. I like them all and am proud of them all. I think they all turned out well. Although I enjoy writing in several genres, the common thread is ideas. All my books are based on ideas I get from my own extensive reading and from the universal subconscious, which is available to anyone. All my books explore one or several major ideas, but also bring in social, political, religious, scientific, and other topics as they fit into the plot (or in the case of poetry, the concept of the poem).

P.S.: Tell us about your Passing Strange series. Are there common threads among the five volumes? Can readers tackle them in any order? Do you plan to write more in this series?

M.B.: When I published the first volume, Passing Strange, I didn’t plan to write a series, but the ideas just kept coming, so the other volumes insisted on being written. There are no continuing or connected stories in the series except there are several stories scattered among them with the character, Zbub. The first story of Zbub has him as a sort of strange, creepy character who is not the real focus of the story. But Zbub wouldn’t let go of my neurons, so I kept writing stories with him as a character, usually just as a means of inciting the action. His character kept becoming more complex and interesting, so I kept writing more of his stories. I think readers will find him likeable and amusing as a trickster who really shakes things up.

After five volumes of Passing Strange stories, I’m taking a pause and am thinking of sequels to Murder Music and Neanderthal Gita which interact with each other. But I am constantly making notes of ideas for more sci-fi stories, so maybe there will be a 6th volume of Passing Strange and probably more Zbub.

P.S.: Your novel Murder Music contains many strange and delightful aspects, but at one level, it’s a mystery thriller featuring a young woman and her haunted violin. Tell us about Missy McKean—who she is, her personality, and whether someone in real life inspired this character.

M.B.: Yes, as a matter of fact, Missy was inspired by my daughter and her cousin as teens. They were both highly intelligent wild girls who were always getting into some sort of mischief. One was a fine musician and scholar, the other highly scientifically minded who became a doctor and psychiatrist. I had been thinking about writing a novel about musicians for some time because I had been an amateur musician and interested in classical and jazz all my life. But I decided it needed to be an adventure and preferably a mystery that departs from the usual, worn out tropes of the standard mystery. I also had many ideas about unusual mental capabilities I wanted to explore with the book. Then I thought I might as well throw in a metaphysical aspect with the haunted violin. By the way, much of the information about the Guarnerius violin and its owners is historically accurate. Also, the information about Dillon Moonbear being conceived in orbit around the moon and born to a bear was scientifically and historically feasible.

P.S.: It’s fascinating to imagine the implications of a tribe of Neanderthals still existing, hidden, today. Readers can enjoy your approach to that idea in Neanderthal Gita. What prompted you to write this novel?

M.B.: I’ve always been interested in prehistory. My dad studied historical geology in college and often took me out looking for fossils and talking about dinosaurs and early man. Like most people, I thought Neanderthals were more primitive than cro-magnon people (us) who succeeded them. But modern scientific techniques began to find that the Neanderthal were much more complex than we had thought. They had a larger brain capacity than us. They were much more muscular than us but weren’t knuckle draggers. So they may have been superior to us in both intelligence and physical capabilities. I found that there were few novels about Neanderthals, and none that made use of the latest information about them. So I researched Neanderthals extensively and wrote about them imaginatively. I invented a culture for them that was true to what we now know of them. The only liberties I took were to make a tribe of them survive into modern times and have mental telepathy (that extra brain capacity).

P.S.: What are the easiest, and the most difficult, aspects of writing for you?

M.B.: Many writers complain of writer’s block, of fear of the blank page. I’ve never had that problem. In fact, I get more ideas than I’m able to deal with. If I forget to jot down an idea, it may disappear into my forgetter, which is stronger than my rememberer. My main problem is that every time I return to a story or poem I’ve written, even those I consider finished, I want to tinker with it and make changes. All writers do that to an extent, but they should realize that when they look at it again, they are a different person. Their brain has changed significantly, so they (and I) may have a completely different perspective on it. So I have to struggle with myself to let it go.

P.S.: You’ve written several books of poetry, and some have won awards. Congratulations on winning the Edward Eakin Poetry Book Award and the Morris Memorial Chapbook Award. What sort of poetry do you write? Are there common themes or other similarities that mark your poems?

M.B.: Ah, now you’ve hit on a sore subject for me. Most of my poetry is about ideas, as I also said about my fiction. Ideas are or were a major force in poetry, from Donne and Shakespeare to Whitman, Dickenson, Eliot, Pound, and Frost. But in the last ten to fifteen years, poetry has become more interior, more personal, more narcissistic. So I’ve had more trouble getting my poetry accepted for publication in journals, which are mostly managed by young poets of this new poetic trend. This change has been noticed and criticized by several major poetry critics in articles and books, so it’s not just my feeling of sour grapes.

I’ve written poetry based on science (Counting Backward From Infinity), on spirituality (The Quantum Uncertainty of Love), on nature (The Sublime Landscape and Beyond), on Asian Poetry (Birds, Beasts, and Blossoms), on my personal life experiences (Lone Star Heart) and on a mixture of the above (Scapes).

P.S.: Sorry, I didn’t mean to hit a nerve. Let’s move on. Your children’s book, Space Cat, is a fun and educational romp through the solar system. It’s such a departure from your other books—how did you come to write it?

M.B.: I became interested in doing a children’s book when my grandsons started to read. I greatly enjoyed reading to and with them. Also, that was about the time the Hubble Telescope began producing such gorgeous images of space. I had been an amateur astronomer and interested in science all my life, so a children’s space science book was what came naturally. I decided it needed to provide an exciting adventure as well as scientific information in order to hold kids’ attention and spark their imagination.

P.S.: What is your current work in progress? Would you mind telling us a little about it?

M.B.: I just finished a novel (still tinkering with it of course) for which I’m seeking a publisher. It is a historical literary novel that also has aspects of romance and adventure. It involves four jazz musicians who are in and out of love with each other between 1985 and 2002. They have small adventures and emotional crises at home but also participate in larger events such as the 911 tragedy, the war in the Balkans, and the Afghanistan War. Music, poetry, and romance are the primary themes. Some of the characters from Murder Music and Neanderthal Gita also figure in the story, but not as major characters.

I’m also working on two books of poetry: one about climate change and one about politics and social problems.

Poseidon’s Scribe: What advice can you offer aspiring writers?

Mike Baldwin: Forget about it unless you are a masochist! If you are not completely serious about writing and/or don’t read much, don’t bother to try to become a writer. Starting as a writer is very hard and a long, draining struggle. You should have many years of reading behind you as a basis for knowing what good writing consists of. You have to discipline yourself to sit and write almost every day. Most of what you write the first couple of years will be crap and must be rejected. But as you gain experience, your brain will become more efficient at writing and presenting ideas to you. Even if you become a proficient writer, however, you will find you can’t make a living at it. There is too much competition now because computer technology made it much easier for anyone to write. But the publishing industry has changed to become much more demanding and less supportive for the writer than it was in previous times. Self-publishing makes getting a book before the public easy, but you have to promote it massively and relentlessly to develop a readership and get paid for your stories. So don’t waste your time or torture yourself writing. You stand a better chance becoming a professional athlete than a best-selling author. Just buy my books, kick back, and enjoy a brilliant, enthralling, mind-bending story.

Poseidon’s Scribe: Thank you, Mike. I agree with and endorse the idea of buying your books. Perhaps would-be writers should embrace the idea of writing for enjoyment rather than making a living from their words.

Readers may find out more about Mike Baldwin at his website, on Facebook, Linked-In, and on Amazon.