Search on the internet for “seasteads” and you’ll soon see mentions of billionaires and libertarians. Why is that? Are seasteads only for people in those small groups? Let’s explore the question.

Billionaires

I believe billionaires get mentioned with seasteads for two reasons: (1) Seasteads cost much more to build than houses on land, and (2) Billionaires often chafe at paying high taxes in their home country and long to escape to a low-tax country, of which few exist.

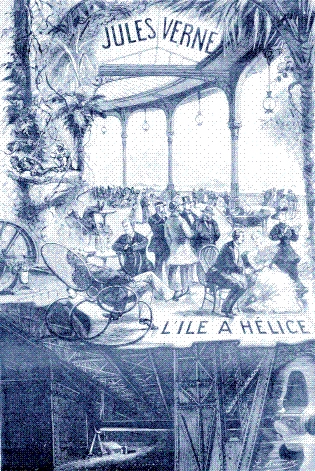

Among the earliest fictional examples of seasteads was Standard Island, a floating, mobile seastead in Propeller Island (or L’Île à hélice) by Jules Verne (1895). American millionaires built it.

In real life, seasteads might not require billionaires at all. Settlers might construct a small one without spending vast sums. They might build on an existing, abandoned platform, as with the Principality of Sealand. Crowdfunding might present another way to pay for a seastead’s construction, with perks of citizenship offered in exchange for contributions.

Libertarians

Seasteading often gets associated with libertarianism because adherents to that political philosophy see few, if any, land nations living up to libertarian principles. Their efforts to influence one or more existing countries to adopt libertarianism have failed. Some now believe the only way to live in a libertarian country is to create a new one.

However, nothing about the seastead concept requires a libertarian governing philosophy. If you build a seastead, declare it a country, and somehow get it recognized as such, you could set up any form of government you please.

The Seastead Chronicles

In my book, The Seastead Chronicles, a brash billionaire builds a seastead and declares ownership of a sector of the ocean. I don’t state the type of government on that seastead, so readers may imagine what they wish.

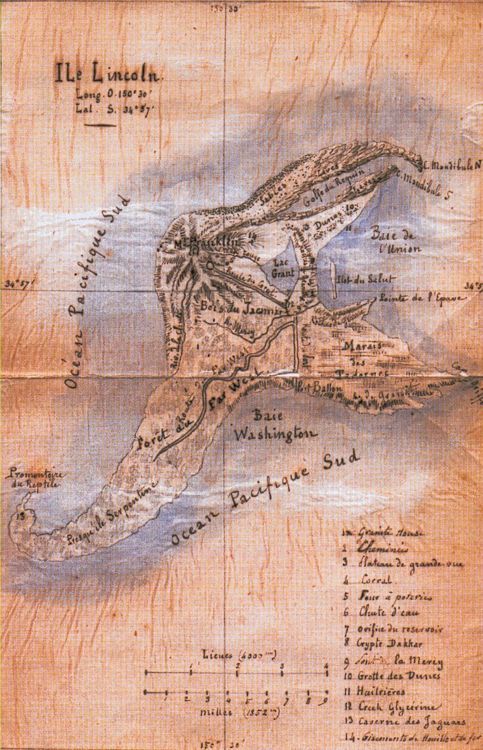

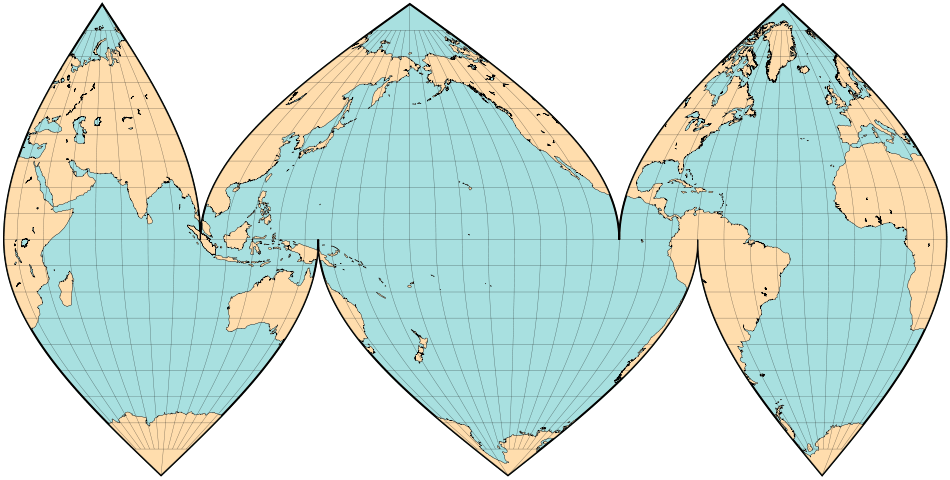

The fate of that seastead initiates a “gold rush” for oceanic oil and minerals, boom, and other seasteads get established. Most of these locate near known ocean bottom resources to take advantage of seabed mining. They divide the oceans into nations, called aquastates, which other nations and the U.N. recognize. As with land nations, territorial disputes arise, some leading to war. A few aquastates go bankrupt and get absorbed.

Only one story in The Seastead Chronicles mentions the building of a seastead and I gloss over its funding. My stories depict seasteads as existing structures, since my aim is to imagine the effect on people of living at sea. Billionaires might have been involved in funding some of the seasteads, but others might have been built by corporations or crowdfunding.

As for governing systems, they run the gamut. I assumed people would flee their home countries and establish the government they dreamed of at sea. Given a fresh start, they’d set up their own planned utopias. A few might lean libertarian, or start off that way, but I imagined others as solarpunk, anarchic, monarchic, military oligarchic, cooperatively leaderless self-governing, etc.

Up to You

If seastead cities and their aquastates got established in real life, how do you think it would happen? Would only the super-wealthy fund their construction? Would libertarianism dominate their governing philosophies? You might enjoy letting your imagination conjure cities and countries at sea. You could come up with ideas even more outlandish (pun intended) than those of—

Poseidon’s Scribe