Humanity just doesn’t go in for long-term projects anymore. The fire at Notre-Dame de Paris cathedral this past Monday got me thinking about projects that extend beyond a single human lifetime.

The French are determined to repair their beloved medieval church. Estimates of the duration of repairs range from five to twenty years or more. Those timeframes would have astounded the laborers who built it. They needed 182 years to finish the cathedral.

That sort of project duration was typical for cathedrals of the period. It seems we’re no longer accustomed to ‘generation projects.’ We’re used to completing large structures (buildings, dams, tunnels, bridges, etc.) in spans of less than thirty years.

Imagine what it took to build something that required centuries. The original planners, designers, and workers knew they’d never see the completed work. The designers passed on their plans to others, and hoped the enthusiasm for the project would carry through. Laborers in the middle years worked on a project they didn’t originate and knew they’d never finish. Only the final generation of workers lived to enjoy the project’s culmination.

As an engineer with some program management experience, I marvel at such long-term projects. As a fiction writer, I try to understand the motivation behind them. How did builders sustain the guiding vision generation after generation? Let’s explore some historical generation projects, proceeding from most recent to oldest.

Temple Expiatori de la Sagrada Família. When finished, this will be a Roman Catholic Church in Barcelona, Spain. Begun in 1882, the project encountered difficulties including war and fire that delayed it, though it’s due to complete in 2026, fully 144 years after its start.

Saint Basil’s Cathedral. Begun in 1555 in Moscow, this church took about 123 years to complete in 1678.

St. Peter’s Basilica. This Italian Renaissance church stands in Vatican City. Construction began in 1506 and ended in 1626, 120 years later. Construction delays included difficulties with its immense dome and a succession of architects redesigning it, among them Michelangelo and Raphael.

Leaning Tower of Pisa. This cathedral bell tower in Pisa, Italy was doomed from the start of its construction in 1173, as it stood on unstable subsoil and started to lean. The difficulty of compensating for that lean was only one of the factors delaying its construction. War with other Italian city-states was another. Despite these setbacks, builders completed the project after 199 years, in 1372.

Notre-Dame de Paris. The fire on April 15 reminded us all that all of humanity’s creations are subject to damage, and fire is perhaps the biggest threat to wooden structures. Construction of this medieval Catholic Cathedral began in 1163, and was mostly done by 1260, but modifications continued until 1345, a total of 182 years.

Angkor Wat. According to one source, the building of Angkor Wat (in what is now Cambodia) began in 802 in the Khmer Empire and completed in 1220, taking 418 years. It started as a Hindu temple and later became a Buddhist one.

Temple of Kukulcan. Also called El Castillo, this Mayan step pyramid, built as a temple to the god Kukulcan, stands in the ancient city of Chichen Itza in what is now Mexico. Construction started in the year 600 and continued in phases to 1000, a duration of 400 years.

Great Wall of China . On my list of generation projects, the Great Wall boasts the longest duration. One site dates its start as 400 B.C. and its completion as 1600 A.D., or two millennia. Ordered by the emperors of various dynasties including the Qin, Han, Qi, Sui, and Ming, the guiding vision seems to have been protection against raiders from the northern steppes.

Stonehenge. Now we come to the oldest generation project on my list, a Neolithic structure in England begun around 3100 B.C. and completed around 1600 B.C. The builders left no records, and the structure’s purpose is unknown. Theories include a burial site, an astronomical observatory, ancestral worship, a symbol of peace and unity, and a place of healing.

From the above list, we can see that, with the exception of the Great Wall and possibly Stonehenge, religion provides a strong motivation for embarking on and sustaining a long-term project. Also, it’s generally true that these projects took a lot longer than originally planned, encountering various disruptions and delays along the way.

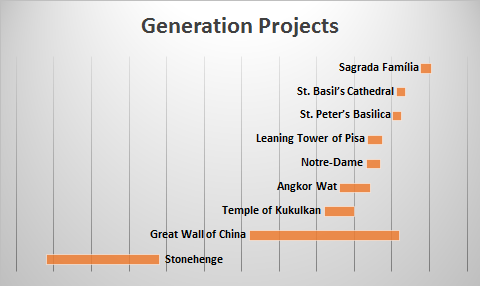

If we graph the timeline of these generation projects, it’s clear the timeframes are shortening, likely a result of advancing construction techniques and laborsaving machinery.

Given the faster pace of modern construction, have we lost the ability to plan and accomplish long-term projects? Could we sustain the enthusiasm of a building project over centuries, as our ancestors did?

If we desire to build megastructures on a planetary or stellar scale someday, things such as terraformed planets, Shellworlds, Niven Rings, Dyson Spheres, and others, it’s likely we’ll have to reacquire the multi-generational mindset of those who came before us.

To sustain a project of that type we’d need a motivating spirit, a shared vision as powerful as the ones (like religion or protection) that inspired our predecessors.

Alternatively, we could work on extending the human lifespan. A career length of two thousand years, sufficient to oversee the entirety of the Great Wall, seems like a fine notion to—

Poseidon’s Scribe