Have you ever enjoyed an author’s books, then found out something disturbing about that author? Did the revelation spoil your appreciation of the books?

I suspect we’ve all been let down by a hero. Perhaps a favorite actor, athlete, politician, or artist did something unsavory, and that detracted from your experience of their work. It stains their reputation, at least for you. You’re no longer able to separate performer from performance.

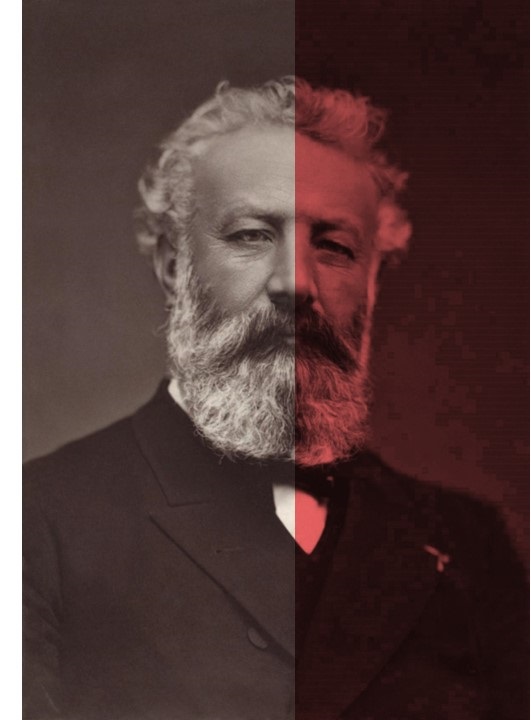

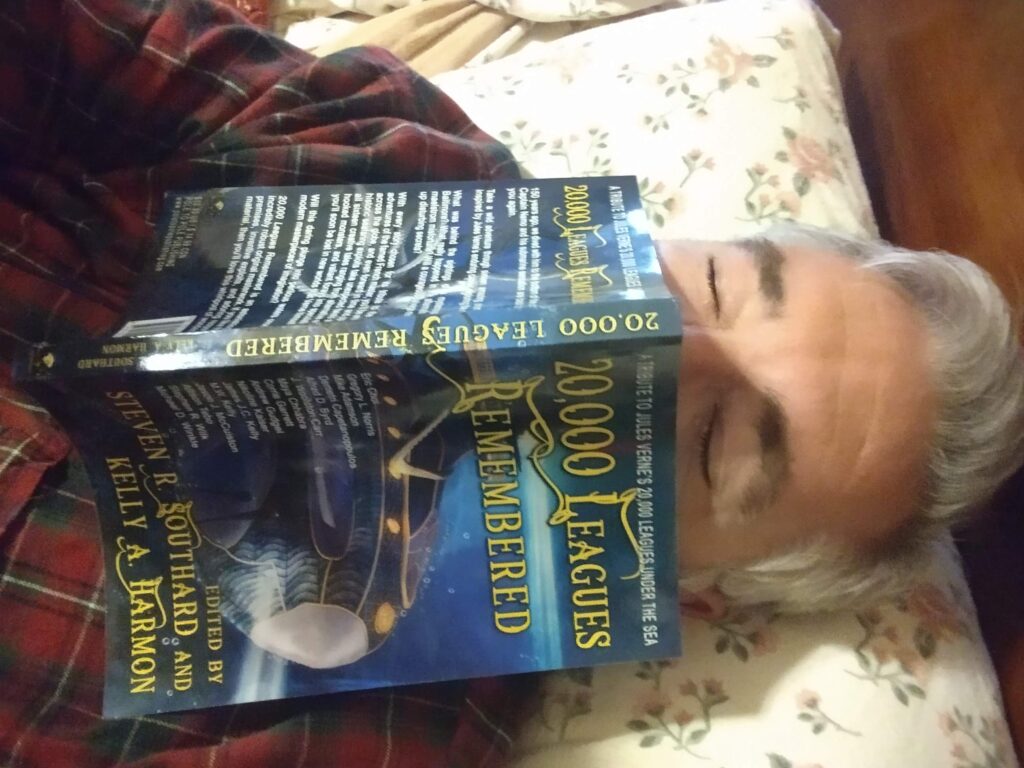

The works of Jules Verne, my favorite author, come across today as antisemitic, racist, and sexist. His anti-Jewish sentiment is evident in both Hector Servadac (also published as Off on a Comet) and The Carpathian Castle where he depicts Jewish characters in a bad light. He includes characters of color in many novels, but never as the hero and often in stereotyped ways—servants or cooks—subordinate to the white hero. At least he includes them, unlike those of the female gender, who rarely appear at all in his works.

I could excuse these ‘isms’ and rationalize my continued reading of his works, by observing that this 19th Century French author reflected the prevailing biases, prejudices, and privileges of his time. I could say it’s unfair to impose my modern standards on a man no longer around to defend himself.

But I believe that lets both of us—me and Verne—off the hook too easily.

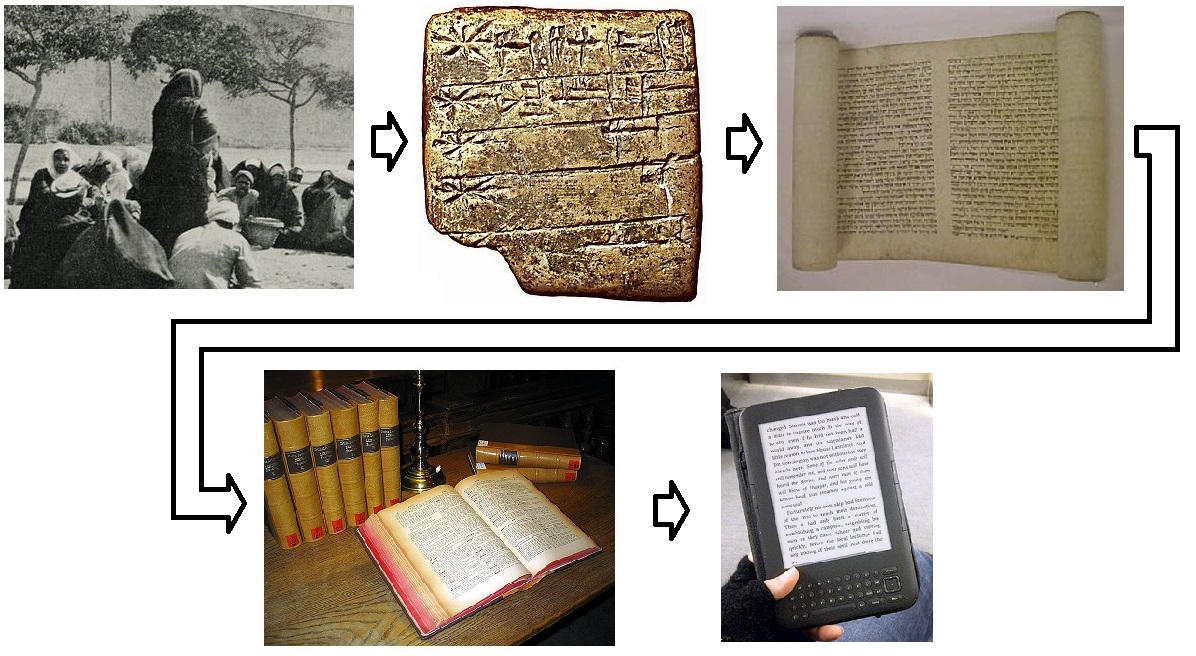

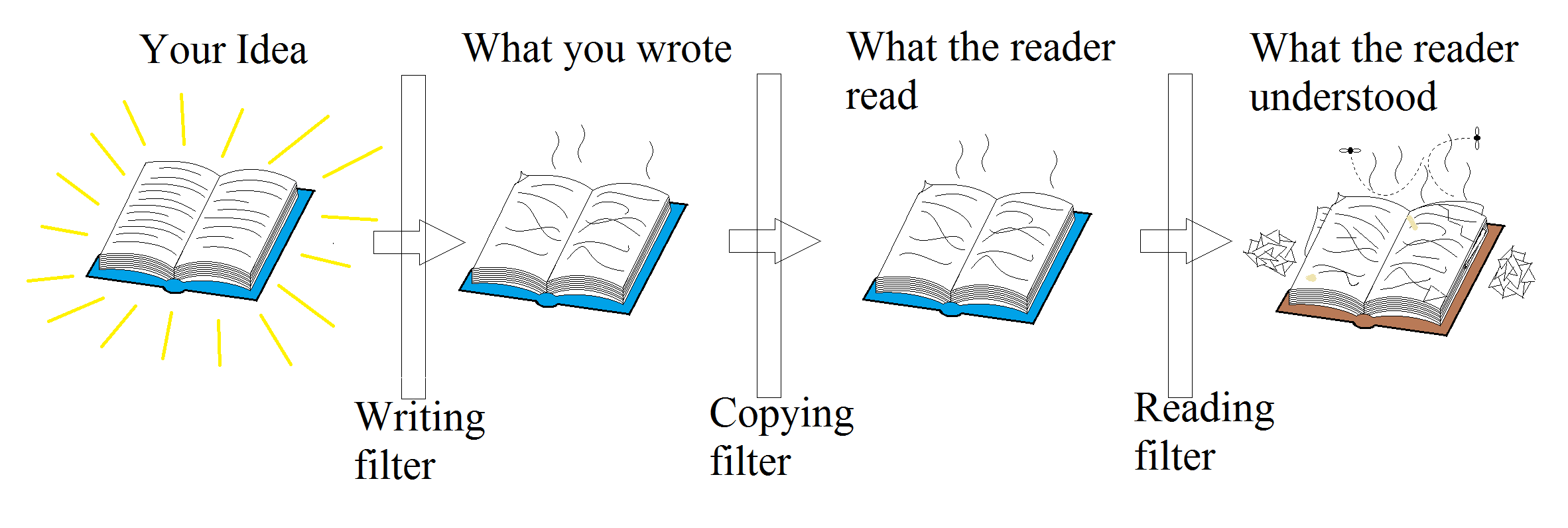

Consider that reading represents a form of communication, and that it involves a sender (the writer) and a receiver (the reader—you). Your appreciation of the written work occurs at that interface where you interact with the text.

Therefore, you bear a share of responsibility here and you can’t shrug it off. Your love for or hatred of the book is an individual reaction you own, an experience you share only with the writer, whether that person is alive or dead.

All written material to which we have access was written by humans. All humans suffer from faults, frailties, and weaknesses of some kind. You lack the option of reading books written by angels. Sorry about that.

Knowing this, you face a choice. You might refuse to discover anything about the author. That spares you from any knowledge of skeletons lurking in their closets. But it sets you up for profound disappointment if you ever find out your favorite author slipped off the mental pedestal you erected and fell short of your moral standards in some way.

On the other hand, you can read with full understanding that you consume text produced by a flawed author—a human. You can research the author and discover some distasteful truths, and read the work anyway.

Here’s where I stand with Verne. I can’t claim ignorance of his backwards attitudes. If I choose to enjoy his novels, I must decide that the good outweighs the bad. Further, I must recognize this as an individual choice. Other readers make their own choices.

I like to read Verne’s novels, most of them. I don’t excuse his faults, don’t condone his biases. I wince at his stereotypes and cringe at the prejudiced opinions. I don’t idolize him. I’ve decided, for me, his strengths outweigh his weaknesses.

You face similar decisions whenever you read anything. Does the good exceed the bad? Do the delights of the book surpass the poor behavior or faulty value system of the writer?

When you read a work, only you can weigh good against bad. Nobody else can do it for you, not reviewers, critics, or even—

Poseidon’s Scribe

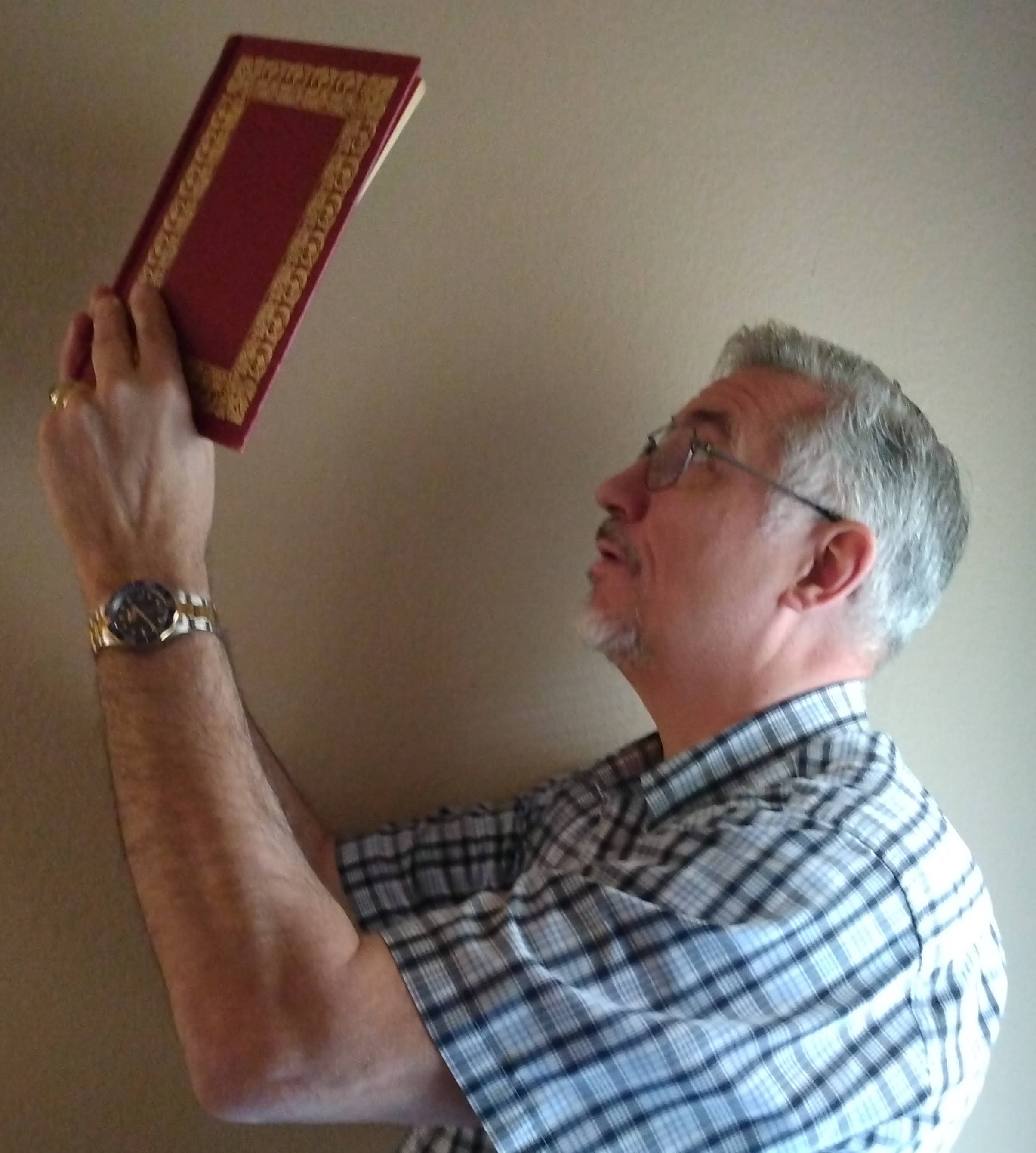

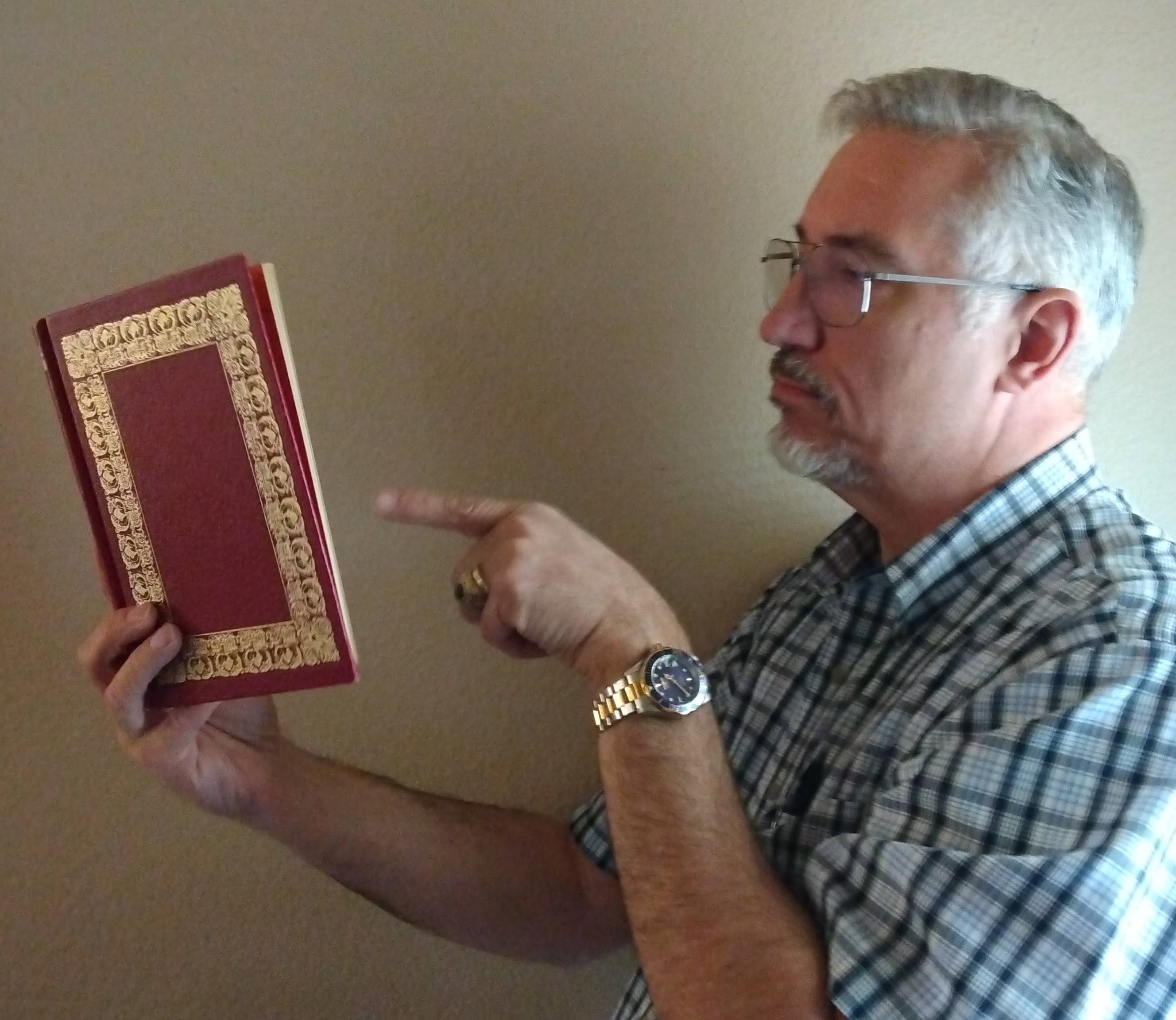

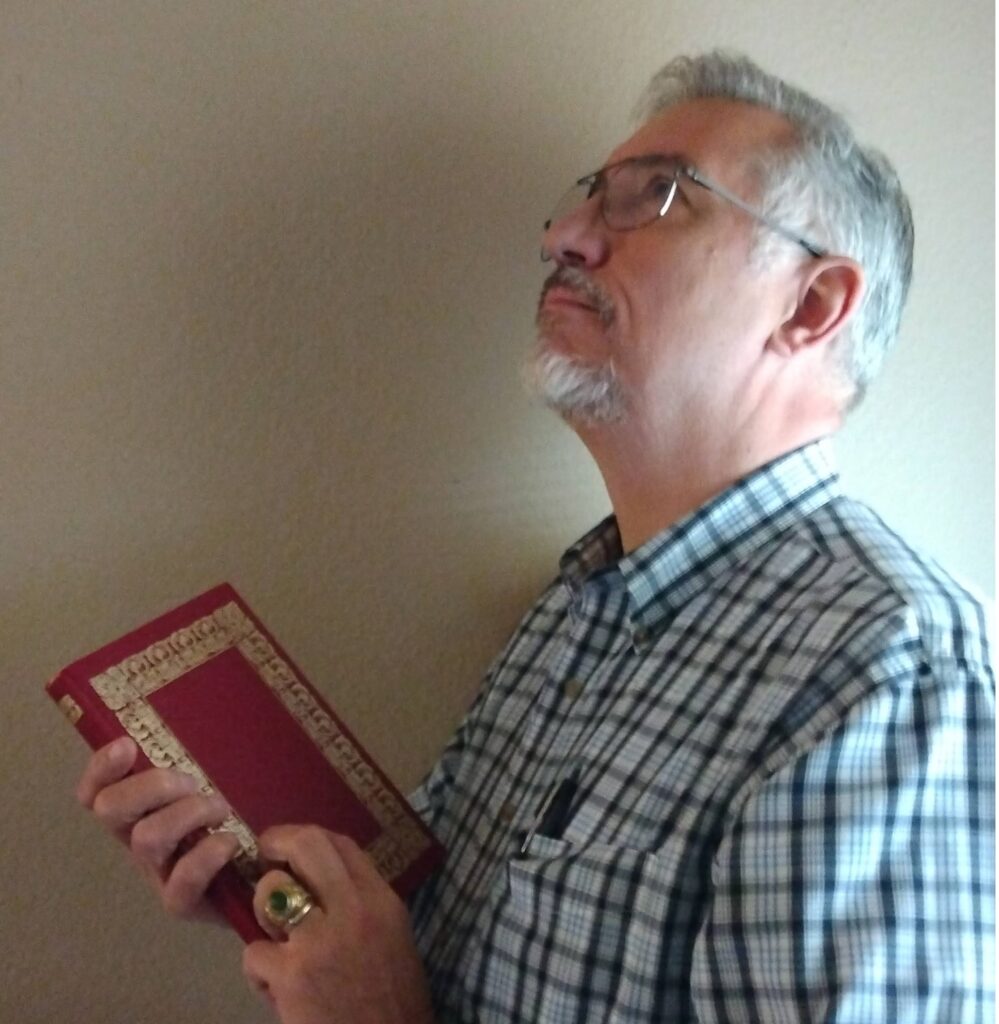

The process is usually not as bad as the way I’ve dramatized it in the accompanying image. Still, it’s a less efficient transmission method than mental telepathy would likely be.

The process is usually not as bad as the way I’ve dramatized it in the accompanying image. Still, it’s a less efficient transmission method than mental telepathy would likely be.