A potential Wikipedia entry:

Homo Scriptor

The writing human (Homo scriptor) is a subspecies of Homo sapiens, differing from H. sapiens only in its highly developed skill in writing. Though most humans write to some extent, Homo scriptor writes as an obsession, often to the exclusion of other activities.

Etymology

The genus Homo refers to human and the subspecies designation of scriptor (from Latin) refers to a person who writes.

Taxonomy and Phylogeny

Homo scriptor is a subspecies of Homo sapiens, member of the tribe Homanini, the family Hominidae, the order of primates, in the class Mammalia. H. scriptor has not yet split off from H. sapiens, and mating between the two can occur, but scientists believe sympatric speciation (the splitting apart into separate species) may be underway.

Description and Characteristics

In appearance, H. scriptor is indistinguishable from H. sapiens. Specimens of H. scriptor are present in the same genders and races as H. sapiens, in approximately the same proportions. Behavior is the only distinguishing indicator between the two.

Distribution and Habitat

Scientists estimate the world population of H. scriptor at around 400,000, perhaps 1 in every 20,000 humans. Homo scriptor has accompanied H. sapiens to every continent. They cluster in cities, as does H. sapiens. They occupy the same types of dwellings, though H. scriptor insists on one quiet space within the abode for solitude, writing, and the storage of books.

Behavior

Diet

H. scriptor eats the same foods as H. sapiens, but prefers to spend less time in obtaining, preparing, and consuming the food, to leave more time for writing.

Locomotion

H. scriptor walks in the same bipedal manner as H. sapiens, but less often, since writing is a sedentary activity.

Reproduction and Parenting

H. scriptor mates in the same manner as H. sapiens. However, for H. scriptor, the sexual act provides an additional benefit—research for a future book.

Any combination of H. sapiens and H. scriptor parents may result in either H. sapiens or H. scriptor offspring. Scientists have not yet identified the genetic markers for H. scriptor.

Social Structures

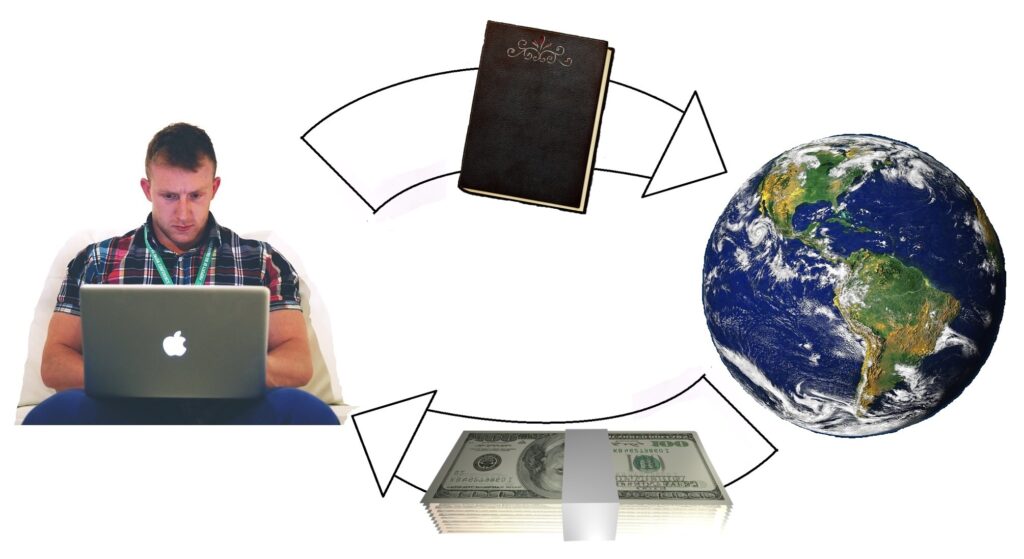

The main and subspecies share a mutualistic symbiotic relationship. H. sapiens seeks and pays for the product (books) of H. scriptor’s work. H. scriptor writes books for H. sapiens’ enjoyment and receives payment in return. With both symbionts achieving benefits, this relationship seems likely to continue. The two freely associate in complex social structures, though H. scriptor may seem aloof and isolated.

Communication

Since the advent of written language in the late 4th millennium BCE, H. scriptor has exceeded H. sapiens in this activity, both in quality and quantity. On the other hand, H. sapiens surpasses H. scriptor in nearly all other human activities. The written language prowess of H. scriptor does not typically extend to other forms of communication. For example, H. scriptor may not speak any better than H. sapiens, and when the writer subspecies does speak, the topic is often about writing.

Cultural Significance

With the exception of non-written language arts, such as music, sculpture, and painting, Homo scriptor provides culture for Homo sapiens. All novels, short stories, plays, song lyrics, newspapers, motion picture scripts, television scripts, and Wikipedia entries were written by members of H. scriptor for the enjoyment of H. sapiens. Due to the symbiotic relationship, the writer subspecies rarely writes about itself, but more often about the main species.

See also

Human

Subspecies

Symbiosis

Writer

I’m sure you’ll agree, that’s an accurate and informative article. There’s no way Wikipedia would turn down this submission from—

Poseidon’s Scribe